Insights: Contracts are Overrated in Maritime

My company has been around since 1875, and today we actually still do things that were being done in 1875. We still get calls from underwriters to attend on disasters all over the place, and we are still asked to provide values on ships on a moment’s notice.

Moreover, some of the companies that ask us to attend to those issues, in some form or another, also have been around since 1875.

That results in a very smooth operational routine, where we get a call from one of those clients in the middle of the night, we pull our pants on, step into the car and go out to see what is going on. There is no discussion about compensation, there is no discussion about contracts, and there is no discussion about retainers. We simply go out.

We do this not with one or two or three trusted clients; we do this with dozens, if not hundreds, of clients, some of whom may only call once every decade or so. We have no contractual arrangements with any of them. We do the job, send the bill and get paid.

Occasionally somebody calls for the first time and wants us to go on a job and timidly asks if we need a purchase order, or a contract, or a retainer before we can start to move. Today we say: “Send us a quick email that has the various contact info and that simply says you want us to go out to do this thing.” (We used to say send us a telex, and, for a decade or two, we used to tell them to send us a fax.) That email is very helpful because I generally cannot find a pen that works in the middle of the night, and to spell out a foreign sounding name on a bad telephone connection is even more frustrating.

If there is a little more time, I sometimes ask the new client a question first. I ask them if they know where we are based. Sometimes they know and sometimes they don’t, but my answer is effectively the same: “We are located in New Jersey, therefore there is no need for a written contract. We always get paid.” Whether the new client is from Oman, or Virginia, that response always invokes images of the Sopranos, and they chuckle and they send the email and we are on our way.

To the rest of the world this lack of contract may seem scary as hell, and sometimes people ask me if we lose a lot of money to people who do not pay. Weirdly, we rarely encounter a client who does not pay. It is truly rare and those who do not pay end up in a special category within our company. Remember, we are based in New Jersey.

Regardless, many years ago, after a number of those exchanges, I started to ponder the weirdness of the lack of contracts in my company’s operations.

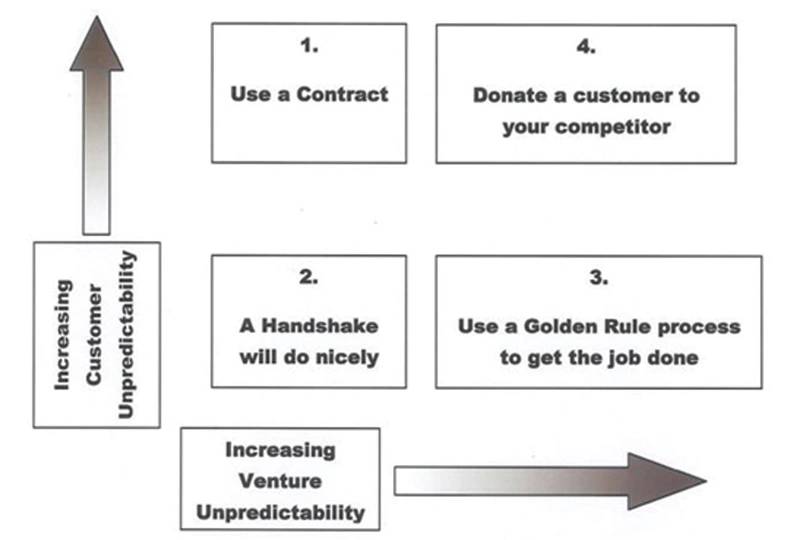

It turns out there is something about contracts that led me to develop this little graph. To me it provided some personal clarity, but it actually has very wide implication and application.

The little graph is shown in figure 1.

In effect there are four quadrants.

Quadrant 1 is a project that has predictability, but you do not know the client. This is where a standard contract may be of help. Hull and Machinery insurance and its associated contract (the policy) is a good example of that. A client in this quadrant may be a midnight call for me, and I may pass on the contract, but our mention of New Jersey actually is a form of a contract. Both parties know what to abstractly expect when the New Jersey Soprano clause is invoked.

Quadrant 2 is a client you know and a project that has high predictability. It is the call in the night where the client knows you will spend a certain number of days that will cost a certain amount of money, but then there will be a communication that further increases project predictability. (In my business that is called a survey.)

