Interview: RDML Gallaudet Steers NOAA’s Path Toward Uncrewed Maritime Systems

NOAA and the United States Navy recently signed a new agreement to jointly expand the development and operations of unmanned maritime systems in the nation’s coastal and world’s ocean waters. Headlining MTR’s Autonomous Vehicle Operations coverage this month is our interview with retired Navy Rear Adm. Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., assistant secretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere and deputy NOAA administrator, for insights on the direction and pace of the use of unmanned maritime systems for NOAA’s future.

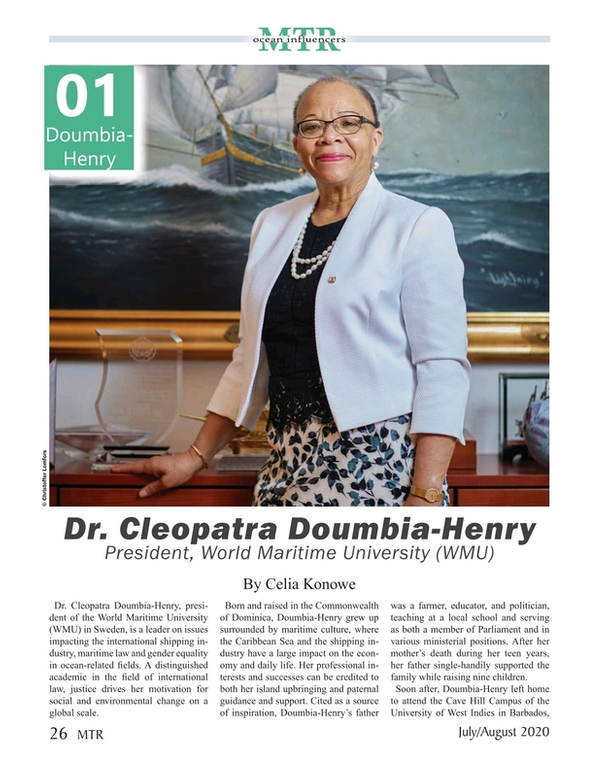

When did you realize that yours would be a career dedicated to Oceanography?

I grew up in Southern California and hit the beach a lot. My dad was a naval officer so that brought me in contact with the service and working on the sea. As long as I can remember I always wanted to study the ocean and have a career on it.

Using the start of your career to today as bookends, put in perspective how the focus of “ocean issues” has changed the most.

In the 1980s when I was starting my ocean career, ocean issues were not as big as they are today. The areas that I’ve seen advance the most can be categorized in three main areas:

- • Ocience Science & Technology: understanding has accelerated exponentially via technology. The things we know now about our ocean and its impact on our planet and climate are light years ahead of what we knew when I started.

- • A growing appreciation of ocean health and conservation by the public. There’s an increased awareness about the dependence of our security and our economy on the oceans. People simply care a lot more (today).

- • A growing awareness of the necessity for sustainable use of our oceans, which includes everything from fisheries, to marine transportation, to critical minerals and pharmaceuticals.

Using that same time frame, put in perspective the evolution of unmanned maritime systems as you see it.

To start, just this week we’ve decided we are going to move from the word ‘unmanned’ to ‘uncrewed.’ I know ‘unmanned’ is an industry standard, but that’s changing for all the reasons that it should: we have a lot of bright young women that are advancing these technologies. Looking at the evolution, when I first went to Scripps as a Masters student in 1989, the state-of-the-art was side scan sonar being towed behind ships, or the deep-tow that the Scripps marine physical labs used to conduct deep bathymetric surveys and exploration with cameras.

That was it.

Today we have remotely operated vehicles rated to the same depth with HD optical and acoustic sensors, and then we have a plethora of UUVs, AUVs, ASVs, Hybrids – the collection capabilities of some of our multibeam sonars on our ships is like HD TV compared to what we had in the 80s. (The technological advances are) great to help us understand our oceans, (but) now you see it is more than simply a science exercise, as we are using this commercially for oil and gas exploration and for defense.

Please give an overview of the size and shape of uncrewed maritime systems currently in the ‘fleet’ or at the disposal or NOAA, and discuss how you see this expanding and evolving in the future.

There is a rich array of capabilities. In my agency, we have a fleet of about 100 platforms; with our partners – primarily the Navy – we have a fleet of about 300 to 500. It offers a range of capabilities from long endurance to deep diving to surface vessels and gliders. We partnered with (iXblue’s) DRiX, which is a USV with a wave piercing bow capable of 14 knots. I would not have dreamed that we could collect IHO Order One bathymetry with a USV at that speed in significant sea states, but it can. Then we’re advancing our deep diving 6000m ROV capabilities and we’re going to move more into AUV applications too. We have developed an unmanned systems strategy – soon to be renamed ‘uncrewed’ – that looks at the dramatic acceleration and expansion of our applications of these systems. We rely heavily on partnerships, and the goal is to make all of our ships ‘Mother Ships’ of these types of systems, to include uncrewed air systems, too.

“We partnered with (iXblue’s) DRiX, which is a USV with a wave piercing bow capable of 14 knots. I would not have dreamed that we could collect IHO Order One bathymetry with a USV at that speed in significant sea states, but it can.”

