Liberty

-

- Ugly Ducklings & Steaming the Way to Victory in WWII Maritime Reporter, Jan 2014 #32

The design and construction of WWII Liberty cargo ships revolutionized shipbuilding by overhauling the blueprint process and standardizing on commonality of parts, welding, pre-fabrication and assembly line construction.

Give me Liberty, or give me death!” a rallying cry of the Revolutionary War, got a second act in World War II. This time the call was more like, “Give me Liberty ships, and make it quick!,” as the country, desperate to build up its outdated flotilla of cargo ships and devastated naval fleet, bet big on a homely vessel that touched off a ship-building revolution and became key to winning the war

“Built by the mile and chopped off by the yard,” Roosevelt promised the no-frills Liberties would form a “bridge of ships” across the Atlantic. And they did. “Without the supply column of Liberty Ships that endlessly plowed the seas between America and England, the war would have been lost,” declared a grateful Winston Churchill:

That’s big praise for what were essentially dumpy, lumbering vessels – dubbed “ugly ducklings” after Roosevelt, in his generation’s version of an ill-advised tweet, described the Liberty as “a dreadful looking object.”

An exaggeration perhaps, but in truth, the Liberty wasn’t much to write home about. They were throwaway ships with a five-year life expectancy, notes Prof. Joshua Smith, interim director of the American Merchant Marine Museum at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point. “The Liberty cost $2 million to build, but could carry $87 million worth of cargo,” says Toni Horodysky, editor of the American Merchant Marine at War website (usmm.org). Hence, “If it made a one-way voyage, it paid for itself.” It’s estimated the Liberties delivered 75% of the cargo used in the war.

The full scantling type Liberty had a range of 17,000 miles, a carrying capacity of about 10,800 tons, steam-operated winches and was propelled by an 1870’s engine design - a triple expansion reciprocating steam engine fueled by two oil-fired boilers, single screw, 2500 HP, running at a top speed of 11 knots. They ran about 440 feet, had a raked stem and cruiser stern, a contra-balanced rudder, a windlass and warping winch, two full decks, seven watertight bulkheads, five cargo holds, and a set of defensive armament.

Less is More

Looks aren’t everything; its genius lay in the design’s embodiment of a clichéd rule of thumb that summed up the marching orders for wartime ship building: keep it simple stupid. For example, although ships of that era had been running on steam turbines, the old-fashioned piston engines were easier to make, operate and repair - important considerations when materials are limited, time is of the essence and the workforce is green.

That simplicity opened the door to enabling radical changes on every level – cost, time, modularity and commonality of systems and parts – in the construction and design of the Liberty and other ships going forward.

Under a government plan that stretched back to 1936, a record-setting 2710 Liberty-class ships were built between 1941 and 1945, at 18 mostly “green field” U.S. ship yards - many of them hastily built from the ground up around ships already under construction. A combination of wholesale adoption of more simple construction methods - chief among them welding - standardized vessel and component plans, and a radical switch to prefabrication and assembly lines, enabled U.S .shipyards by 1943 to crank out the badly needed transports faster than the German U-Boats could sink them.

That speed was critical. Germany’s efforts to secure victory at sea by winning a tonnage war were going swimmingly through 1942, having taken out 3,000 Allied merchant ships, of which only 900 were replaced. This made the American production speed, and ability to maintain a steady stream of supplies to the front, decisive factors in winning the war.

The American “manufacturing miracle” was based on a ship design that made its way to the U.S. as part of a call for help Britain. Unable to replenish its battered fleet, Britain was forced it to turn to the U.S. in 1940 to build 60 10,000-ton deadweight capacity steamers, to be based on a vintage ship design dating back to 1879 from Sunderland, England.

The design for those steamers became the basis for the U.S.-flagged Liberty ships, but the seed for these “workhorses of the war” was actually sown during a failed attempt to bolster the U.S. merchant marine during the first World War. The United State didn’t enter that war until midway through 1917. The Germans surrendered less than two years later before most of the 2,500 ships that were being built were ready to be launched. “It was a day late and a dollar short,” says Capt. Patrick A. Moloney, acting executive director of the National Liberty Ship memorial and master of the SS Jeremiah O’Brien. Embarrassingly, some of that glut was scrapped, some were sold, some mothballed. But with the stock market crash and resulting Depression, only two cargo ships, a few tankers and a small number of passenger ships were built in the U.S. in the years that followed.

