Trump's Navy: A Look at the Future US Navy

By Edward Lundquist

It’s still too early to know for certain what the new administration will do about building up the U.S. Navy, as the numbers are a moving target. But with President Trump’s recent pledge to add $54 billion to defense spending, it’s a safe bet to make that the fleet will grow.

So let’s start with the numbers. There are different ways to count the fleet size, including whether or not you count auxiliaries, but let’s use this number as the baseline: There are 274 ships in the U.S. Navy now. The current objective is to increase the fleet size to 308, according to the approved 30-year shipbuilding plan and the FYDP, or Five Year Defense Plan.

Every navy wishes it had more ships, people and stuff. Strategic priorities can change, technologies can alter the warfighting landscape and there will always be a competition for resources among the services. That said, the Navy’s most recent force structure review revealed a new number: 355.

President Donald Trump’s January 27 executive order calling for a “great rebuilding of the Armed Forces,” a point reiterated in his February 28 speech to Congress.

“I’m signing an executive action to begin a great rebuilding of the armed services of the United States, developing a plan for new planes, new ships new resources and new tools for our men and women in uniform,” Trump said at a Pentagon ceremony.

During the campaign Trump called for a 350-ship Navy, which tracks with the Navy’s own force structure review that concluded that 355 ships were needed to meet combatant commander demands.

Trump has directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to conduct a 30-day “readiness review” to determine “readiness conditions, including training, equipment maintenance, munitions, modernization and infrastructure.”

The Navy conducted its own force structure assessment and commissioned two other studies to examine what kind of force the Navy needs going forward.

Another study by MITRE said the Navy needs 414 ships, including three more nuclear aircraft carriers, nearly double the number of cruisers and destroyers requested in the Navy’s 355-ship plan (from 84 to 160), and an increase of 20 more attack submarines. MITRE’s analysis would cancel the littoral combat ship (LCS), but would create some new classes of ships, such as conventionally powered light carriers and diesel submarines, for example.

The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment (CSBA) concluded that 340 ships are required, plus an emphasis on unmanned vessels—such as smaller combat craft and sub hunting drones--to augment ships and manned aircraft to conduct a variety of operations.

The CSBA study points to small combatants, like the Swedish Visby missile corvette, as a way to achieve numbers while maintaining lethality. Sen. John McCain’s recent white paper also proposes small patrol ships. And while there have been criticisms of the fighting capability of LCS, the Visby is an example of significant combat power on a small platform.

The 640-ton Visby has a BAE Bofors 57 mm gun, the same as LCS and the Coast Guard’s National Security Cutter and Offshore Patrol Cutter, which can use very capable 3P ammunition; RBS15 anti-ship missile; antisubmarine torpedoes and can lay mines. There’s space and weight margin for 32 surface-to-air missiles. It has a hull mounted sonar, variable depth sonar and towed array; Saab 9LV combat management system; Saab Sea Giraffe AMB 3D surveillance radar, and Saab Ceros 200 stealth fire control radar system. And the combat system aboard Visby would easily fit on an LCS-sized ship. It takes many years to bring a new class of warships from the drawing board to the sea buoys. There are existing proven designs at sea today with the attributes the U.S. would need. One example, the Danish Iver Huitfeldt class of frigate visited Baltimore during a recent Flexible Ships Forum co-sponsored by the American Society of Naval Engineers (ASNE) and the Society of marine Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME).

Counting Ships

In all of these ship counts, the total depends of what you count as a ship. This varies, so the numerical comparisons are not always apples to apples.

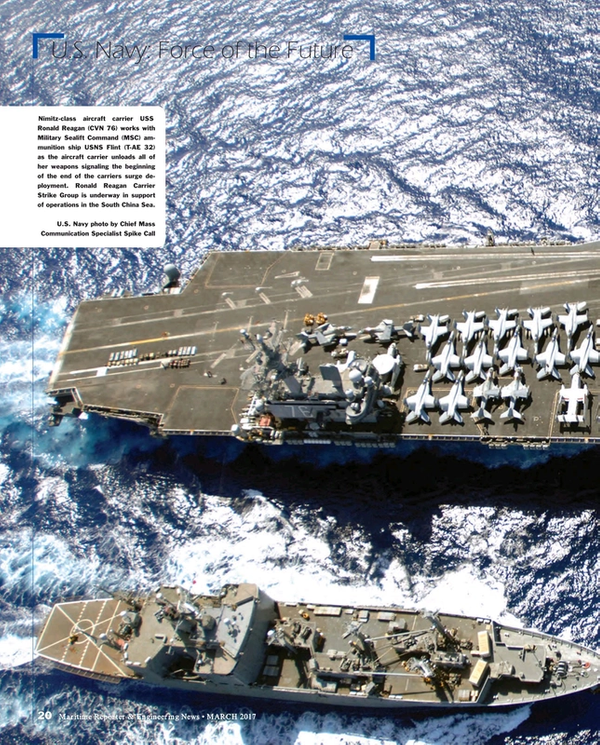

When counting ships, some ships operated for the Navy by the Military Sealift Command are not combatants, but can have a direct role in supporting combat operations, such as replenishment ships, the expeditionary transfer dock (ESD) and expeditionary mobile base (ESB). MSC’s expeditionary fast transports are essentially high-speed commercial roll on-roll off ferries, and can be adapted for a number of theater security cooperation missions.