“We partnered with (iXblue’s) DRiX, which is a USV with a wave piercing bow capable of 14 knots. I would not have dreamed that we could collect IHO Order One bathymetry with a USV at that speed in significant sea states, but it can.”

RDML Tim Gallaudet, NOAA (Photo: iXblue)

The impetus for this interview was the recent agreement between NOAA and the U.S. Navy “to jointly expand the development and operations of unmanned maritime systems in the nation’s coastal and world’s ocean waters.” Why is this agreement significant, and perhaps more importantly, why wasn’t this type of agreement already in place?

NOAA has been working with the Navy, in fact they’ve been working with the Navy since I was in the Navy as the head of all Navy oceanography assets. Growing our autonomous systems was a goal then, and I developed a similar strategy to expand our operations and research in that realm. This new re-signing of an annex of a broader MOU is to implement a recent act signed by the president – the CENOTE Act or the Commercial Engagement Through Ocean Technology Act – that has specific provisions about the Navy and NOAA partnering, leveraging the Navy’s infrastructure and best practices as well as other assets on the Gulf Coast. This includes a new Ocean Enterprise facility in the Port of Gulfport which is being built, and is intended to be our base of operations for uncrewed maritime systems. This partnership with the Navy is one of about a dozen that we have signed or will sign in the coming months (with commercial, philanthropic and academic organizations) – surrounding Ocean S&T, ocean exploration or autonomous systems. It’s exciting to see how we’re leveraging all that’s out there in a smart way.

How does NOAA use uncrewed maritime systems today, and perhaps more importantly, how do you see the use of UMS expanding in the near- and long-term?

We are already conducting a wide array of activity, from marine mammal and fishery surveys using aerial drones; coastal mapping surveys with aerial and surface drones (to name but a few). Those are important because we have a new national strategy to map the U.S. EEZ. All in all, we are already using these tools widely, but not exclusively. Increased use of autonomy for every NOAA mission needs to become the standard.

Samples Study: NOAA’s Megan Cromwell retrieves as sample collecting during a dive off Puerto Rico. Photo: NOAA

Samples Study: NOAA’s Megan Cromwell retrieves as sample collecting during a dive off Puerto Rico. Photo: NOAA

When you look at the uncrewed marine systems today, what do you see as the number one technical hurdle to make these systems as prevalent as we’ve seen the systems become on land and in the air?

The ocean is a difficult place to work. I had the pleasure to meet Scott Carpenter, who has the distinction of being an astronaut and an aquanaut. I asked him to compare space to the ocean, and he said: ‘Space is glorious, it’s bright and shiny; the ocean is cold, dark and hard.’ But we’re overcoming (some of the challenges) with materials science to prevent corrosion; advances in battery technology to extend endurance. Jim Bellingham has this great hybrid AUV that we’re working with the Alaska Domain Awareness Center to deploy this 600-nm rated Hybrid AUV in the Arctic.

Gearing Up to See Below: Jan Albiez, an engineer with Kraken Robotics, inspects Kraken’s SeaVision, a compact underwater laser imaging system that was attached to a NOAA remotely operated vehicle for testing in 2019. NOAA entered into a formal joint research and development partnership with Kraken to combine Kraken’s technology and desire to design and manufacture advanced mapping and ocean exploration systems with NOAA’s ability to test and establish functionality while at sea. Photos: NOAA

Gearing Up to See Below: Jan Albiez, an engineer with Kraken Robotics, inspects Kraken’s SeaVision, a compact underwater laser imaging system that was attached to a NOAA remotely operated vehicle for testing in 2019. NOAA entered into a formal joint research and development partnership with Kraken to combine Kraken’s technology and desire to design and manufacture advanced mapping and ocean exploration systems with NOAA’s ability to test and establish functionality while at sea. Photos: NOAA

Looking at the full scope of responsibility under your command, can you distill what you count as the top three or four advantages that come with a larger, more capable and connected uncrewed maritime system fleet?

As we expand this fleet of ours and apply them to all of our missions, performance is one. It used to be that you couldn’t get the quality, but that has changed and you can get nearly the same quality of data from autonomous system. It is efficiency, too. We don’t even need a ship with some of these systems, and they are particularly valuable in doing the dull, dirty and dangerous jobs. Just this last month, because of COVID our ships were pier-side and we had three major uncrewed system efforts to go perform missions and fill a collection gap that we had. We sent out saildrones to collect acoustic data for a pollock survey in Alaska, which is one of the most economically critical fisheries in our country; data which is essential to manage that fishery. We conducted an Alaska North Slope coastal survey with the same system, part of our Alaska mapping strategy. And then as the hurricane season started, we deployed with the Navy about a dozen gliders to sample the water column and the temperature near the surface, because that is a critical parameter to better forecast hurricane intensification. With these systems we are better able to predict, to save lives and property. All of this was done under COVID protocols.

In your career, what do you count as the number one technology evolution that has helped oceanographers to do their business more safely and efficiently.