“What they learned is that you have to have a plan, and the government has to intervene strongly. You can’t just trust private businesses to do this,” says Smith. “Next [war], we wanted to hit the ground running,” adds Moloney.

Laying the Foundation

By 1936, with the winds of war stirring once more in Europe, over 90% of the U.S. merchant fleet was more than 20 years old, and its complement had dwindled to a combined 1,340 cargo ships and tankers - an estimated 14% of the world’s tonnage. Roosevelt took action. By the time he was through, at the end of the war, the U.S. would hold 60% of the world’s tonnage.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1936 sought to ensure development of an adequate American merchant marine via government subsidy, and also established the U.S. Maritime Commission, which was tasked with building 500 modern cargo ships and tankers in 10 years – a goal it exceeded by more than 10 times over in just four years.

The government, meanwhile, needed a lot of merchant ships, and it needed them yesterday, so in January 1941, Roosevelt further announced a $350 million Emergency Shipbuilding Program to build both merchant and military ships. This was followed in 1942 by the War Shipping Administration, tasked with overseeing the operation of the new fleet of merchant ships, and successive orders for ever more Liberty Ships. Part and parcel of this effort was finding people to build new ship yards all over the country (see chart) as most of the existing shipyard activity was based in urban areas on the east coast with little option to expand, and what space they had was devoted to Naval orders.

The new ship yards were going to need a lot of cheap land and a lot of labor, factors that made the South and West Coast particularly attractive. Leading the way was industrialist, builder and production wizard Henry J. Kaiser, who built seven of the 18 shipyards (see chart on page 35) and set up a consortium called Six Services Inc. with Todd Shipyards. Among the innovations to fall out of Kaiser’s shipyards were assembly line construction and the first Health Maintenance Organization, a precursor to today’s Kaiser Permanente.

The British ship design intrigued the Maritime Commission, which was looking to build its first generation of Emergency Class (EC) cargo ships quickly and cheaply, and wanted all the shipyards involved to build the exact same ship in tandem. “The way to build quickly is to use what is already proven,” points out Richard Neilson, dean and professor of naval architecture at the Webb Institute.

The Commission turned to Gibbs & Cox, Inc., an independent naval architecture and engineering firm that ended up designing more than 70% all WWII ship designs, and which had already been retained by the British to supervise its cargo ship order. The commission asked Gibbs & Cox both to adapt the British design to American needs and shipbuilding practices, and to help standardize the design and process across all the shipyards. “They wanted fast production of a repeatable design at a low cost per ship; we said it can’t be done the traditional way,” said Shawn Tallant, Gibbs & Cox Vice President, Business & Strategy Development.

A Revolution in Design

Getting all the shipyards on the same page would create efficiencies, speed and economies across the board. It would make it possible to get identical parts and components from a broader array of manufacturers, who in turn could make fewer products to supply more customers – no customization necessary. It would be nothing short of revolutionary.

Up until about 1940, explains Tallant, most ships were custom-built, one at a time, in a single yard, using a set of plans that left many profitable details up to the imagination of the individual boat yard. To mass produce a large number of ships, there needed to be a huge paradigm shift. Gibbs & Cox made every component on the ship well-defined and interchangeable, according to Mike Schneider, a retired Navy captain, Project Liberty Ship member and SS John W. Brown volunteer.

But the starting point for that transformation was the blueprints themselves, “which meant you had to change the entire design process,” said Tallant. Every design firm had their own blueprint symbols, for example, which led Gibbs & Cox to create a common set of symbols covering not just all the parts of a ship, but extending to purchase orders, graphs, charts, reports and statistics. “At the peak of the war, we were pushing out 10,000 blueprints a month and almost 6,700 purchase orders a day. It was a huge amount of paperwork.”

Standardization enabled centralization of the procurement process, and streamlining the paperwork made it easier to keep track of, order, and allocate constantly in short supply materials and parts, which could be routed away from a ship still under construction to one almost ready for launch when the need arose. These changes – probably one of the earliest examples of just-in-time manufacturing - along with the introduction of modular construction, are the foundation of cost-effective shipbuilding today, notes Tallant. “And this was all done by phone call or letter, before the advent of computers or the internet,’’ marvels Schneider.