Ron O’Rourke, an analyst with the Congressional Research Service, said paying for a bigger fleet comes with a big price tag. “CRS estimates that procuring the 57 to 67 ships that might need to be added the 30 - year shipbuilding plan to achieve and maintain a 355 - ship fleet—a total that equates an average of about 1.9 to 2.2 additional ships per year over the 30 - year period—could cost an average of roughly $4.6 billion to $5.1 billion per year in additional shipbuilding funds over the 30 - year period, using today’s shipbuilding costs. These additional shipbuilding funds are only a fraction of the total additional cost that would be needed to achieve and maintain a 355 - ship fleet instead of 308 - ship fleet.”

While O’Rourke said expanding the fleet will create jobs, he also said the Navy officials have also identified readiness as a priority, and that maintaining and sustaining the fleet is also important to maintaining force structure.

Congressional Support

According to Paul Pedisich, author of a new book from the Naval Institute Press: Congress Buys a Navy: Politics, Economics, and the Rise of American Naval Power, 1881-1921, the president and the secretary of the Navy both need Congress to fund the fleet.

“The Secretary of the Navy’s budget must be vetted through the Joint Staff, and the Defense Secretary then reconciles the Army, Navy and Air Force submission to the President’s Budget (PRESBUD). But even the president can’t actually fund the Navy or the other services,” said Pedisich. “That’s the job of Congress, which authorizes and appropriates all federal spending.”

“Obama had no money. Trump has no money,” said Pedisich.

“For years it has been the budget that has driven the strategy. I think we ought to be looking at things the opposite way,” said Rep. Rob Wittman (R-VA), chairman of the Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, speaking at the Surface Navy Association’s Annual Symposium in January in Crystal City, Va. “I think the strategy ought to be driving the budget. We ought to ask the fundamental questions ‘what does it require for us to do the things that this nation needs to do in order to provide presence and power projection and defending this nation?’ And then say, ‘How do we make the budget decisions to make that happen, understanding that there’s always going to be a gap?’ But the only way we understand that gap, and the only way that Congress makes the priority decisions that it must make – that it is constitutionally required to make – is to have a discussion about what that strategy should be. And I think that that is what’s just been laid out before us with the Navy. The Force Structure Assessment for 2016, I think, lays that out perfectly. If you look at the assumptions that that force structure assessment is based upon, it’s based upon the demand signal from the combatant commands. What are the needs? What are the combatant commands see that they need in order to make sure that they are providing for this nation’s presence, for power projection, and make sure we deter and respond to adversaries around the globe. Pretty simple and straightforward.”

Wittman said the Navy’s plan is spot-on.

“This year’s Force Structure Assessment is a very accurate reflection because it takes the demand signal from the COCOMs (the operational combatant commanders), it looks at that in context of what’s happening around the world, and what we can realistically do and achieve – and it says the Navy should be 355 ships. I think that that is exactly where we need to be and it’s very close to what the incoming administration says the Navy needs to be sized at. So that’s our target. That’s where I believe Congress, the House Armed Services Committee, needs to look at and has to figure out ‘how do we achieve that?’ Now our job is to ask the questions about how we did we arrive at that number?”

Simple and straightforward, maybe, but it comes with a price tag.

“The Congress’ job, obviously, is to say, ‘Okay, how do we authorize that and then how do we fund that? How do we make those critical decisions?’ And I am confident that, working hand-in-hand with the Navy, that we could meet that goal and we can get to that 355-ship navy. I think the capacity is there in our industrial base to do that,” Wittman said. “I think that what they have now as far as hot production lines, mature designs, is there, I think the industrial base can provide all of the different support mechanisms, the systems are all in place for us to do that. It’s our job to make sure that we address the situation of the resources. And then, also, it’s not just capacity in the industrial base, but it’s also capabilities. How do we make sure we have the sailors to go along with those great platforms to make sure we sustain it? And then the ultimate question that comes is ‘How long does it take us to get there? How many years will it take to make that happen?’”

