Page 64: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (June 2, 2010)

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of June 2, 2010 Maritime Reporter Magazine

64 Maritime Reporter & Engineering News 2010 WORLD YEARBOOK THE ARCTIC

From the first voyages across the North

Atlantic, icebergs have been a major threat to shipping interests. The most fa- mous disaster was the sinking of the

RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. On her maiden voyage from Southampton to

New York, the vessel struck an iceberg approximately 400 nautical miles south of Newfoundland, Canada. Less than 3 hours later the Titanic sank beneath the surface, taking with her over 1500 pas- sengers.

There were many other ship-iceberg ac- cidents before the Titanic. On April 14, 1897, the French Brigt Vaillant collided with an iceberg near St. Pierre (French territory south of Newfoundland). Sev- enty-eight lives were lost with only four survivors who were picked up seven days later (Hill, 2005). On February 19, 1893, the SS Naronic struck an iceberg in a snowstorm across the Grand Banks, killing all 74 people onboard (Hill, 2005).

More recently, on March 18, 2000, the

Shrimp Trawler BCM Atlantic sank ap- proximately 240 km east of Goose Bay,

Labrador. The vessel struck a bergy bit (small iceberg) while in heavy snow.

Everyone on the vessel was rescued safely (Hill, 2005).

However, it was the sinking of the Ti- tanic that spurred the global marine com- munity to create an iceberg patrol. The first ice patrol was sent by the United

States Coast Guard in 1913 utilizing two

Cutters. From then on, the International

Ice Patrol (IIP) has been providing pru- dent iceberg information to vessels tran- siting the North Atlantic shipping lanes.

Icebergs Defined

An iceberg is a large piece of ice that has broken away (or calved) from a gla- cier and is at least 5m above sea level.

Icebergs are categorized by size from very large (over 75 meters high and 200 meters wide) to growler (less than 1 meter high and less than 5 meters wide).

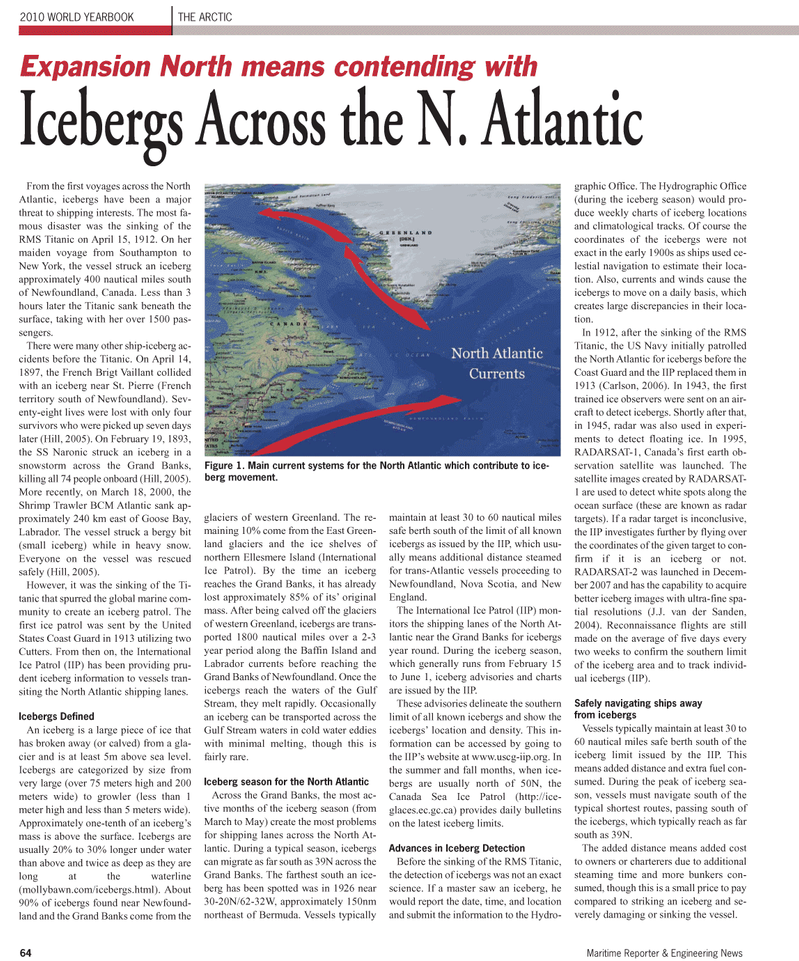

Approximately one-tenth of an iceberg’s mass is above the surface. Icebergs are usually 20% to 30% longer under water than above and twice as deep as they are long at the waterline (mollybawn.com/icebergs.html). About 90% of icebergs found near Newfound- land and the Grand Banks come from the glaciers of western Greenland. The re- maining 10% come from the East Green- land glaciers and the ice shelves of northern Ellesmere Island (International