The latter is where “Hurry up Henry” Kaiser came in. He set up his shipyards as assembly plants where thousands of components preassembled at other factories were finally laid in place. He set up training schools onsite to teach unskilled laborers and switched from riveting to welding, creating Wendy the Welder. Changes like this were said to have reduced man-hours by a third, cut ships costs from $2 million to under $1.7 million, and advanced ship construction into the next century. On average, it took 592,000 man-hours and 6,850 tons of steel to build a Liberty Ship.

Modern Shipbuilding

The most revolutionary change of all was the decision to go full bore to prefabrication and assembly lines. The Liberty was comprised of some 250,000 parts, a portion of which would come preassembled – i.e. the bow and parts of the deck house, bridge, double-bottom sections, stern-frame assemblies and bow units. Some estimates claim there was 43 miles of welding, 5 miles of wiring ad 7 miles of piping in each ship.

Taking this modern factory approach demonstrably shrunk construction time from the 10-12 months required in 1917 to 244 days at the start of WWII to an unheard of average of 30-42 days by the peak. Some Kaiser shipyards could do it in 2 weeks. By war’s end, as many as three Liberties a day were being launched. Drilling down into the actual physical construction, a decision was made to go to welded hulls, which required less skill, and a third less labor. “You can lay a line of soder much faster than someone can heat the rivet through,” says Horodysky. It also saved on metal as plates were now butted instead of overlapped, and that saved on weight, adds Schneider. The aggressive oversight of the commercial merchant fleet, combined with standardization and revolutionary techniques, paid off. By the end of the war, the Maritime Commission had succeeded in running the most productive shipbuilding effort in history. From 1941 to 1945, the U.S. increased its shipbuilding capacity by more than 1,200%, producing 5,777 merchant and naval ships - a feat unmatched since.

A few lessons were learned along the way – some the hard way.

First, the Liberty design was tweaked to improve on the British predecessor. Changes included:

• Moving to a single, mid-ship house to accommodate the crew, which reduced piping and heating needs.

• Replacing three Scotch coal boilers with two water tube boilers.

• Reshaping the hull into more of a straight line to better support mass production to cut down on the need for furnaceing to shape plates.

• Increasing the size of the bilge radius to help from a hydrodynamic and structural standpoint.

• Increasing the size of the parallel mid-body to make the ship faster, easier to construct and provide more cargo volume

• Using a contra rudder to improve speed and maneuverability

• Inventing a cold-rolling process to save on steel.

“Kaiser Coffins”

One thing they couldn’t improve much on was the ship’s raid roll motion, which crew discomfort aside, created instability and stress on the hull. “They were terrible to sail in; it wallowed in heavy seas,” says USMM.org’s Horodysky. Instead of sending empty ships off to rock and roll the entire way home, one solution was to load solid ballast into the holds for stability.

Welding came with its own set of problems, chief among them cracking. Square angles built into the hatches were aiding cracks caused by fatigue, a problem rectified by rounded corners on those hatches. More serious was cracking that could occur where there were no rivets to stop them; cracks zip past a weld. After some ships broke open at sea, earning Liberties the name “Kaiser coffins” in some circles – a crack arrestor strake plate was put on ships, forward mast to after mast. Some yards also mixed riveting and welding to avoid that issue.

Brittle steel was aserious problem. When an overloaded (stressed) ship was exposed to freezing water, the less than optimal steel could crystalize, lose its ability to flex, and develop fractures, often near the midship accommodations. “Once a crack develops in brittle steel, the speed of the crack is like 6 feet per second, virtually instantaneous. The way they stopped it was to drill a hole on each end of the crack,” says Moloney. Abutting arrestor plates helped too since was there was no chemical connection to propagate the crack from one plate to the other, explains Prof. Neilson.

Post War Fleet Disposal

With the armistice, the U.S. found itself with over 40 million tons of shipping - an enormous glut, much of which it never expected to survive the war. A little more 4 million tons was in merchant marine vessels. In short, it had more ships than cargo to move, says Schneider. Congress almost immediately passed the 1946 Merchant Ship Sales Act, to enable sale of surplus ships to domestic and foreign buyers.

