Cruise Industry Seeks Fortune in China

Builders, Operators Teaming to Fill Voids In Rapidly Growing Chinese Market

After an uneven couple of years punctuated by struggling economic factors worldwide, maturing markets and some highly publicized accidents and illnesses, the cruise industry is hoping to find a little “double happiness” from the rapidly growing Chinese market – enhanced profits and renewed market growth for both operators and builders.

For its part, the Chinese government is betting on a triple payout: it hopes to serve a growing middle class (estimated at a potential 300 million market) and its desire for cruising vacations, to float its own liners and domestic operators and, to expand opportunities for its financially struggling shipyard industry.

To do this will require, most importantly, ships, the newer the better, and lots of them. The market is currently served by 52 cruise liners of varying capacities and older vintages, with the potential to carry 2.17 million passengers across 1,000 cruises, according to the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA).

To significantly boost that capacity in as timely a manner as possible – cruise ships typically take two to three years to deliver – will require partnerships between the more experienced European cruise shipbuilders and operators and Chinese shipyards and authorities, such as the ones struck separately over the last three months by the world’s largest cruise liner company, Carnival Corp., with the largest cruise ship builder, Fincantieri S.p.A.; with China’s largest shipyard, China State Shipbuilding Corp. (CSSC); and with state agency China Merchant Group, which is focused on transportation, infrastructure, financial services and real estate development. Also in the mix, a recently announced partnership between Royal Caribbean, the second largest cruise line operator, and C-Trip, China’s dominant travel agency with 10% of the market. Even Japan is getting in on the action, with orders for two newbuilds from the AIDA Cruise line arm of Carnival.

The partnerships in China are preliminary agreements aimed at accelerating the development and growth of the cruise industry there, via projects such as building the first domestically sourced cruise ships in China, to building up and out the country’s port and terminal infrastructure, and to creating domestic cruise line operations.

Financial Fireworks

The prize here is stack-blowing market growth and seemingly unlimited opportunity. For starters, the United Nations World Tourism Organization, claims that Chinese tourists became the world’s biggest travel spenders in 2012, paying out a cool $102 billion, and ranked them number one globally in spending in 2013. The Chinese Ministry of Transport (MOT) is committed to developing the Chinese cruise market, and has been projecting that it will become the second largest after the U.S. in a mere couple of years, growing at a faster rate than North America and Europe. MOT also predicts China will reach 4.5 million passengers by 2020, or representing about 50% of global cruisers by some estimates.

The Asian Cruise Association (now a part of CLIA) took a more tempered view of the market last year, estimating that the overall Asian cruise market, which totaled 1.3 million passengers in 2012, could nearly triple to 3.8 million in 2020, including 1.6 million from China.

By any measure or estimate, the Chinese cruise market is on the verge of exploding, a fact not lost on the international players plying the China trade. Also enticing, is the fact that Chinese guests pay more for their typically shorter itineraries.

Since 2013, cruise operators have responded by doubling the number of ships and increasing the number, routes and timing of their cruises. As a result, even in its early stages, that demand has already produced a measureable, and growing, positive impact on the earnings of Carnival and rival Royal Caribbean, so much so that Carnival plans to base a fourth vessel, the 2,978-berth Costa Serena, in China this year, and last year moved its COO in country as a sign of both its commitment and the market’s importance. The company expects to carry 500,000 cruise passengers in China this year. UBS Global Research analysts Robin Farley estimates China will be about 6% of Carnival’s deployments in 2015.

