Page 20: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (September 1969)

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of September 1969 Maritime Reporter Magazine

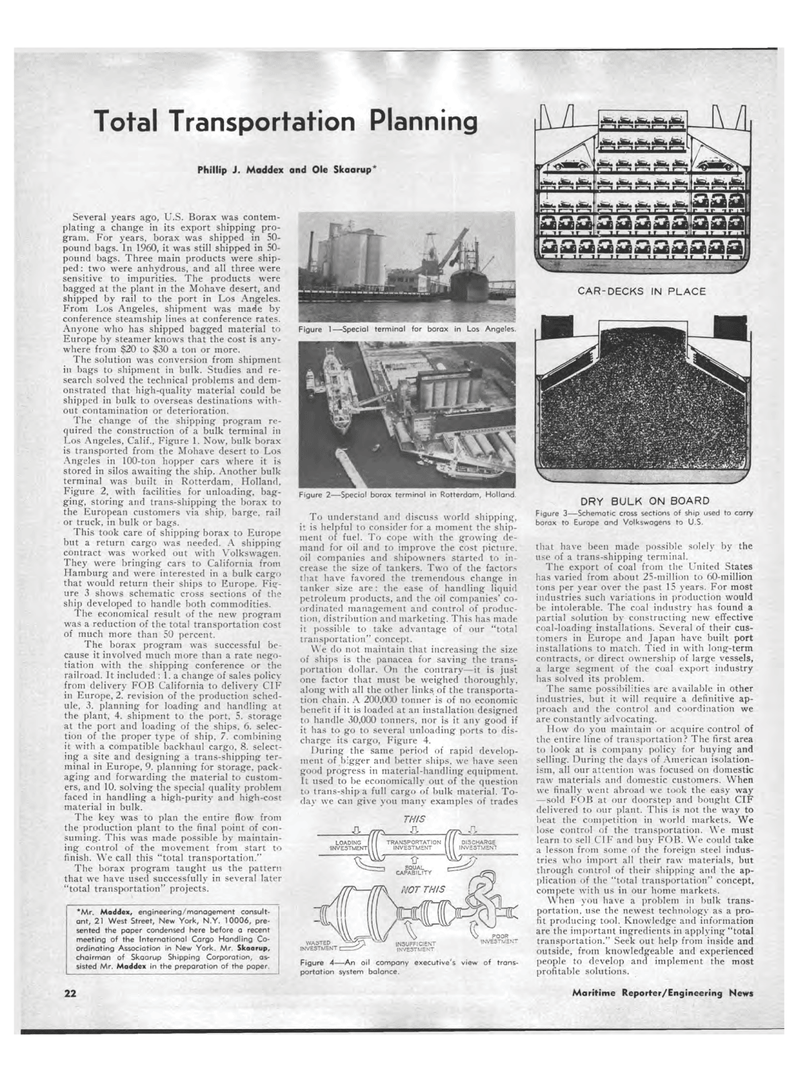

Total Transportation Planning Phillip J. Maddex and Ole Skaarup* Several years ago, U.S. Borax was contem-plating a change in its export shipping pro-gram. For years, borax was shipped in 50-pound bags. In 1960, it was still shipped in 50-pound bags. Three main products were ship-ped : two were anhydrous, and all three were sensitive to impurities. The products were bagged at the plant in the Mohave desert, and shipped by rail to the port in Los Angeles. From Los Angeles, shipment was made by conference steamship lines at conference rates. Anyone who has shipped bagged material to Europe by steamer knows that the cost is any-where from $20 to $30 a ton or more. The solution was conversion from shipment in bags to shipment in bulk. Studies and re-search solved the technical problems and dem-onstrated that high-quality material could be shipped in bulk to overseas destinations with-out contamination or deterioration. The change of the shipping program re-quired the construction of a bulk terminal in Los Angeles, Calif., Figure 1. Now, bulk borax is transported from the Mohave desert to Los Angeles in 100-ton hopper cars where it is stored in silos awaiting the ship. Another bulk-terminal was built in Rotterdam, Holland. Figure 2, with facilities for unloading, bag-ging, storing and trans-shipping the borax to the European customers via ship, barge, rail or truck, in bulk or bags. This took care of shipping borax to Europe but a return cargo was needed. A shipping contract was worked out with Volkswagen. They were bringing cars to California from Hamburg and were interested in a bulk cargo that would return their ships to Europe. Fig-ure 3 shows schematic cross sections of the ship developed to handle both commodities. The economical result of the new program was a reduction of the total transportation cost of much more than 50 percent. The borax program was successful be-cause it involved much more than a rate nego-tiation with the shipping conference or the railroad. It included : 1. a change of sales policy from delivery FOB California to delivery CIF in Europe, 2. revision of the production sched-ule, 3. planning for loading and handling at the plant, 4. shipment to the port. 5. storage at the port and loading of the ships, 6. selec-tion of the proper type of ship, 7. combining it with a compatible backhaul cargo, 8. select-ing a site and designing a trans-shipping ter-minal in Europe, 9. planning for storage, pack-aging and forwarding the material to custom-ers, and 10. solving the special quality problem faced in handling a high-purity and high-cost material in bulk. The key was to plan the entire flow from the production plant to the final point of con-suming. This was made possible by maintain-ing control of the movement from start to finish. We call this "total transportation." The borax program taught us the pattern that we have used successfully in several later "total transportation" projects. *Mr. Maddex, engineering/management consult-ant, 21 West Street, New York, N.Y. 10006, pre-sented the paper condensed here before a recent meeting of the International Cargo Handling Co-ordinating Association in New York. Mr. Skaarup, chairman of Skaarup Shipping Corporation, as-sisted Mr. Maddex in the preparation of the paper. Figure 1?Special terminal for borax