America’s overage allowed allied nations to rebuild devastated naval fleets, and also provided the foundation for what became the Greek shipping magnates. Commercial buyers like Aristotle Onassis were able to buy Liberties cheaply and then “man them with bargain basement crews working for a song out of devastated Europe,” observes Moloney. “It promptly drove the U.S. Merchant Marine off the water because they worked for so much less,” he adds. These sales also helped former enemy nations rebuild their merchant marine capacity.

The Liberties were also used to transport relief supplies to a stricken Europe and Japan in the aftermath of the war. Some were pressed into service for the National Defense Reserve Fleet, which moors ships along the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts. A percentage was mothballed, rehabbed and saw service in Korea and Vietnam. More than 40 were deliberately sunk to create breeding reefs off Florida. King’s Point took over some for training purposes. Most ended ignominiously, sold for scrap.

Just two remain fully operational: the SS Jeremiah O’Brien is docked in San Francisco, and is run by The National Liberty Ship Memorial; and the SS John W. Brown is berthed in Baltimore, and is maintained by Project Liberty Ship. Both ships are taken out on the water several times a year on cruises open to the public.

The 18 wartime shipyards immediately shut down; all were sold off to other entities, some many times over. The various government agencies created during the war to oversee ship construction were also disbanded. The U.S. Maritime Commission was closed in 1950 and essentially re-emerged as the United States Maritime Administration, which is under the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The ships may be mostly gone, but their legacy lives on. They helped to save Europe twice - first during the war and then through humanitarian deliveries and as fodder for rebuilt fleets in other countries. Many of the shipbuilding techniques and design conventions have become standard. The shipyards contributed greatly to one of the countries’ largest demographic shifts, as workers climbed out of the Depression on the backs of wartime jobs. The newly diversified workforce broke barriers for women and minorities, opening the door for the first time to the American labor market. Entire neighborhoods and new schools were built to accommodate shipyard families, and early efforts to provide affordable health care to working families have morphed into today’s HMOs. History will record that these lowly emergency class vessels lived up to the Liberty name, and then some, well beyond their supporters’ wildest dreams, freeing so many, here and abroad, from the oppression of outdated thinking and terrible tyrants.

Liberty Ships at a Glance

• Class of Ship: EC2-S-C1: ‘EC’ for Emergency Cargo, ‘2’ for a ship between 400 and 450 feet long (Load Waterline Length), ‘S’ for steam engines, and ‘C1’ for design C1.

• Nicknames: Ugly Duckling, Workhorse of the Deep

• Design: Based on British-flagged Dorrington Court, designed and built by J.L.Thompson & Sons of Sunderland in 1939, and brought to the U.S. by the British Merchant Shipbuilding Mission in 1940, seeking to get 60 ships built in the U.S. The U.S. Maritime Commission adopted the design but asked naval architects Gibbs & Cox to make alterations for speed and American shipbuilding practices and sent the standardized plan out to all the shipyards.

• First ship launched: S. S. Patrick Henry (Sept. 27, 1941); the Benjamin Warner was the last Liberty launched on the West Coast, on July 1, 1944, while the SS Albert M. Boe was the last overall, launched on Sept. 25, 1945.

• Number built: 2751 was the goal; 2710 were built between 1941 and 1945.

• Average cost to build: Under $2M/hull at the start of the war. By war’s end, Kaiser was producing ships for about $1.75M/hull. Some estimates go as low as $1.5 million plus.

• Materials: 3,425 tons of hull steel, 2,725 tons of plate, and 700 tons of shapes, which included 50,000 castings. The 250,000 parts were pre-fabricated in 250-ton sections and welded together in about 70 days.

• Power Plant: an oil-fired, triple expansion 2,500 hp, 24-ft. high, 140-ton, 3-cylinder reciprocating steam engine capable of speeds of 11 knots. The Hendy Ironworks in Sunnyvale, Calif., produced a record breaking number of 754 Liberty Ship engines at the rate of one every 40.8 hours.

