Page 33: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (October 1999)

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of October 1999 Maritime Reporter Magazine

faster than a barge, and is less percepti- ble to the eye as the plane passes along its trajectory. Both the database and the modeling required to create images from it are therefore more detailed and substantial in river simulation.

Visual recording of the scene is only the first step. Many different visual sequences may unfold, depending on the choices the pilot makes, from coast- ing in the center of the river to ranging dangerously close to the shore. The database and the visual experience must contain both the basis for choice and the consequences of it. It could be said the simulation is the "whole pilot" interact- ing with the "whole river."

When all the data has been assembled, it is modeled by computer from video and photographic imagery to produce the simulation as a visual experience.

ACBL's training at CME has resulted in greater safety of operations as well as a substantial decrease in the cost of fuel and fleet maintenance. CME has applied this technology to rivers for the first time; its training is therefore unique.

CME is also mindful of the dangers of piloting, both on the ocean and the river, since mistakes may result in loss of life or damage to the environment. An

American admiral was once quoted as saying, "On the sea, 8 to 9 of each 10 fatalities are the result of human error."

So, far more destructive than the forces unleashed by nature or technology is human error itself. Training is designed to minimize this.

The most important part of each course is the student's opportunity to pilot the simulator. He stays in the pilot- house for twenty minutes or so, during which time a navigational challenge is slated to occur, which he resolves with- out any instruction or commentary from instructors. Then he goes into another room for discussion and debriefing. "This is where all the real learning occurs," says Dr. Bill Douglas, who directs the Paducah center. "Our stu- dents are not neophytes. They're here not because they wish to learn skills as such, but because they wish to improve.

The Responsible Carrier Program pro- posed by the American Waterways

Operators encourages constant learning and improvement in piloting. Incidents of environmental damage in the past from piloting errors are also an induce- ment to improve."

The simulation and its various data- bases have no definitive boundaries. The sole criterion of effectiveness is whether the experience seems real to the trainee piloting the system. Among effects to be calculated in each instance are variable weather, wind, time of day or night, restrictions of vision, influence of larger development projects like dams, dredg- ing, alteration of river banks, links, smooth versus rocky river bottoms, effects of river stages and flow condi- tions, etc.

In the South American project, one of the earliest sources of such data was

Brian Donohue's trip down the Parana.

Donohue, who directed design of the simulator's databases, boated down the river for two weeks, videofilming and recording digital stills of the twists and turns in the river. To georeference his position, he employed a hand-held device that used the Global Position

System (GPS). This is only visual infor- mation, however. Donohue took some of his hydrodynamic and bathymetric data mentioned previously from published records and navigation charts of local hydrographers; other data is based upon either his notes while traveling or verbal memories of local pilots.

Consequently, some types of data are easier to collect than others. Brazil, for example, requires those who want statis- tics of the river must physically come to the country to receive it.

The Parana and Paraguay in South

America is thus far represented by seven individual databases incorporating con- ditions and densities of traffic as well as sharp turns in the river. The databases also cover towboats, tugboats, barges, and effects of towing.

The hardware includes swing meters

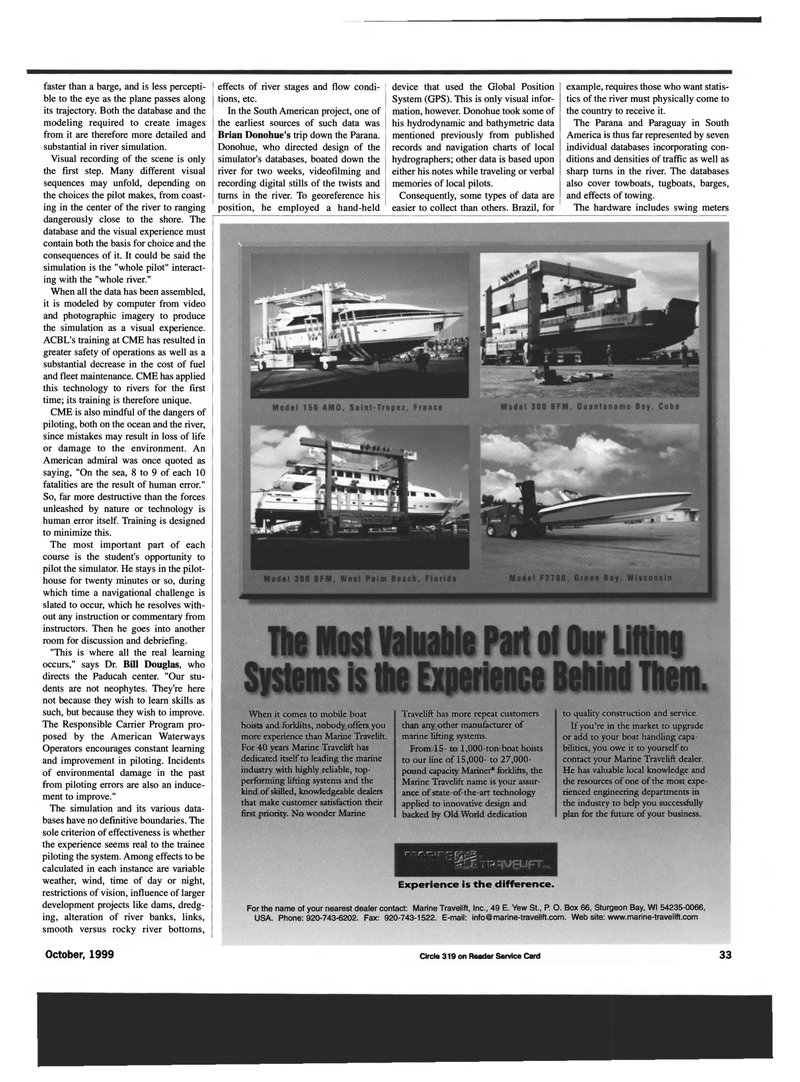

When it comes to mobile boat hoists and forklitts, nobody offers you more experience than Marine Travelift.

For 40 years Marine Travelift has dedicated itself to leading the marine industry with highly reliable, top- performing lifting systems and the kind of skilled, knowledgeable dealers that make customer satisfaction their first priority. No wonder Marine

Travelift has more repeat customers than any other manufacturer of marine lifting systems.

From 15- to 1,000-ton boat hoists to our line of 15,000- to 27,000- pound capacity Mariner® fcrklifts, the

Marine Travelift name is your assur- ance of state-of-the-art technology applied to innovative design and backed by Old World dedication to quality construction and service.

If you're in the market to upgrade or add to your boat handling capa- bilities, you owe it to yourself to contact your Marine Travelift dealer.

He has valuable local knowledge and the resources of one of the most expe- rienced engineering departments in the industry to help you successfully plan for the future of your business. rrmm rrr— ^RStDi

SjlCJi 1 R

Experience is the difference.

For the name of your nearest dealer contact: Marine Travelift, Inc., 49 E. Yew St., P. O. Box 66, Sturgeon Bay, Wl 54235-0066,

USA. Phone:920-743-6202. Fax: 920-743-1522. E-mail: [email protected]. Web site: www.marine-travelift.com

October, 1999 Circle 319 on Reader Service Card 33

32

32

34

34