in Los Angeles. Figure 2-?Special borax terminal in Rotterdam, Holland. To understand and discuss world shipping, it is helpful to consider for a moment the ship-ment of fuel. To cope with the growing de-mand for oil and to improve the cost picture, oil companies and shipowners started to in-crease the size of tankers. Two of the factors that have favored the tremendous change in tanker size are: the ease of handling liquid petroleum products, and the oil companies' co-ordinated management and control of produc-tion. distribution and marketing. This has made it possible to take advantage of our "total transportation" concept. We do not maintain that increasing the size of ships is the panacea for saving the trans-portation dollar. On the contrary?it is just one factor that must be weighed thoroughly, along with all the other links of the transporta-tion chain. A 200,000 tonner is of no economic benefit if it is loaded at an installation designed to handle 30,000 tonners, nor is it any good if it has to go to several unloading ports to dis-charge its cargo, Figure 4. During the same period of rapid develop-ment of bigger and better ships, we have seen good progress in material-handling equipment. It used to be economically out of the question to trans-ship a full cargo of bulk material. To-day we can give you many examples of trades THIS WASTED INVESTMENT I INSUFFICIENT INVESTMENT CAR-DECKS IN PLACE ? i m m mi , m Figure 4?An oil company executive's view of trans-portation system balance. DRY BULK ON BOARD Figure 3?Schematic cross sections of ship used to carry borax to Europe and Volkswagens to U.S. that have been made possible solely by the use of a trans-shipping terminal. The export of coal from the United States has varied from about 25-million to 60-million tons per year over the past 15 years. For most industries such variations in production would be intolerable. The coal industry has found a partial solution by constructing new effective coal-loading installations. Several of their cus-tomers in Europe and Japan have built port installations to match. Tied in with long-term contracts, or direct ownership of large vessels, a large segment of the coal export industry has solved its problem. The same possibilities are available in other industries, but it will require a definitive ap-proach and the control and coordination we are constantly advocating. How do you maintain or acquire control of the entire line of transportation? The first area to look at is company policy for buying and selling. During the days of American isolation-ism, all our attention was focused on domestic raw materials and domestic customers. When we finally went abroad we took the easy way ?sold FOB at our doorstep and bought ClF delivered to our plant. This is not the way to beat the competition in world markets. We lose control of the transportation. We must learn to sell CIF and buy FOB. We could take a lesson from some of the foreign steel indus-tries who import all their raw materials, but through control of their shipping and the ap-plication of the "total transportation" concept, compete with us in our home markets. When you have a problem in bulk trans-portation. use the newest technology as a pro-fit producing tool. Knowledge and information are the important ingredients in applying "total transportation." Seek out help from inside and outside, from knowledgeable and experienced people to develop and implement the most profitable solutions. 22 Maritime Reporter/Engineering News

19

19

21

21