• Average time to build: the Patrick Henry, the first ship, took almost 8 months to build. The average dropped to 42 days per ship by mid war and some yards pulled it off in 16 days. As a publicity stunt, the SS Robert E. Peary, was built in world record time of 4 days, 15 hours, 26 minutes at the Kaiser shipyard in Richmond, California (plus another three days to be fitted out.) By 1943, three Liberty Ships were being completed each day

• Merchant Marine: The civilian mariner workforce rose from about 55,000 on December 7, 1941 to 215,000 in March 1945, and rose to over 250,000 by the war’s end.. A pre-war merchant fleet of 1,340 cargo ships and tankers expanded to at least 4,221 U.S. merchant ships by war’s end. The U.S. Merchant fleet went from 14% of the world’s tonnage at the start of the war, growing to 60% after the war.

• Number lost: 243. Overall Merchant Marine casualty rate was the highest, estimated at 1 in 26, during the war. The Merchant Marine served in World War II as a Military Auxiliary. Of the nearly quarter million volunteer merchant mariners who served during World War II, over 9,000 died.

• Crew: A typical roster included 38-45 or so merchant mariners and anywhere form 13-just under 30 Naval personnel. Each ship had an attachment from the U.S. Navy Armed Guard, tasked with defending U.S. and Allied merchant ships from attack. They served as gunners, signal men and radio operators.

• Postwar Dispersal: Under the Merchant Ship Sales Act of 1946, most sold off cheaply to foreign shipping companies, including Onassis and the Japanese. Some were deployed in Vietnam, others were scrapped, and others were nmothballed.

• Number remaining today: Two fully operational Liberty ships remain afloat today: The SS Jeremiah O’Brien is docked in San Francisco, and SS John W. Brown is berthed in Baltimore.

Sources: American Merchant Marine at War (www.usmm.org); Project Liberty Ship (http://www.liberty-ship.com), The National Liberty Ship Memorial (http://www.ssjeremiahobrien.org/) , www.merchantnavyofficers.com, http://www.sunderlandmaritimeheritage.org.uk, National Liberty Ship Foundation, WW2Ships.com, National Park Service and Liberty Ships and Associated Designs By Sam Peters, “The Liberty Ships” by L.A. Sawyer and W.H. Mitchell, The National American Archives.

The Author

Patricia Keefe is a veteran business journalist and editor who has covered high-tech industries and maritime topics. She discovered while researching this story that her father came within a hair’s breadth of being assigned to a Liberty ship. After finishing Navy boot camp, the 16-year-old was sent to armed guard camp in Little Creek, Va., coincidently at the same time the father of a future son-in-law was also sent there. (That man went on to lead naval gunnery crews on several Liberty ships, including part of the first convey to make it across the Mediterranean without being attacked). Her father was sent onto the armed guard camp in Brooklyn, N.Y., which was looking to staff Liberties. However, a naval detachment came through seeking personnel to crew the shiny new U.S.S Hancock aircraft carrier, and scooped him up, thereby making him one of that ship’s original plank owners.

Necessity …

The Mother of Invention

Plato said it and Robert W. Fernstrum proved it, leading to the creation of R.W. Fernstrum & Company, a ubiquitous name in commercial maritime circles.

Necessity is indeed the mother of invention, a point proven time and again throughout history. For better or worse, war historically has proven the impetus for invention, as was the case with Robert W. Fernstrum.

R.W. Fernstrum & Company of Menominee, Mich., is a leader in engineering and manufacturing keel cooling technologies, and today remains a privately held, third-generation company run by brothers Sean and Todd Fernstrum, grandsons of founder Robert W. Fernstrum.

The company came to fruition in 1945 when Robert W. Fernstrum patented the first rectangular tube keel cooler with an angled header for the United States Army and Navy.

As Sean Fernstrum, President, explained, during World War II the U.S. Navy encountered engine cooling problems with its landing craft (pictured above) – a problem discovered during a mock invasion off of Iceland—and required a new closed circuit cooling system.

“As WWII started, Gray Marine was building landing craft for the Army. When the Army conducted a mock assault of Iceland, less than half of the landing craft made it to shore,” said Sean Fernstrum. “The ice plugged up all of the strainers and it became a nightmare. So the Army went back to Grey Marine and said ‘you’ve got a problem.’ And (the management of Gray Marine) went to its Chief Engineer, my grandfather, and said ‘you’ve got a problem!’ Out of that problem he ended up designing the prototype of our keel coolers.”

