Page 32: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (May 2017)

The Marine Propulsion Edition

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of May 2017 Maritime Reporter Magazine

Thought Leadership on Cyber Security

Hyper Connectivity: The Risks and Rewards

By John Jorgensen,

Chief Scientist,

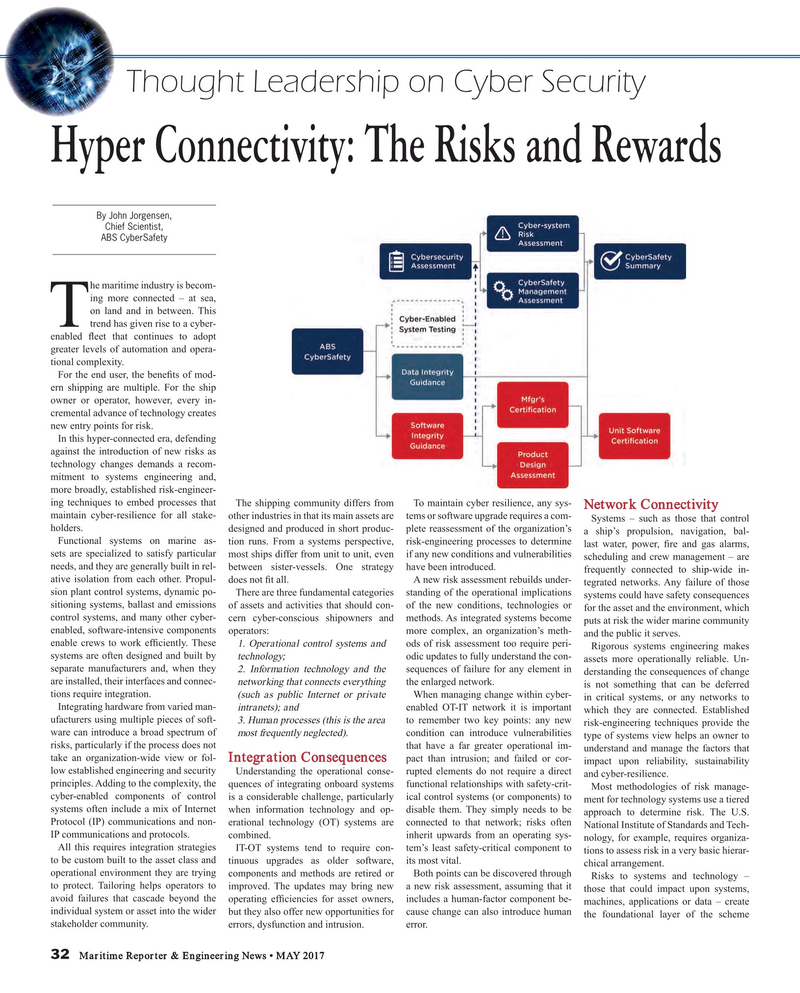

ABS CyberSafety he maritime industry is becom- ing more connected – at sea, on land and in between. This

Ttrend has given rise to a cyber- enabled ? eet that continues to adopt greater levels of automation and opera- tional complexity.

For the end user, the bene? ts of mod- ern shipping are multiple. For the ship owner or operator, however, every in- cremental advance of technology creates new entry points for risk.

In this hyper-connected era, defending against the introduction of new risks as technology changes demands a recom- mitment to systems engineering and, more broadly, established risk-engineer- ing techniques to embed processes that The shipping community differs from To maintain cyber resilience, any sys-

Network Connectivity maintain cyber-resilience for all stake- other industries in that its main assets are tems or software upgrade requires a com-

Systems – such as those that control holders. designed and produced in short produc- plete reassessment of the organization’s a ship’s propulsion, navigation, bal-

Functional systems on marine as- tion runs. From a systems perspective, risk-engineering processes to determine last water, power, ? re and gas alarms, sets are specialized to satisfy particular most ships differ from unit to unit, even if any new conditions and vulnerabilities scheduling and crew management – are needs, and they are generally built in rel- between sister-vessels. One strategy have been introduced. frequently connected to ship-wide in- ative isolation from each other. Propul- does not ? t all. A new risk assessment rebuilds under- tegrated networks. Any failure of those sion plant control systems, dynamic po-

There are three fundamental categories standing of the operational implications systems could have safety consequences sitioning systems, ballast and emissions of assets and activities that should con- of the new conditions, technologies or for the asset and the environment, which control systems, and many other cyber- cern cyber-conscious shipowners and methods. As integrated systems become puts at risk the wider marine community enabled, software-intensive components operators: more complex, an organization’s meth- and the public it serves.

enable crews to work ef? ciently. These 1. Operational control systems and ods of risk assessment too require peri-

Rigorous systems engineering makes systems are often designed and built by technology; odic updates to fully understand the con- assets more operationally reliable. Un- separate manufacturers and, when they 2. Information technology and the sequences of failure for any element in derstanding the consequences of change are installed, their interfaces and connec- networking that connects everything the enlarged network.

is not something that can be deferred tions require integration. (such as public Internet or private When managing change within cyber- in critical systems, or any networks to

Integrating hardware from varied man- intranets); and enabled OT-IT network it is important which they are connected. Established ufacturers using multiple pieces of soft- 3. Human processes (this is the area to remember two key points: any new risk-engineering techniques provide the ware can introduce a broad spectrum of most frequently neglected). condition can introduce vulnerabilities type of systems view helps an owner to risks, particularly if the process does not that have a far greater operational im- understand and manage the factors that take an organization-wide view or fol- pact than intrusion; and failed or cor-

Integration Consequences impact upon reliability, sustainability low established engineering and security Understanding the operational conse- rupted elements do not require a direct and cyber-resilience. principles. Adding to the complexity, the quences of integrating onboard systems functional relationships with safety-crit-

Most methodologies of risk manage- cyber-enabled components of control is a considerable challenge, particularly ical control systems (or components) to ment for technology systems use a tiered systems often include a mix of Internet when information technology and op- disable them. They simply needs to be approach to determine risk. The U.S.

Protocol (IP) communications and non- erational technology (OT) systems are connected to that network; risks often National Institute of Standards and Tech-

IP communications and protocols. combined. inherit upwards from an operating sys- nology, for example, requires organiza-

All this requires integration strategies IT-OT systems tend to require con- tem’s least safety-critical component to tions to assess risk in a very basic hierar- to be custom built to the asset class and tinuous upgrades as older software, its most vital. chical arrangement.

operational environment they are trying components and methods are retired or Both points can be discovered through

Risks to systems and technology – to protect. Tailoring helps operators to improved. The updates may bring new a new risk assessment, assuming that it those that could impact upon systems, avoid failures that cascade beyond the operating ef? ciencies for asset owners, includes a human-factor component be- machines, applications or data – create individual system or asset into the wider but they also offer new opportunities for cause change can also introduce human the foundational layer of the scheme stakeholder community. errors, dysfunction and intrusion. error. 32 Maritime Reporter & Engineering News • MAY 2017

MR #5 (26-33).indd 32 MR #5 (26-33).indd 32 5/3/2017 8:19:18 PM5/3/2017 8:19:18 PM

31

31

33

33