Rep. Byron Byrne (R-AL) said the Congress and the Navy will have to think differently to grow the expectation for the fleet from the current force of 274 ships, to the 308 that have been funded for, to 350-plus. “The hardest part of getting to a 350-ship Navy will be funding. We have to break the cycle of passing continuing resolutions in Congress. As many of you know, the continuing resolutions cripple our defense, they cripple our ability to build the ships that we need to build, and to make sure that we have sailors that are prepared and have the readiness they need in order to do the job we expect them to do.”

“In order to do that, and in order to meet the funding we are going to have to have for a stronger, bigger Navy, we are going to have to reverse this whole concept of sequestration,” Byrne said.

Byrne said that some members of Congress say that defense spending should be treated like at every other part of the budget. Byrne disagrees. “It’s fundamentally different, and fundamentally more important, and if we do nothing else, we make sure that we provide that adequate resources that it’s going to take to make sure we defend the American people.”

“There is no greater priority for the federal government and the United States of America than provide for the safety and security of our citizens,” Byrne said. “And that includes a strong, and fully capable Navy.”

“Article I of our Constitution grants the Congress the power to raise an army when needed, but it directs the Congress to provide and maintain a navy,” said Byrne. “Once again, that goes back to the very beginning of our Republic. Our ability to control the seas is challenged by new and evolving threats: China, Russia and Iran. Growing threats and demands are best met with a strong and comprehensive maritime response. The value importance of our naval assets to security and stability here at home and around the world has never been greater.”

More people

At the height of the Regan build up, there were 594 ships in the Navy inventory, but with the end of the Cold War, the U.S. fleet began to decline in size, exchanged for the ephemeral “peace dividend.” This included the number of ships, number of different classes of ships, personnel and the engineering workforce behind them all.

The Navy and industry both need to address the aging workforce with a human recapitalization program at the same time it needs to significantly grow the number of engineers and technical experts to design, build and manage the fleet.

“In the FY 88, 90 and 91 budgets, we had 15, 21 and 31 ships in the appropriations for those three years in a row,” recalled Vice Adm. Thomas Moore, commander of Naval Sea Systems Command. “In the last 10 to 15 years we’ve been happy to get seven or eight ships in the budget.”

“In 1990 we had in 1,092 people in the engineering directorate, NAVSEA 05. In all of NAVSEA, including the PEOs, we had about 4,500 people to manage these ships. And we had about 2,000 people in our Supervisors of Shipbuilding.

“By 2005 we had less than 290 ships. We cut the fleet in half in a 15 year period, which coincided with a rather precipitous drop in our headquarters personnel at NAVSEA and in particular NAVSEA 05, which went down to 251. Today we are at 568 and we continue to ramp back up,” said Moore.

“We continue to focus on growing. We anticipate being about 750 by 2025 based on the current 30 ship shipbuilding plan. If we get bigger, if we want to get to 355 ship, we’re clearly going to need more,” Moore said. The thought of increasing fleet size would be welcomed by the combatant commanders as the demand signal exceeds the availability of ships. And industry would obviously like more work. However, according to Rear. Adm. Michael Jabely, a surge in production isn’t a simple proposition, as his comments at the recent Surface Navy Association Symposium would indicate.

“We have the capacity to increase shipbuilding that would be necessary to get the 66 attack submarines, I would say we have the potential. We’ve obviously done it before: we delivered as many as six Los Angeles Class submarines in one year in the 1980s, at the same time that we were building the Ohio Class SSBN. So the potential is there. The question is at what point do you need to start building more facilities, hiring more people? We’re already in the middle of a facilities expansion and a significant employee ramp-up at our ship builders, just to handle the increased demand signal brought by the Columbia SSBN. We have to figure out how to get the Navy the 66 attack submarines in the right amount of time, with the necessary increase in facilities and employees, without breaking the submarine construction enterprise. So we’re doing that hard work right now to figure out what the recommended posture is to get us to 66.”

(As published in the March 2017 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News)

Read Trump's Navy: A Look at the Future US Navy in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of March 2017 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from March 2017 issue

Content

- Cabotage Rules Changes Proposed page: 14

- Chantier Davie Shipyard: Competitive Value of Integrated Shipbuilding Tech page: 16

- Naval Design: The Human Role page: 18

- Trump's Navy: A Look at the Future US Navy page: 20

- Singapore’s Survivability page: 28

- Transportation Electrification Arrives at the Waterfront page: 34

- New Fuel Regs Drive Scrubber Business page: 38

- Case Study: 18-day Exhaust Gas Scrubber Install page: 42

- Clean Shipping on the Great Lakes page: 44

- Fast Small Ship Simulator page: 52

- Simulation: Delgado Maritime & Industrial Training Center page: 54

- Simulation: The Centre for Marine Simulation page: 56

- Simulation: Maritime Professional Training page: 58

- Simulation: CSMART page: 60

- The (Really) Big Lift page: 70

- Op/Ed: Shiphandlers Beware page: 84

- Interview: Crystal CEO Edie Rodriguez page: 86