So the first real use of the R.W. Fernstrum coolers was on a landing craft, which didn’t actually occur until the conclusion of WWII, but are found on military landing craft from the Korean conflict onward. The company officially got its start in 1949, and expanded its references to include the Army Corps of Engineers then shrimp boats, and today includes a wide variety of commercial craft globally. In 2014 R.W. Fernstrum celebrates its 65 anniversary.

G. Trauthwein

(As published in the January 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - www.marinelink.com)

-

- WW II Liberty Ship Leak-free after 70 Years Maritime Reporter, Jun 2014 #68

Seventy years later and still leak-free: World War II Liberty Ship tests longevity of grooved piping systems To address the sudden need for supplies overseas during World War II, the United States government launched the Emergency Shipbuilding Program in 1941 that resulted in the construction of more

-

- Announce Speakers For Liberty Corrosion Course Maritime Reporter, Sep 1981 #83

Participants in the marine seminars being given as part of the 19th annual Liberty Bell Corrosion Course were announced recently by conference organizers. The course will be held September 28-30 at the Marriott Hotel, Philadelphia, Pa. In the marine seminars, featured participants in a segment

-

- New Vessel Joins Circle Line Fleet Maritime Reporter, Jul 1977 #18

Miss Freedom, a new 500-passenger Circle Line vessel that will inaugurate ferry service to Ellis Island from both Battery Park and Liberty State Park (Jersey City, N.J.) was christened recently at dockside ceremonies at the Circle Line Pier 83 in New York City. New York Mayor Abraham D. Beame and

-

- Ferry Operations: A Tragedy Averted Marine News, Nov 2017 #86

embodiment of that maritime metric. For any first time visitor to the Big Apple, the trip probably wouldn’t be complete without seeing the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. To that end, Statue Cruises’ main focus is to create a smooth passenger experience and serve as the gateway to the Statue of Liberty

-

- Blount-Barker Shipbuilding Formed Maritime Reporter, Jan 2001 #26

vessel. Barry's business, Circle Line, was subsequently awarded the National Park Service's contract to handle tourist excursions to the Statute of Liberty. The Miss Liberty remains in operation today, and has carried more than 60 million passengers from Manhattan to the Statute of Liberty. This vessel

-

- Baldt Marks 85th Year As Major Supplier To Marine/Offshore Industries Maritime Reporter, Aug 1986 #37

mooring release systems. The company evolved over the years from a manufacturer of chain and anchors, whose credits include supplying the first WWII Liberty ship with DiLok chain, to a broad-based marine supply company. Current products include an award-winning mooring release system designed for offshore

-

- On Patrol: North River Boats Maritime Reporter, Mar 2014 #48

ALMAR by North River Boats of Roseburg Oregon recently built and launched the first of three 29 x 10 ft. Liberty Walk Around vessels destined for the San Francisco area. The Liberty family of boats features a Wing Hybrid Foam/Air Fender protecting the exterior perimeter of the boat. Capable of speeds

-

- Grooving the Way: Back to the Future Marine News, Jul 2017 #47

. The advent of World War II forced U.S. builders to more quickly produce merchant hulls in quantity, and with good quality. Eventually, more than 2,170 Liberty Ships and later, 531 Victory Ships were produced – at the sometimes astounding speed of one every 30 days. That process was surely sped along was

-

- MN 100: Blount Boats, Inc. Marine News, Aug 2015 #16

The Company: Over time, the Blount shipyard has built 363 vessels, including such iconic designs as the 130-foot, 600-passenger Miss Liberty. Built in 1952, the vessel is believed to have carried more total passengers than any other vessel in the world. Hull number 93, built in 1955, the “Blount 65’ made

-

- Non-EU Europe Fishing Fleets: Europe’s Profitable 'Outsiders' Maritime Reporter, Jan 2016 #26

. The traditional Norwegian and Icelandic sjark (say shark) has been made by Seigla into a high-speed (if desired) custom-build. Two Seigur T1100-Liberty auto-liners will be delivered to Norwegian fleet owners in Bodo in 2016. Three sjarker are on order for coastal fishermen. “2015 was a fantastic year

-

- U.S. Merchant Fleet Development Urged By Shipping Executive At New Orleans Conference Maritime Reporter, Jan 1991 #60