Ice Patrol). By the time an iceberg reaches the Grand Banks, it has already lost approximately 85% of its’ original mass. After being calved off the glaciers of western Greenland, icebergs are trans- ported 1800 nautical miles over a 2-3 year period along the Baffin Island and

Labrador currents before reaching the

Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Once the icebergs reach the waters of the Gulf

Stream, they melt rapidly. Occasionally an iceberg can be transported across the

Gulf Stream waters in cold water eddies with minimal melting, though this is fairly rare.

Iceberg season for the North Atlantic

Across the Grand Banks, the most ac- tive months of the iceberg season (from

March to May) create the most problems for shipping lanes across the North At- lantic. During a typical season, icebergs can migrate as far south as 39N across the

Grand Banks. The farthest south an ice- berg has been spotted was in 1926 near 30-20N/62-32W, approximately 150nm northeast of Bermuda. Vessels typically maintain at least 30 to 60 nautical miles safe berth south of the limit of all known icebergs as issued by the IIP, which usu- ally means additional distance steamed for trans-Atlantic vessels proceeding to

Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and New

England.

The International Ice Patrol (IIP) mon- itors the shipping lanes of the North At- lantic near the Grand Banks for icebergs year round. During the iceberg season, which generally runs from February 15 to June 1, iceberg advisories and charts are issued by the IIP.

These advisories delineate the southern limit of all known icebergs and show the icebergs’ location and density. This in- formation can be accessed by going to the IIP’s website at www.uscg-iip.org. In the summer and fall months, when ice- bergs are usually north of 50N, the

Canada Sea Ice Patrol (http://ice- glaces.ec.gc.ca) provides daily bulletins on the latest iceberg limits.

Advances in Iceberg Detection

Before the sinking of the RMS Titanic, the detection of icebergs was not an exact science. If a master saw an iceberg, he would report the date, time, and location and submit the information to the Hydro- graphic Office. The Hydrographic Office (during the iceberg season) would pro- duce weekly charts of iceberg locations and climatological tracks. Of course the coordinates of the icebergs were not exact in the early 1900s as ships used ce- lestial navigation to estimate their loca- tion. Also, currents and winds cause the icebergs to move on a daily basis, which creates large discrepancies in their loca- tion.

In 1912, after the sinking of the RMS

Titanic, the US Navy initially patrolled the North Atlantic for icebergs before the

Coast Guard and the IIP replaced them in 1913 (Carlson, 2006). In 1943, the first trained ice observers were sent on an air- craft to detect icebergs. Shortly after that, in 1945, radar was also used in experi- ments to detect floating ice. In 1995,

RADARSAT-1, Canada’s first earth ob- servation satellite was launched. The satellite images created by RADARSAT- 1 are used to detect white spots along the ocean surface (these are known as radar targets). If a radar target is inconclusive, the IIP investigates further by flying over the coordinates of the given target to con- firm if it is an iceberg or not.

RADARSAT-2 was launched in Decem- ber 2007 and has the capability to acquire better iceberg images with ultra-fine spa- tial resolutions (J.J. van der Sanden, 2004). Reconnaissance flights are still made on the average of five days every two weeks to confirm the southern limit of the iceberg area and to track individ- ual icebergs (IIP).

Safely navigating ships away from icebergs

Vessels typically maintain at least 30 to 60 nautical miles safe berth south of the iceberg limit issued by the IIP. This means added distance and extra fuel con- sumed. During the peak of iceberg sea- son, vessels must navigate south of the typical shortest routes, passing south of the icebergs, which typically reach as far south as 39N.

The added distance means added cost to owners or charterers due to additional steaming time and more bunkers con- sumed, though this is a small price to pay compared to striking an iceberg and se- verely damaging or sinking the vessel.

Expansion North means contending with

Icebergs Across the N. Atlantic

Figure 1. Main current systems for the North Atlantic which contribute to ice- berg movement.

63

63

65

65