Page 44: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (November 2005)

The Workboat Annual Edition

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of November 2005 Maritime Reporter Magazine

Gulf of Mexico Resources Guidebook

MARITIME

REPORTER

AND

ENGINEERINGNEWS ic decisions come out of the New Orleans area.

A third Bollinger installation in the area, Quick

Repair on the Harvey Canal, seemed more drenched than damaged. When we dropped in on September 21, engineers at pitchometers were making their precise measurements of propellers, of which a large invento- ry — for which there might soon be a spike in demand — sat orderly on their shelves, to all appearances oblivious to the tempest. There are probably good rea- sons, with an engineer's explanation for why one waterfront locale gets mashed and another barely stained. But until the explanation's given, it all may seem arbitrary, random — or part of a mysterious plan.

That night on TV, a report was given of a predomi- nantly Catholic neighborhood whose lawns were pul- verized, except for the statues of the Virgin. Those stood erect and, like Bollinger's propellers, seeminigly untouched. You can make of that what you will, and plenty of people did.

But over on the Industrial Canal, between the River and the Lake, things ran wild for a time. Many of the same forces that broached the city's levees shifted the architecture and appurtenances of the waterways, leav- ing a world upside-down and backwards. The toll here was against property, and industrial property at that, with nowhere near the flash, the guilt and rhetoric that followed the human and emotional toll in the Ninth

Ward, adjacent. But being less loaded, they permit a cooler appraisal of our place in a world we sometimes think tamed. Too many of our structures and our insti- tutions, it turns out, were built for sunny days.

On Lake Pontchartrain's south end, for example, is a riverboat of sorts — a casino built on a barge and oper- ated by Bally's, but technically capable of navigation — whose reason for being was to part money from fools. One end broke free of its mooring, swinging around from its dock toward the shore, sweeping-up a sailboat or two from the marina next door and using them to cushion its landing on the edge of the parking lot. The lot itself was strewn with yachts and sailboats — someone said there were a hundred, but we're sure it was under sixty — feeding all the more into the pow- ers of imagination. Sitting athwart a parking-lot medi- an, the Maximum Pleasure probably symbolized some- thing now, something ironic, that she hadn't when first named.

Where tongue-clucking ironies were ripe for the picking at the wrecked gambling hall, the Industrial

Canal was more of an "ugh." The surge had raged-past at the twelve-foot mark, tumbling furniture in offices and carrying sections of buildings away. Some of the buildings at Bollinger's Gulf Repair are said to have survived Louisiana storms since between the World

Wars. Now it is thought they'll have to be torn down.

Not only the water, but a generous supply of mud had trailed through -- and while the water could recede or evaporate, the best the mud could do was to lie there and harden. By the time of our inspection on the 22nd, the mud had allgatored into tiles that bordered on attractive, except for the dust they gave off. A Bobcat darted and spun, scraping the mud carpet up into mounds.

How did she get there? Those engineers could explain it, we feel quite sure, but the pushboat Creole

Jane was up on the bulkhead of the Industrial Canal, in sort of a cul-de-sac she should not have fit. She must have arrived from the north, for a set of stout poles would arrest transit to or from points further south. She would have been traveling sideways. Just a few yards off her knees was the solid blank wall of a drydock, with a huge Reinauer barge within. Astern was a build- ing with sheetmetal walls, too close for Creole Jane's liking — as she settled ashore, her fantail rammed through.

A second Reinauer barge sat in a drydock nearby, like the first in for conversion to double-skin, this one at an angle from jostling by Katrina's force. And quite a force it must have been, for evidence elsewhere tells us one thing: when Bollinger sets-up a drydock, it's set-up sturdy.

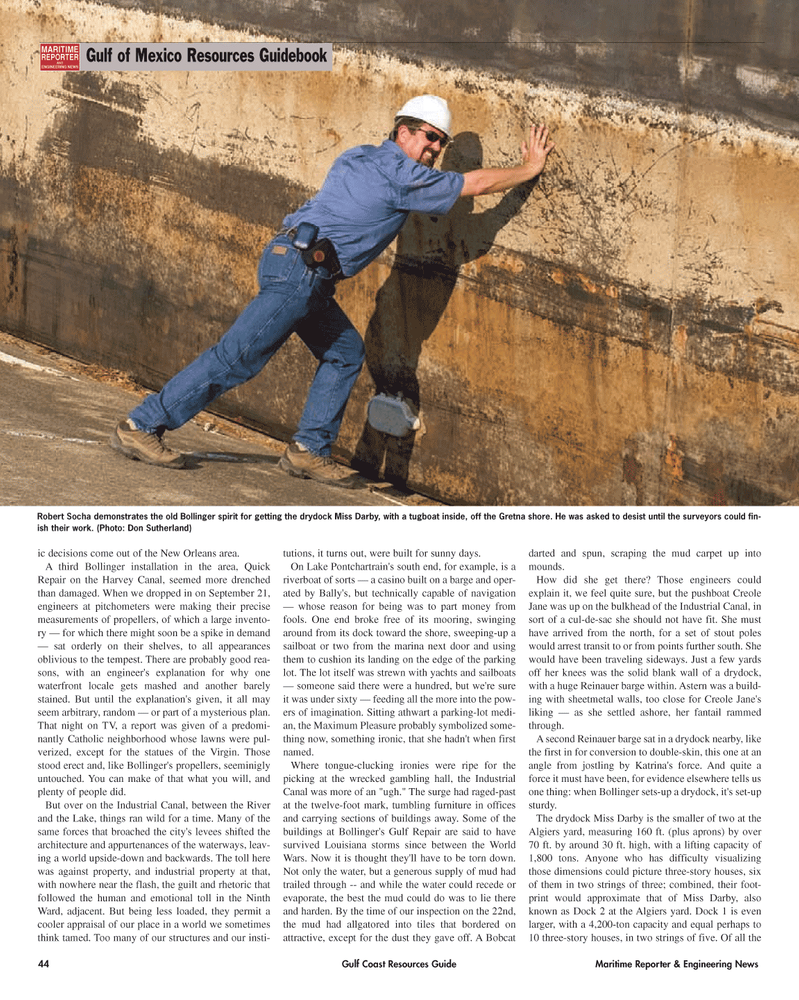

The drydock Miss Darby is the smaller of two at the

Algiers yard, measuring 160 ft. (plus aprons) by over 70 ft. by around 30 ft. high, with a lifting capacity of 1,800 tons. Anyone who has difficulty visualizing those dimensions could picture three-story houses, six of them in two strings of three; combined, their foot- print would approximate that of Miss Darby, also known as Dock 2 at the Algiers yard. Dock 1 is even larger, with a 4,200-ton capacity and equal perhaps to 10 three-story houses, in two strings of five. Of all the 44 Gulf Coast Resources Guide Maritime Reporter & Engineering News

Robert Socha demonstrates the old Bollinger spirit for getting the drydock Miss Darby, with a tugboat inside, off the Gretna shore. He was asked to desist until the surveyors could fin- ish their work. (Photo: Don Sutherland)

MR NOVEMBER 2005 #6 (41-48).qxd 10/28/2005 10:10 AM Page 44

43

43

45

45