Page 38: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (February 2014)

Cruise Shipping Edition

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of February 2014 Maritime Reporter Magazine

38 Maritime Reporter & Engineering News • FEBRUARY 2014

MR’S 75TH ANNIVERSARY

Another example of where Gibbs took existing technologies to an extreme is

Safety. “Gibbs was a fanatic about safe- ty, he had an absolute paranoia about fi re,” says Norris, noting that the naval architect was deeply affected by the 1934 burning of the S.S. Morro Castle, which killed 137 passengers and crew.

The disaster spawned improvements in ship safety overall, but Gibbs left noth- ing to chance, going well beyond all the safety standards of the day.

Everything had to be fi reproof right down to the paint and the bedding, lead- ing to the use of chemical retardants, fi - berglass and Maronite, panels encasing an asbestos layer that coated the ship.

He famously banned wood from the structure, “except for the piano and the chopping block.” Not that Gibbs didn’t try to get Steinway & Sons to build an aluminum piano. Instead, Steinway proved to Gibbs his pianos would not burn by pouring gas on top and light one up in a demonstration.

Other safety features included more lifeboats and rafts than the ship need- ed, and a remotely controlled from the bridge system that would close doors in the event of a fi re, containing damage.

All combined, the super-secret hull design, compact state-of-the-art en- gines, 250,000 HP, boiler system with its super-heated dry steam, the fi ve- bladed propellers, the super lightweight all-aluminum super structure, the un- heard of attention to numerous safety measures deployed within and about the ship and it’s celebrity clientele – are just part of what created a legend. But it wasn’t enough to fi ght the continued march of technological progress.

Up, Up and Away

In a nutshell, commercial air travel, which debuted in 1958, and progres- sively improved and expanded through the ‘60s, killed the trans-Atlantic pas- senger liners. As Bob Sturm, another former engineer on the ship notes, “Six hours on a plane beats 4.5 days to New

York or France.” Passengers voted with their feet, especially businessmen, for whom time is money.

Rising fuel costs and restless unions on the heavily staffed ships took their toll as well. “She consumed 700 tons a day in fuel. When it’s $2 a barrel it doesn’t matter, but in the end fuel costs began to escalate pretty dramatically,” said Norris. Tug strikes forced Commo- dore Anderson on more than one occa- sion to pilot his ship into the dock by himself.

One by one, passenger liners started dropping by the wayside. By 1969, the

United States was sent home to dry dock in Norfolk, Va. in November; af- ter a mere 17 years of service, she never sailed again.

Initially, she was mothballed by

MARAD. Once the ship was declassi- fi ed, the agency divested itself of the now white whale. After passing through multiple hands, being dragged to vari- ous ports and suffering several waves of gutting, the ship ended up in the hands of the Norwegian Cruise line, which had hoped to restore it back to a work- ing ship. Ultimately the ship was sold in 2011 to the Conservancy, notably at a lower prices than could have been got- ten from ship scrapper, fi nanced with a donation from Philadelphia philan- thropist H. F. Lenfest, a fi nance pack- age that included two years of monthly maintenance fees, funds which today are gone. Today, the group relies on donations and revenue from the sale of precious metals in the ship to cover the $65,000 to 80,000/month in dock- age, insurance, security and other costs while it tries to land a development deal to secure a future for the ship.

But the clock is ticking. To keep the ship safe until a deal can be worked out, ‘We need money, money, money,” says the Conservancy’s Gibbs.

An American Icon

Half the battle in raising funds lies is the diffi culty in trying to articulate to a modern audience why The Big Ship is so important, laments Anderson, who sailed on the ship as a teen. “Most cruise ships today are more like fl oat- ing hotels. There was no transatlantic air service in the ‘50s and most of the ‘60s. The big liners were used to trans- port not just vacationers, but business men and immigrants – it’s an important distinction that is completely lost on people today. It was a ship with a real purpose.

A dual purpose actually, although the ship only came close once to function- ing as a military transport, when it put on standby during the Cuban missile crisis.

Conservancy members and fans of the

Big U say the ship should be preserved as a symbol of American strength and technological know-how, as well as one of the few remaining examples of a once proud U.S.-fl agged merchant marine. “This country has lost its con- nection with its maritime history and