Philip Shapiro, president and CEO of Liberty Maritime Corp. and Liberty Shipping Group, New York, offered a number of prescriptions to modernize and strengthen the U.S.- flag liquid and dry bulk fleet when speaking recently at a maritime conference in New Orleans, La. "U.S.-flag shipping can once aga

-

)

February 2024 - Marine News page: 29

)

February 2024 - Marine News page: 29as a problem for the wind operation as a whole,” he said. In the U.S., electricity is very localized, said Tim Axels- son, director of offshore wind at Liberty Green Logistics. “Every state controls its own destiny when it comes to elec- trical markets: how much it costs, who’s going to make it, how you’re

-

)

December 2023 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 35

)

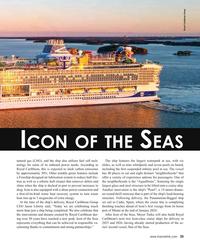

December 2023 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 35? agged ship At the time of the ship’s delivery, Royal Caribbean Group set sail to Cadiz, Spain, where the cruise line is completing CEO Jason Liberty said, “Today we are celebrating much ? nishing touches ahead of Icon’s ? rst voyage from its home more than just a ship being completed. We also

-

)

July 2023 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 36

)

July 2023 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 36from Europe on ship could see them from the water during and entrepreneurs, such as Nathan Handwerker, started selling the years before the Statue of Liberty was built. hot dogs for a nickel, which would eventually turn into the Coney Island was also a place that showcased innovations. For Nathan’s Famous

-

)

February 2023 - Marine News page: 33

)

February 2023 - Marine News page: 33, in Maryland) is set to begin cruises on the Lower Mississippi in Spring, 2023. In late 2022, the com- pany began construction on Ameri- can Liberty, the third new Coastal Cat in the company’s “Project Blue” series, at the same yard. With delivery www.marinelink.com MN 33

-

)

June 2022 - Marine News page: 24

)

June 2022 - Marine News page: 24of the Navy event at Odesa last 4 July. Citing casualty in the Russian war against Ukraine around March the Mk VI new builds in a December 2020 Radio Liberty 3, 2022. Beyond a report on March 6, by Mayor Volody- interview, Ukrainian Navy RADM Alexei Neizhpapa said, myr Novatsky, port city of Yuzhny, of

-

)

February 2022 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 57

)

February 2022 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 57Photo Left: Undated image of STURGIS operating in the Panama Canal Zone. The Decarb Core STURGIS, a former World War II Liberty Ship, was converted into the ? rst ? oating nuclear power plant in the 1960s. Before being shutdown in 1976, the STURGIS’ nuclear reactor, MH-1A, was used to generate electricity

-

)

September 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 73

)

September 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 73in the mix in future, says Wilson. For communications, which has also been involved in designing Equinor’s subsea the XLUUV would, a little like the Liberty system, have a sur- docking station. The locking system, which latches on to the face buoy, that provides the surface communications gateway underwater

-

)

September 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 70

)

September 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 70with light intervention capabilities – that could serve as a resident system, but is initially targeting pipeline survey. How- ever, it also has the Liberty E-ROV, a standalone system comprising an elec- tric ROV with deployment cage, batter- ies and surface communications buoy, so it can be dropped

-

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 30

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 30challenge, he says, “because of the power re- quirements and that also has an impact on how far you can ROV is left on the seabed, for example, like the Liberty eROV system. Could that even mean being able to release the tether? go with autonomy and potentially even tetherless operations, For TechnipFMC

-

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 29

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 29centres in Morgan City, Stavanger Fugro has a ? eet of ROVs, from smaller systems to its own range and soon another in Aberdeen. While Oceaneering’s Liberty of FCV WCROVs, and a network of eight remote operations cen- system (the E-ROV with a cage and battery pack) is 100% re- tres, although WCROVs are

-

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 14

)

July 2021 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 14operations. continues to be a key com- in the offshore renewables segment, the Looking speci? cally at ROV services, ponent for helping subsea Liberty which is a battery-powered elec- a recent industry survey conducted by operators achieve greater tric ROV to support IMR, commission- Kimberlite

-

)

July 2021 - Marine News page: 15

)