I think technology is important, applying it smartly, but what I’ve found is the importance of culture. Big government agencies tend to move slow, (because) to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars we have rigorous regulations and policies. But they can be burdensome at allowing rapid change and quick transformation. At NOAA we released six strategies to advance S&T areas: uncrewed systems, artificial intelligence, ‘Omics, cloud, data and crowd sourcing. This was to better foster collaboration among stove piped offices at NOAA. This lays out our collaborative areas, and partnerships are key to this, both with the Navy and private organizations.

Every leadership position has its challenges. What is your biggest challenge?

Resources. We never have enough in our budget for what we want to do. We are addressing the resources piece through the partnerships that I mentioned, allowing us to do a lot more with less, and this agreement with the Navy is a great example.

Meet RDML Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere & Deputy NOAA Administrator

“(My wife Caren) is an inspiration to me, first because she was a Navy diver, and you don’t need to say more. And second, she was a Navy diver as a female during a time when it was not easy. In the late 1980s/early 1990s there was a lot of sexual harassment in the Navy.” RDML Tim Gallaudet, pictured with his wife Caren. Photo Courtesy Tim Gallaudet

“(My wife Caren) is an inspiration to me, first because she was a Navy diver, and you don’t need to say more. And second, she was a Navy diver as a female during a time when it was not easy. In the late 1980s/early 1990s there was a lot of sexual harassment in the Navy.” RDML Tim Gallaudet, pictured with his wife Caren. Photo Courtesy Tim Gallaudet

Rear Admiral Tim Gallaudet is the Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Deputy Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). From 2017-2019 he served as the Acting Undersecretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and NOAA Administrator. Before these assignments, he served for 32 years in the U.S. Navy, completing his service in 2017 as the Oceanographer of the Navy. In his current position, Rear Admiral Gallaudet leads NOAA’s Blue Economy activities that advance marine transportation, sustainable seafood, ocean exploration and mapping, marine tourism and recreation, and coastal resilience. He also directs NOAA’s support to the Administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, oversees NOAA’s Arctic research, operations, and engagement, and is leading the execution of the NOAA science and technology strategies for Artificial Intelligence, Uncrewed Systems, ‘Omics, Cloud, Data, and Citizen Science. Rear Admiral Gallaudet has a Bachelor’s Degree from the U.S. Naval Academy and a Master’s and Doctorate Degree from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, all in oceanography.

Who do you count as the key mentor(s) in your career?

There are too many, and I would do a disservice if I tried to mention just one over the other. I will say the one that I always give credit to is my wife Caren. She was an oceanography major at the Naval Academy in the late 1980s, and we didn’t know each other because she was an underclassman and the classes don’t always mix it up that much. But she became a Navy salvage diver, then left the Navy to go to Scripps, which is where we met. She’s an inspiration to me, first because she was a Navy diver, and you don’t need to say more. And second, she was a Navy diver as a female during a time when it was not easy. In the late 1980s/early 1990s there was a lot of sexual harassment in the Navy, she was subject to it and that’s why she left. To me, I would never want any of my employees or my 3 daughters to experience what she did; I’m committed to women empowerment, as well as diversity and inclusion in general in regards to race or gender. I’m a champion for that because of her. That’s my hero.

If you had best advice for young people thinking of pursuing a career in oceanography, what would it be?

Just do it. Get into the field; it doesn’t matter your skill set or experience base. There is a job for everyone in this community; we’re making discoveries every day, and the well-being of everyone (on the planet) depends on our oceans.

If you had to recommend one good book, what would it be and why?

I’ll recommend two. The first is The Wave by Susan Casey, a great read about oceanography. She’s a great story teller, and probably more than any book I’ve ever read, it makes oceanography look cool. The other book is by a friend of mine and a mentor, Admiral Bill McRaven. He was the Chancellor of University of Texas, he led the Bin Laden raid, and he wrote a book called Make Your Bed. To me this is a must read for any American leader for the examples and lessons it teaches.

Outside of the job, what do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

We are an ocean family, we love to scuba dive, I love to free dive, I was an All-American swimmer and I keep that up with my girls. I surf when I can and we love to boat, I love to fish when my kids let me. Really, anything ocean related, from museums to aquariums, we do for fun. I consider myself lucky to have a job in a field that I love.

NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer in port in Norfolk, Virginia, following the completion of the Windows to the 2019 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019.

NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer in port in Norfolk, Virginia, following the completion of the Windows to the 2019 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019.

Read Interview: RDML Gallaudet Steers NOAA’s Path Toward Uncrewed Maritime Systems in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of July 2020 Marine Technology

Other stories from July 2020 issue

Content

- Underwater Vehicle Propulsion Tech: Tail Shape and Vehicle-Propulsor Performance page: 16

- Charting Terradepth's Big Ambitions in the Unmanned Vehicle Space page: 20

- Interview: RDML Gallaudet Steers NOAA’s Path Toward Uncrewed Maritime Systems page: 26

- Subsea Technology and the New Routes to Residency page: 38

- Hacking 4 Environment: Oceans - Creating Entrepreneurs from Scientists and Students page: 46

- Tracking Climate Change onboard SeaExplorer page: 50