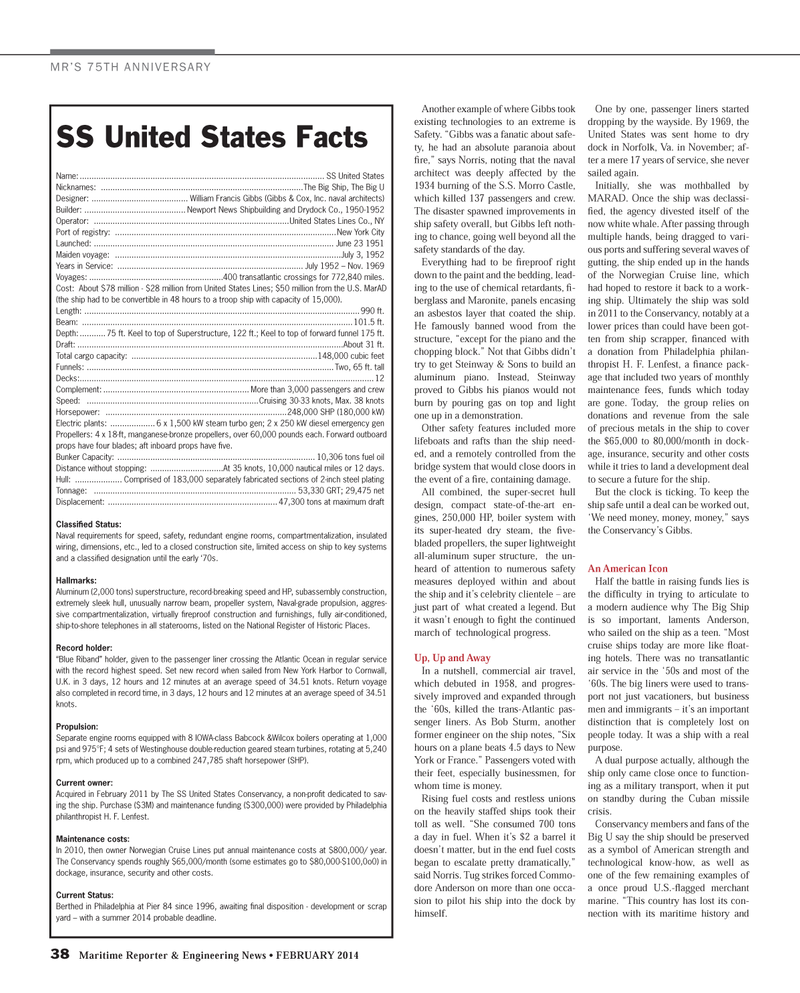

SS United States Facts

Name: ........................................................................................................ SS United States

Nicknames: ......................................................................................The Big Ship, The Big U

Designer: ......................................... William Francis Gibbs (Gibbs & Cox, Inc. naval architects)

Builder: ........................................... Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co., 1950-1952

Operator: ...................................................................................United States Lines Co., NY

Port of registry: ..............................................................................................New York City

Launched: ...................................................................................................... June 23 1951

Maiden voyage: ................................................................................................July 3, 1952

Years in Service: ............................................................................... July 1952 – Nov. 1969

Voyages: .........................................................400 transatlantic crossings for 772,840 miles.

Cost: About $78 million - $28 million from United States Lines; $50 million from the U.S. MarAD (the ship had to be convertible in 48 hours to a troop ship with capacity of 15,000).

Length: .....................................................................................................................990 ft.

Beam: ...................................................................................................................101.5 ft.

Depth: ........... 75 ft. Keel to top of Superstructure, 122 ft.; Keel to top of forward funnel 175 ft.

Draft: .................................................................................................................About 31 ft.

Total cargo capacity: ...............................................................................148,000 cubic feet

Funnels: .........................................................................................................Two, 65 ft. tall

Decks: .............................................................................................................................12

Complement: .............................................................. More than 3,000 passengers and crew

Speed: .........................................................................Cruising 30-33 knots, Max. 38 knots

Horsepower: .............................................................................248,000 SHP (180,000 kW)

Electric plants: ................... 6 x 1,500 kW steam turbo gen; 2 x 250 kW diesel emergency gen

Propellers: 4 x 18-ft, manganese-bronze propellers, over 60,000 pounds each. Forward outboard props have four blades; aft inboard props have fi ve.

Bunker Capacity: .................................................................................... 10,306 tons fuel oil

Distance without stopping: ...............................At 35 knots, 10,000 nautical miles or 12 days.

Hull: .................... Comprised of 183,000 separately fabricated sections of 2-inch steel plating

Tonnage: ...................................................................................... 53,330 GRT; 29,475 net

Displacement: ........................................................................ 47,300 tons at maximum draft

Classifi ed Status:

Naval requirements for speed, safety, redundant engine rooms, compartmentalization, insulated wiring, dimensions, etc., led to a closed construction site, limited access on ship to key systems and a classifi ed designation until the early ‘70s.

Hallmarks:

Aluminum (2,000 tons) superstructure, record-breaking speed and HP, subassembly construction, extremely sleek hull, unusually narrow beam, propeller system, Naval-grade propulsion, aggres- sive compartmentalization, virtually fi reproof construction and furnishings, fully air-conditioned, ship-to-shore telephones in all staterooms, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Record holder: “Blue Riband” holder, given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest speed. Set new record when sailed from New York Harbor to Cornwall,

U.K. in 3 days, 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots. Return voyage also completed in record time, in 3 days, 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots.

Propulsion:

Separate engine rooms equipped with 8 IOWA-class Babcock &Wilcox boilers operating at 1,000 psi and 975°F; 4 sets of Westinghouse double-reduction geared steam turbines, rotating at 5,240 rpm, which produced up to a combined 247,785 shaft horsepower (SHP).

Current owner:

Acquired in February 2011 by The SS United States Conservancy, a non-profi t dedicated to sav- ing the ship. Purchase ($3M) and maintenance funding ($300,000) were provided by Philadelphia philanthropist H. F. Lenfest.

Maintenance costs:

In 2010, then owner Norwegian Cruise Lines put annual maintenance costs at $800,000/ year.

The Conservancy spends roughly $65,000/month (some estimates go to $80,000-$100,0o0) in dockage, insurance, security and other costs.

Current Status:

Berthed in Philadelphia at Pier 84 since 1996, awaiting fi nal disposition - development or scrap yard – with a summer 2014 probable deadline.

MR #2 (32-41).indd 38 2/3/2014 10:26:55 AM

37

37

39

39