July 2021 - Marine News page: 15west coasts, the current increasing momentum in offshore wind power, and of course a growing number of military and governmental projects. We aren’t at liberty to say much about our involvement in military projects, but a great example of our products would be the U.S. Navy MKIV Patrol Boat. This vessel

-

)

January 2021 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 54

)

January 2021 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 54research and survey equipment. Brix Delivers Water Taxi for NJ Golf Course Port Angeles, WA-based Brix Marine delivered a new 4615- CTC luxury water taxi, Liberty National I, to Liberty National Golf Club after launch and sea trials in Port Angeles Harbor. Liberty National Golf Club will use the planing catamaran

-

)

October 2020 - Marine News page: 50

)

October 2020 - Marine News page: 50310-foot lique? ed natural gas (LNG)-fueled plat- LNG and battery systems, a hybrid anchor handling tug form supply vessels (PSV) Harvey America, Harvey Liberty, for ship tendering service, America’s only LNG marine fu- Harvey Power and Harvey Freedom into tri-fuel vessels. eling dock, and will soon take

-

)

August 2020 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 20

)

August 2020 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 20? cant Intellec- enced success. tual Property (IP). It could be in any of the interesting and “hot” disciplines such as AI and Learning, Aug- • Orca / Liberty – Pilot bene? tting both organizations mented Reality, underwater communication, energy and around intelligent bridge assistance and ? eet manage- char

-

)

July 2020 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 9

)

July 2020 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 9industry. Over the last three years, it has been develop- ing the next generation of subsea vehicles, such as the Freedom Autonomous Vehicle and the Liberty E-ROV Resident Vehicle. In late 2019, it launched the Isurus Work Class ROV to allow capable of being remotely piloted from a dedicated onshore

-

)

August 2020 - Marine News page: 16

)

August 2020 - Marine News page: 16at the shipyard was a 130-ft., 600-passenger ferry boat built in 1952 that has carried more than 60 million passengers from Manhattan to the Statue of Liberty for the Circle Line. More recently, the construction and delivery of Atlantic Pioneer, the ? rst U.S. ? agged crew transfer vessel for the Block

-

)

April 2020 - Marine News page: 39

)

April 2020 - Marine News page: 39catamaran for Alaska Tales in Juneau, Alas- with meeting the vessel demand since a lot of older towboats ka; a 46-foot luxury catamaran water taxi Liberty National are still operating out three and it is only a matter of time I for Liberty National Golf Club in Jersey City, N.J.; a 45- before they

-

)

November 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 68

)

November 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 68industry voice with an of? ce While she no longer is a practicing in lower Manhattan overlooking the lawyer as she works in-house, she cred- Statue of Liberty and a global presence, its her legal background with providing a her advice and formula for success to solid foundation for future growth. all

-

)

May/Jun 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 25

)

May/Jun 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 25HSP contractors have already been vetted and approved expedited and micromanaged,” Nevarez said. and can bid to support individual port calls, providing liberty He said the FLCY teams help coordinate parts movements. “If launchers, fuel, trash removal, pumping out chemical holding something is coming into

-

)

April 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 21

)

April 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 21February 14, four ma- jor developers submitted proposals: 1. Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind 2. Empire Wind Project – Equinor US Holdings, Inc. 3. Liberty Wind - Vineyard Wind 4. Sunrise Wind – Bay State Wind LLC, a joint venture of Ørsted A/S & Eversource Energy. • By March 31 New York’s

-

)

Jan/Feb 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 64

)

Jan/Feb 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 64Bridge .................................................................13 Chesapeake Shipbuilding ................................................28 Liberty, Jason ................................................................45 U.S. Coast Guard ...................................46, 47, 49, 50, 56 CLIA

-

)

Jan/Feb 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 45

)

Jan/Feb 2019 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 45plus one better than expected — in the second quarter. Chief Finan- option, means that Silversea’s itineraries encompass all seven cial Offcer Jason Liberty said the market was booked “nicely continents and feature worldwide luxury cruises to the Medi- ahead” in volume and rate for the rest of 2018 and

-

)

January 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 53

)

January 2019 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 53sole in the ? owing, contemporary exterior con- ment. With an intended build time of 3.5 Some 11 years after developing her the main saloon resembles Liberty-style tours with a long bow and extended su- years, she was conceived in 2007 on the original lines, Saunders is pleased to see ? ooring in a Paris