Quadrant 3 is a project that has very little predictability with a known client. We occasionally get involved in those projects and then we warn our client that we may be doing a ton of work before we can even figure out if it was worth doing the work. We never have had serious problems with getting paid on those projects. We did not use a contract, but we did have a frank discussion with our client that it may be far from a pleasant financial experience. In those situations, you have to have faith that when the project does not work out the client does not lay the blame on your doorstep. These types of projects are not uncommon in the rest of the world and some very big projects have been accomplished under this approach.

I have never done a deep study of the Nuclear Submarine Nautilus contracting structure, but I am almost certain that there were very many moments where the customer (Hyman Rickover) said to any number of contractors: “Just go give it a shot, we will pay whether it works or not, I just want to get it done.” The pace of the Nautilus Project was so high that it is highly unlikely that there was a lot of contract development for each little step. The project simply ran on faith.

Another example was the agreement between George Washington and the Continental Congress, that he would work without a salary as the leader of the Continental Army, but would have his expenses reimbursed. (I can’t help but try to imagine that negotiation.)

Quadrant 4 is where wisdom really comes into play. This is the type of project where you don’t know the client and don’t know where the project is going to end up. This is where the real risk comes in. A new company may have to take on such clients to grow, and some companies may have to take on such clients to simply survive. I had a business school instructor who defined these customers as the ones you want to send to your competitors. I am not totally sure that is the optimal approach, but it is a simple answer to a complex issue. However, there are businesses where you have to deal with unknown clients on uncertain projects. Salvage is my favorite example, and the salvage industry has developed a solution that is called a No Cure, No Pay or Lloyd’s Open Form contract, where it simply defers the cost resolution to a later stage and relies on an arbitrator. It is not a perfect solution, but it helps both parties at the moment when decisions need to be made.

The really neat part about the graph is that it can also show optimization movement. The trick is to get every one of your projects out of Quadrant 4 and to keep them out of Quadrant 4. The best way to do that is to build faith between you and your client. It is called business reputation, both for you and your client. Faith and reputation do not build in leaps; they build in small steps, many small steps.

This explains why my company uses few contracts. Most of our new client contacts relate to relatively small projects as compared to our company size, and it allows us to test the waters before we get in deeper and allows us to take a risk on new friends we have not yet met. It also has a very important effect on efficiency. Not having to deal with contracts is a significant cost saver and benefits both the service provider and the client. I am not arguing for a world without contracts; what I am arguing is that there are many situations where contracts are not cost effective.

Remarkably, the whole marine industry is based on this type of cost effectiveness, and this is why we live with concepts such as Utmost Good Faith and the burden to provide assistance in time of emergency at sea, and also admire great Captains and Chief Engineers who run great ships and use the concept of “Trust your crew, but don’t forget to verify.”

We have contracts in the marine industry, but the best contracts are deeply standardized (BIMCOs) or are purposely quite simple (LOF). The mark of a novice in the marine industry is a player who insists on novel or complicated contracts and too often we are asked to help them sort things out after things go wrong; on those projects we do occasionally ask for a retainer.

For each column I write, MREN has agreed to make a small donation to an organization of my choice. For this column I nominate the American Salvage Association Educational Committee, which provides awards to young people who do research in marine science and engineering. Salvage is an almost incredible act of good faith on unpredictable projects. http://www.americansalvage.org/education-committee.php

About the Author

Rik van Hemmen is the President of Martin & Ottaway, a marine consulting firm that specializes in the resolution of technical, operational and financial issues in maritime. By training he is an Aerospace and Ocean engineer and has spent the majority of his career in engineering design and forensic engineering.

Read Insights: Contracts are Overrated in Maritime in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 2020 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from April 2020 issue

Content

- COVID-19: Your LMS Can Help You Now More Than Ever page: 12

- USCG Polar Security Cutters: The History and Future page: 22

- Insights: Contracts are Overrated in Maritime page: 24

- Interview: Dr. Dirk Jürgens, Heads of R&D, Voith Turbo Marine page: 26

- Reinauer Group Ramps Up for the Business of Offshore Wind page: 34