Page 18: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (January 2006)

Passenger Vessel Annual

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of January 2006 Maritime Reporter Magazine

By Joe DiRenzo III and Chris Doane

Two ships collide at sea or in a ship- ping channel. A ship runs aground and oil is spilled. A ship founders and sinks.

All of these are common maritime mishaps that must be investigated to determine why the accident occurred.

Determining why is important to identi- fying potential modifications to safety requirements or practices that may pre- vent future mishaps. However, recon- structing events to determine the "why" is often a most difficult task for mar- itime accidents. Often investigators are faced with two conflicting stories and two sets of emotions, or worse no wit- nesses whatsoever. To resolve the uncertainty, they must search for more concrete evidence.

For centuries the Ship's Deck Log was the traditional method used to record vessel movements and was the primary document for reconstruction. As ship- ping modernized, more internal sources of ship movement information for investigators have been added to the mix. These include: the Engine Order

Log, paper navigational charts, electron- ic navigational positioning systems such as LORAN and GPS, computer systems used to monitor engine performance, and the newest entry - electronic chart.

All of these additional sources of infor- mation on a ship's position and move- ments, when they could be recovered, significantly aided in the efforts to re- construct what a vessel did and when it did it, but gaps remained.

There are also external sources of information on vessel movements, ves- sel interactions and even communica- tions between vessels. Examples include; information recorded by the

Coast Guard's Vessel Traffic System (VTS) in locations such as New York;

Houston; Valdez, Alaska; or by Rescue

Coordination Centers throughout the world. Additionally, the relatively new 2002 Maritime Transportation Security

Act (MTSA)'s requirement for an

Automated Identification System or AIS provides information on a ship's posi- tion and intended movement. Where available, these external sources of ves- sel movement information can provide supporting data to aid a casualty investi- gation, but still more "primary" infor- mation, provided by the vessel itself, is needed.

For years, the maritime industry, insurers, government officials, and other stakeholders have discussed the need for a reliable and durable method for more precisely determining vessel actions prior to a mishap in order to accurately judge causes, fault and liability.

Amongst other data, investigators need to know exactly what heading a vessel was on, what speed, what equipment was running and any changes before an accident occurred. Having watched the aviation industry and their "black boxes" help the U.S. National

Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and investigative agencies of other nations understand the conditions that led to airliner incidents, developing a similar system for ships seemed an obvious solution.

The U.S. NTSB, who along with the

U.S. Coast Guard investigates maritime accidents, pushed for the use of event recorders on ships since the 1970s. "Drawing on its extensive experience with aviation and surface vehicle data recorders, the Safety Board has worked with the U.S. Coast Guard, other agen- cies, and marine industry companies in rulemaking efforts and development of technical standards for [Voyage Data

Recorders]. The NTSB supports the use of these systems not only as accident investigation tools, but also as manage- ment tools." NTSB's position is the result of numerous marine accident investigations in which it "identified the need for VDRs and issued safety recom- mendations related to developing or requiring the systems." (Footnote 1)

In considering a maritime black box, several variables come into play. The system needs to survive an accident and be readily retrievable. Location on the vessel is another consideration, should the system be on the bridge or the engine room adjacent to the systems to be recorded, or located with the emer- gency beacon or life rafts to enhance recovery. Another over-riding issue is industry's ability and desire to produce such a piece of equipment. Any such system needs to be adaptable to many types of ships plying the seas, highly reliable, of reasonable size, economical for ship owners yet profitable for manu- facturers.

Enter the maritime version of a "black box". In accordance with the

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), a Voyage Data

Recorder (VDR) is required on passen- ger ships and new construction cargo ships of 3,000 gross tons and up since

July 1, 2002. Analogous to "black boxes" carried on commercial airliners, the VDR is intended to provide marine accident investigators with data critical to determining why maritime accidents occur. Existing cargo ships have been exempt from the regulation over con- cerns of VDRs interfacing with existing equipment.

VDRs proved their worth to investiga- tors, ship owners and insurers. Post accident data from VDRs has been help- ful in determining the true events lead- 18 Maritime Reporter & Engineering News

SVDR Report

S-VDR - Black Boxes For Ships

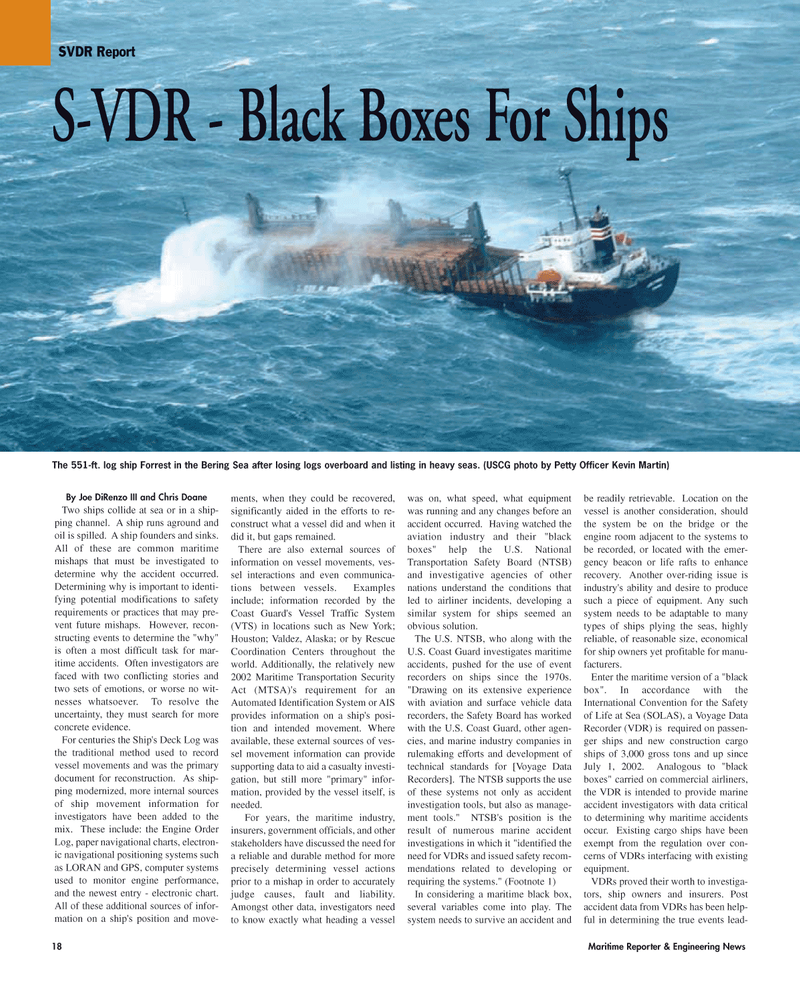

The 551-ft. log ship Forrest in the Bering Sea after losing logs overboard and listing in heavy seas. (USCG photo by Petty Officer Kevin Martin)

MR JANUARY2006 #3 (17-24).qxd 1/3/2006 3:06 PM Page 18

17

17

19

19