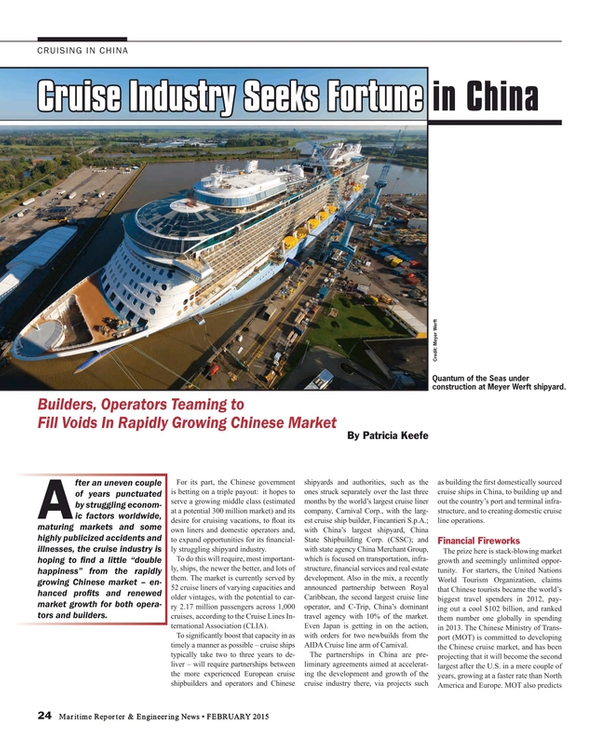

Last April, the Royal Caribbean said its sales in China have doubled over the past five years, though it did not provide specifics. That apparently was sufficient to convince the company to take the unprecedented step of committing its newest vessel, the 4,180 berth Quantum of the Seas, to be based in Shanghai by the spring.

“Royal Caribbean’s decision to base Quantum of the seas full time in Asia is a huge step forward – this is a ship leap-frogging the existing product,” exclaims Ted Blamey, principal of Chart Management Consultants, Australian –based global experts in cruise tourism and strategy, and a producer of market research for industry groups like CLIA and the former Asian Cruise Association. “And Carnival’s decision to move its COO to China speaks volumes about its intention to be a serious player in the Chinese market,” he adds.

A Slow Boat to Market Growth

The government may want to build a vacation market, and the cruise industry may be salivating at the huge untapped potential of the Chinese market, but growth will be stymied by capacity – there simply aren’t enough ships to meet demand. And even if more liners could be redeployed from other more sedate global sectors, it wouldn’t be enough. And it also might not be pleasing to an increasingly sophisticated and status-conscious client base: they don’t want warmed over, outdated ships, which until recently are often what they got. The days of limping old vessels to a once backwater market are over. The situation begs for new builds, but China’s shipyards aren’t up to the task. Cruise ships are very complex and the design, workmanship and variety of activities and number of state rooms aboard a typical cruise ship is far more intricate than the types of vessels being turned out today at most Chinese shipyards.

Even Japan, which has arguably more sophisticated shipbuilding skills, has had a less than glowing experience in the cruise market, dropping in and out over the years.

And yet cruise liners could be a boon to China’s shipyards. While not lacking in orders, they are lacking in profitability and overrun with capacity, so much so that banks have reportedly tightened access to credit to all but China’s biggest shipyards even as other shipyards have been closing, forcing the government to launch a program to reform the sector –creating a so-called “white list” of shipyards eligible for assistance from the state. Cruise liners done right, are both profitable, and in demand. There’s that Double Happiness again.

However, “It will take many years, in my view, before a cruise client will trust a Chinese shipyard to build the entire ship,” says Chart Management’s Blamey.

A situation that again, signals opportunity to Europe’s cruise ship builders, which besides having honed the requisite skills needed to build quality liners, also have the production side down to a science.

“Excluding the AIDA project [now underway] at Mitsubishi, we are down to three companies with four yards – STX France, [Germany’s] Meyer Werft, and then [Italy’s] Fincantieri. They have really gone through a long period of learning what the criteria are needed on the cruise ship end and the logistics involved, to keep those yards viable. It’s a real testament to the experience gained in making the yard efficient in productivity,” says Bud Darr, CLIA’s senior vice president of technical and regulatory affairs.

Ironically, in most sectors of ship building, Asian competitors in China, Korea and Japan loom as a cheaper, often bigger, threat to business. Even though Meyer Werft GmbH and Fincantieri SpA share the bulk - 72% - of the European order book through 2017, including 24 cruise liners with space for 76,161 passengers, contracts placed in Japan and possible orders in China, “represent a threat to Europe’s continued preeminence in cruise shipbuilding,” according to a CLIA Europe June market report.

