Page 24: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (August 2014)

Shipyard Edition

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of August 2014 Maritime Reporter Magazine

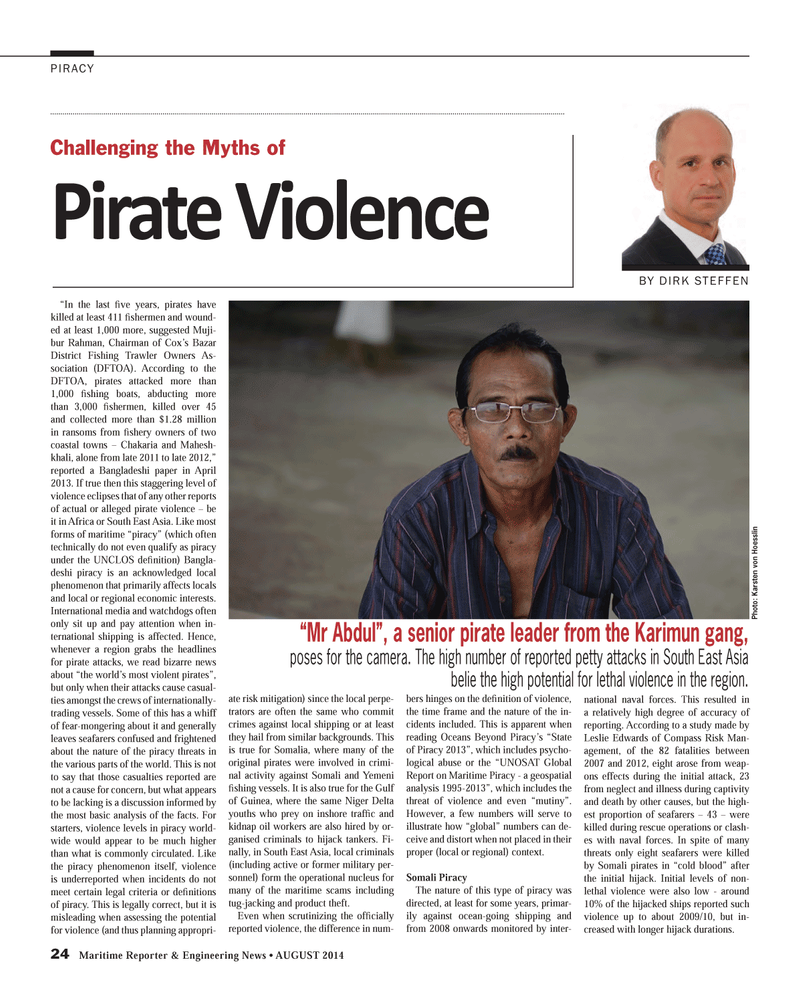

24 Maritime Reporter & Engineering News ? AUGUST 2014 PIRACY ?In the last Þ ve years, pirates have killed at least 411 Þ shermen and wound- ed at least 1,000 more, suggested Muji-bur Rahman, Chairman of Cox?s Bazar District Fishing Trawler Owners As- sociation (DFTOA). According to the DFTOA, pirates attacked more than 1,000 Þ shing boats, abducting more than 3,000 Þ shermen, killed over 45 and collected more than $1.28 million in ransoms from Þ shery owners of two coastal towns ? Chakaria and Mahesh-khali, alone from late 2011 to late 2012,? reported a Bangladeshi paper in April 2013. If true then this staggering level of violence eclipses that of any other reports of actual or alleged pirate violence ? be it in Africa or South East Asia. Like most forms of maritime ?piracy? (which often technically do not even qualify as piracy under the UNCLOS deÞ nition) Bangla- deshi piracy is an acknowledged local phenomenon that primarily affects locals and local or regional economic interests. International media and watchdogs often only sit up and pay attention when in-ternational shipping is affected. Hence, whenever a region grabs the headlines for pirate attacks, we read bizarre news about ?the world?s most violent pirates?, but only when their attacks cause casual-ties amongst the crews of internationally-trading vessels. Some of this has a whiff of fear-mongering about it and generally leaves seafarers confused and frightened about the nature of the piracy threats in the various parts of the world. This is not to say that those casualties reported are not a cause for concern, but what appears to be lacking is a discussion informed by the most basic analysis of the facts. For starters, violence levels in piracy world-wide would appear to be much higher than what is commonly circulated. Like the piracy phenomenon itself, violence is underreported when incidents do not meet certain legal criteria or deÞ nitions of piracy. This is legally correct, but it is misleading when assessing the potential for violence (and thus planning appropri-ate risk mitigation) since the local perpe-trators are often the same who commit crimes against local shipping or at least they hail from similar backgrounds. This is true for Somalia, where many of the original pirates were involved in crimi-nal activity against Somali and Yemeni Þ shing vessels. It is also true for the Gulf of Guinea, where the same Niger Delta youths who prey on inshore trafÞ c and kidnap oil workers are also hired by or- ganised criminals to hijack tankers. Fi-nally, in South East Asia, local criminals (including active or former military per- sonnel) form the operational nucleus for many of the maritime scams including tug-jacking and product theft.Even when scrutinizing the ofÞ cially reported violence, the difference in num- bers hinges on the deÞ nition of violence, the time frame and the nature of the in-cidents included. This is apparent when reading Oceans Beyond Piracy?s ?State of Piracy 2013?, which includes psycho-logical abuse or the ?UNOSAT Global Report on Maritime Piracy - a geospatial analysis 1995-2013?, which includes the threat of violence and even ?mutiny?. However, a few numbers will serve to illustrate how ?global? numbers can de-ceive and distort when not placed in their proper (local or regional) context.Somali PiracyThe nature of this type of piracy was directed, at least for some years, primar- ily against ocean-going shipping and from 2008 onwards monitored by inter- national naval forces. This resulted in a relatively high degree of accuracy of reporting. According to a study made by Leslie Edwards of Compass Risk Man-agement, of the 82 fatalities between 2007 and 2012, eight arose from weap-ons effects during the initial attack, 23 from neglect and illness during captivity and death by other causes, but the high-est proportion of seafarers ? 43 ? were killed during rescue operations or clash-es with naval forces. In spite of many threats only eight seafarers were killed by Somali pirates in ?cold blood? after the initial hijack. Initial levels of non-lethal violence were also low - around 10% of the hijacked ships reported such violence up to about 2009/10, but in-creased with longer hijack durations.Pirate Violence Challenging the Myths of BY DIRK STEFFEN ?Mr Abdul?, a senior pirate leader from the Karimun gang, poses for the camera. The high number of reported petty attacks in South East Asia belie the high potential for lethal violence in the region. Photo: Karsten von Hoesslin MR #8 (18-25).indd 24MR #8 (18-25).indd 248/1/2014 11:17:48 AM8/1/2014 11:17:48 AM

23

23

25

25