Page 44: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (April 15, 1969)

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 15, 1969 Maritime Reporter Magazine

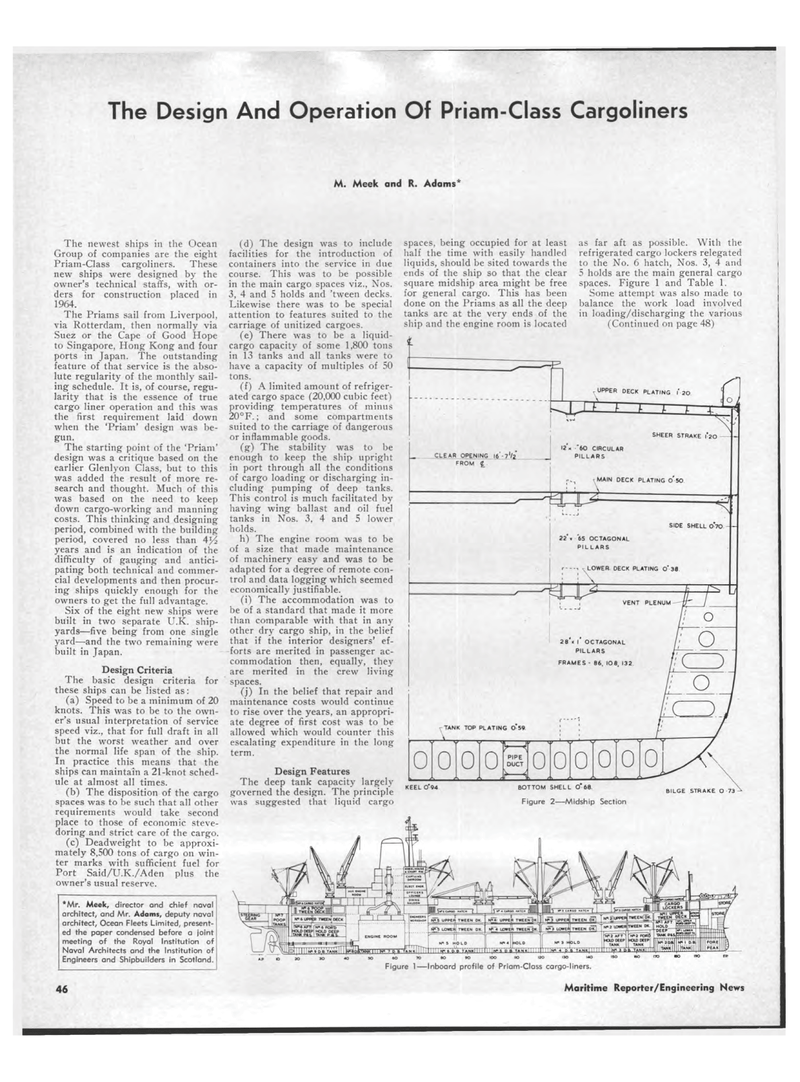

The Design And Operation Of Priam-Class Cargoliners M. Meek and R. Adams* The newest ships in the Ocean Group of companies are the eight Priam-Class cargoliners. These new ships were designed by the owner's technical staffs, with or-ders for construction placed in 1964. The Priams sail from Liverpool, via Rotterdam, then normally via Suez or the Cape of Good Hope to Singapore, Hong Kong and four ports in Japan. The outstanding feature of that service is the abso-lute regularity of the monthly sail-ing schedule. It is, of course, regu-larity that is the essence of true cargo liner operation and this was the first requirement laid down when the 'Priam' design was be-gun. The starting point of the 'Priam' design was a critique based on the earlier Glenlyon Class, but to this was added the result of more re-search and thought. Much of this was based on the need to keep down cargo-working and manning costs. This thinking and designing period, combined with the building period, covered no less than \y2 years and is an indication of the difficulty of gauging and antici-pating both technical and commer-cial developments and then procur-ing ships quickly enough for the owners to get the full advantage. Six of the eight new ships were built in two separate U.K. ship-yards?five being from one single yard?and the two remaining were built in Japan. Design Criteria The basic design criteria for these ships can be listed as: (a) Speed to be a minimum of 20 knots. This was to be to the own-er's usual interpretation of service speed viz., that for full draft in all but the worst weather and over the normal life span of the ship. In practice this means that the ships can maintain a 21-knot sched-ule at almost all times. (b) The disposition of the cargo spaces was to be such that all other requirements would take second place to those of economic steve-doring and strict care of the cargo. (c) Deadweight to be approxi-mately 8,500 tons of cargo on win-ter marks with sufficient fuel for Port Said/U.K./Aden plus the owner's usual reserve. (d) The design was to include facilities for the introduction of containers into the service in due course. This was to be possible in the main cargo spaces viz., Nos. 3, 4 and 5 holds and 'tween decks. Likewise there was to be special attention to features suited to the carriage of unitized cargoes. (e) There was to be a liquid-cargo capacity of some 1,800 tons in 13 tanks and all tanks were to have a capacity of multiples of 50 tons. (f) A limited amount of refriger-ated cargo space (20,000 cubic feet) providing temperatures of minus 20°F.; and some compartments suited to the carriage of dangerous or inflammable goods. (g) The stability was to be enough to keep the ship upright in port through all the conditions of cargo loading or discharging in-cluding pumping of deep tanks. This control is much facilitated by having wing ballast and oil fuel tanks in Nos. 3, 4 and 5 lower holds. h) The engine room was to be of a size that made maintenance of machinery easy and was to be adapted for a degree of remote con-trol and data logging which seemed economically justifiable. (i) The accommodation was to be of a standard that made it more than comparable with that in any other dry cargo ship, in the belief that if the interior designers' ef-forts are merited in passenger ac-commodation then, equally, they are merited in the crew living spaces. (j) In the belief that repair and maintenance costs would continue to rise over the years, an appropri-ate degree of first cost was to be allowed which would counter this escalating expenditure in the long term. Design Features The deep tank capacity largely governed the design. The principle was suggested that liquid cargo spaces, being occupied for at least half the time with easily handled liquids, should be sited towards the ends of the ship so that the clear square midship area might be free for general cargo. This has been done on the Priams as all the deep tanks are at the very ends of the ship and the engine room is located t as far aft as possible. With the refrigerated cargo lockers relegated to the No. 6 hatch, Nos. 3, 4 and 5 holds are the main general cargo spaces. Figure 1 and Table 1. Some attempt was also made to balance the work load involved in loading/discharging the various (Continued on page 48) *Mr. Meek, director and chief naval architect, and Mr. Adams, deputy naval architect. Ocean Fleets Limited, present-ed the paper condensed before a joint meeting of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects and the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland. , UPPER DECK PLATING l"20 \ L | I l l i i i r CLEAR OPENING l6 -?'/2 . FROM £ SHEER STRAKE 1*20 12 « "60 CIRCULAR PILLARS r MAIN DECK PLATING O SO -± "N SIDE SHELL 0*70 22 « 65 OCTAGONAL PILLARS LOWER DECK PLATING 0"38 isr VENT PLENUM o 28 « I OCTAGONAL PILLARS FRAMES - 86, 108. 132 fC3 O YTANK TOP PLATING 0*S« \ \ : 0 0 0 0 ^?4 PIPE DUCT hH 0( D 0 0 0 0 KEEL 0'94 BOTTOM SHELL O 68 Figure 2?Midship Section BILGE STRAKE O 73 Figure 1?Inboard profile of Priam-Class cargo-liners. 46 Maritime Reporter/Engineering News

43

43

45

45