The probable loss of cruise new builds to Asian shipyards would be a blow to European shipyards, which have already lost other business to their cheaper, typically mammoth and increasingly sophisticated competitors in Korea, Japan and China.

This time though, we may see these shipyards fight back in a manner of speaking, by taking the “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” or at least partner with them, route.

“The Chinese have proven themselves to be very capable at engineering, and capable of learning very fast. But cruise ship building is a very challenging business to get into. Because of the type of specialized ship this is, and the extremely tight deadlines necessary to meet customer demand on delivery, this is not something you get into easily with success. For example, the logistics it takes to keep the product on schedule and on multiple tracks presents a very steep learning curve, and is the type of experience you probably can’t afford to learn on your own. It could prove extremely valuable to Chinese shipyards to partner with others that have had success,” says CLIA’s Darr.

Blamey foresees a situation where at least in the early years Chinese shipyards would build the hulls and handle the assemblies, but partner with experienced cruise ship builders to provide components like state rooms, fittings, some machinery etc.

“The Chinese can lay the hull more cheaply than anyone else, and I think there is a widespread belief that the Chinese will eventually build cruise ships at a high level of quality and at a lower level of cost. So shipyards like Fincantieri might be thinking, Let’s get in on the ground floor, let’s be there first,’ ” says Blamey, referencing Fincantieri’s November MOU with Carnival, in which the Italian cruise ship builder agreed to explore a joint venture to construct ships for the Chinese market.

The MOU could be a model for the typical partnership with Chinese shipyards. While Carnival will provide “the visions, definition and overall specifications” for the ship’s design, Fincantieri would provide its product expertise and other “specialist services” to augment and guide CSSC.

“This agreement . . . testifies our determination in pursuing a strategy that increasingly establishes [us] as a global and reference player in the sector, with a strong presence in all markets that can ensure the future of our business,” said Fincantieri’s CEO, Giuseppe Bono, in a press release.

Survival Strategies

The phrase “reference player” speaks to Blamey’s thoughts on why Fincantieri would want to help an eventual behemoth of a competitor. Building ships by stitching together pre-fabricated sections and parts produced by other partners is common in shipyards today. The strategy cuts costs and speeds production, sure, but in the case of the Chinese cruise market, it is also a way to provide access to the skillsets the Chinese do not yet possess. And if the market takes off as expected, down the road there will likely be plenty of orders for Fincantieri – and its European competitors - with or without working with a Chinese shipyard. In the meantime, Fincantieri can build relationships by sharing its expertise.

It’s not clear what STX or Meyer Werft’s China strategies are, but the German shipyard recently lost two newbuilds to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd., despite having built a seven ships for AIDA between 2007-2013, the largest at 71, 304 tons . The cruise operator’s next two ships, which will weigh in at 125,000 gross tonnage, will be built in Japan, which has a checkered history in cruise builds. But it’s cheaper, significantly so, and as such drew protests from Fincantieri and STX when the deal was announced in 2011.

In any case, one of the reasons for partnering with the Chinese is that they know their market base. Chinese cruise guests have very different expectations and needs, and those will need to be built into new build ship designs or retrofitted onto to older vessels. Here again, the complexities involved in the latter case should provide the European shipyards with yet another money-making opportunity.

According to UBS’ Farley, CLIA’s Darr and consultant Blamey, Chinese differentials include:

• A preference for new, cutting-edge accommodations. The market has been traditionally served by older vessels as Chinese ventures have purchased second-hand ships and western operators have sent aging vessels into the market. Going forward, this won’t do. This is why Quantum of the Seas is expected to give Royal Caribbean a distinct boost in the coming fight for mind space and market share.

• Fewer open decks and more interior spaces devoted to more activities – Westerners typically go on vacation to relax. The Chinese, typically, do not. They are also not sun worshippers, and they like to keep busy. They want to do things and then go back and talk about what they did. The Chinese tend to travel in groups, also, so activities and spaces need to be designed to enable them to stay together.

• Fewer bars and western-style restaurants. The Chinese, say Blamey, don’t like to drink before dinner, eat with strangers or linger over a meal. They drink to be social, eat in a family group and eat quickly, he adds. At least one cruise operator has already ripped out and replaced its dining room in response.

• More space devoted to high-end retail and gambling - the Chinese are big shoppers and gamblers.

• Shorter itineraries – The Chinese have significantly less vacation time than their western counterparts, and so need short trips. This is true even for retirees. Shorter trips, agree Darr and Blamey, means the cruise lines will have to find more people to sell more cruises to, at generally higher ticket prices. More trips means more servicing and more wear and tear over time.

• Last-minute bookings – the Chinese are famous for booking late, and online, which could negatively impact the ability of cruise lines to sell space and estimate capacity and sale as far in advance as they do in the West.

Many Parts Make Up A Whole

Solving the issue of building up the available stock of cruise liners, and making sure they meet the unique needs of Chinese vacationers, is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to building out the Chinese cruise market. There are other challenges to be addressed as well. Those ships need places to go. They need to be able to dock, and they have to be serviced in an efficient manner. Passengers need access to terminals and all manner of transport to get to and from their cruises.

“Without infrastructure, you can’t operate in a substantial way,” notes Darr.

This creates opportunity for cruise line operators, which can further influence the market and build mind share and contacts by also teaching domestic cruise partners the business of cruising, and by helping local and state governments to plan and flesh out the other pieces of the cruising picture – ports, sizeable terminals, efficient movement of passengers and supplies on and off cruise ships, destination activities and other events.

One thing the Chinese are very good at, according to Blamey, is designing and building high-quality infrastructure, and getting it done quickly. It has already begun to modernize some key ports, building out berths capable of supporting cruise ships. “Both Singapore and Hong Kong have recently expanded their cruise ports and many coastal cities in China have developed port infrastructure in the last eight years,” observes UBS’ Farley. Overall, China has five cruise terminals in operation, but more work needs to be done. So far, it reportedly has three more under construction and another five or so in the planning stages.

Reading the Tea Leaves

What will happen once the Chinese skillset catches up with the West, and when that might be, is anyone’s guess, but it behoove European cruise liner builders to get in the game now, to build the relationships necessary for when the elephant in the shipyard is able to stand on its own. In the meantime, there is money to be made in helping the Chinese build their own cruise ships, the possibility of setting up lucrative joint ventures within China going forward, and the potential for enough demand to feed East and West shipyards.

“As potential goes, you have to look at China with a very optimistic eye. Whether or not our industry can succeed in business only time will tell, but you can see the investment in time and resources that will be necessary to bring that to fruition,” says CLIA’s Darr.

One thing is for sure, the leaders in cruise industry ownership, operation and ship builders have read the tea leaves, and are leading the way for the rest of the industry to work out a peace with their Chinese competitors that, if they play their cards right, will eventually lead to a win for everyone in this game – ship builders, tourists, cruise operators, local attractions, the Chinese government, etc. – and launch a lucrative, golden age of Chinese cruising.

Read Cruise Industry Seeks Fortune in China in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of February 2015 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from February 2015 issue

Content

- Editorial: Gettin’ Crabby with Deadliest Catch page: 6

- Zeroing in on Zukunft page: 8

- Deadliest Catch: The Quest to Coat Cornelia Marie page: 10

- Seafarers ... Get Some Rest! page: 14

- Floating Wind Power: A Semisubmersible Floating Turbine Foundation page: 14

- Floater Orders 2014 page: 16

- New Study to Provide Insight into Passenger Ship Comfort page: 20

- Ship Salvage in the Presence of WWII Era Torpedo & Mines page: 22

- Cruise Industry Seeks Fortune in China page: 24

- Efficient Computer Control with G&D page: 32

- RCCL Plans to Scrub Emissions into Shape page: 34

- BIG DATA & Big Savings for Maritime Ops page: 34

- USS America: LHA with an Aviation Focus page: 36

- Austal Delivers for Militaries ... Near & Far page: 38

- Broadband Bandwidth Battles page: 42

- Finland: A Maritime Powerhouse page: 46

- Denmark's Promising Future page: 48

- Virtual Aids to Navigation Mark Research Equipment page: 54

- First ShipArrestor Delivered page: 55