The aging Pacific Northwest fishing fleet is either undergoing or about to undergo a long-overdo upgrade, judging by a major economic report commissioned by the Port of Seattle. Fisheries managers, seafood suppliers, yards and the supply chain all hope an accompanying surge in ship finance “lifts all boats”. For now, the newbuild count is growing apace, slowed just a bit by owners opting for major retrofits amid rich fish harvests. This fisheries upsurge comes with some rising stars of ship design-and-build for vessels set to ply the Bering and Beaufort seas.

The '70s were the heyday of boatbuilding — half of the current U.S. Pacific Northwest’s 400-strong fleet of vessels over 58 feet were built when sideburns were mandatory. The fleet’s boats are so well-maintained, most of them, that they’re still candidates for retrofits of engines, holds, electrical systems and deck machinery.

Modernization of the North Pacific Fishing Fleet, a study by The McDowell Group for the Port of Seattle, has made the rounds and given weight to the idea that a major fleet upgrade really is underway. With average 2014 gross revenues having run between $2 million for Bering Sea/Aleutian Island trawl vessels to $16 million for some catcher-processors, there’s a feeling that owners can afford new vessels that might cost $15 million for the first group or $130 million for the second. Despite the big harvests, just one large vessel a year has been built or heavily modified since 2000. That’s about to change.

The study showed that vessels over 30 years of age are worth about $9 billion in “replacement value” to the supply chain. Those built when the Vietnam War ended, or before, represent $4.4 billion if replaced. “The results of this analysis (of average vessel age) indicate $1.6 billion (or 37 new vessels) in modernization projects will be completed within the next 10 years, assuming no significant changes in financing options. In some cases, vessels will be retired without replacement, and in others two or more vessels will be replaced with a single larger or more efficient vessel,” McDowell researchers credibly assert. Increasingly, too, many of the upswing’s vessels will be of efficient U.S. design. “The European designs seem to have the owners’ attention, but there are several U.S. engineering firms that have (comparable) designs,” Stephen J. Berthold, Eastern Shipbuilding’s VP of sales, tells us in an email.

He goes on to name five U.S. designers which can compete with European designs, although Eastern appears to be “aggressively perusing new 2017 and 2018” work of all types.

Risk Abated

The McDowell compilations suggests that to pick up the pace, “one-off” builds might need to yield to other build models.

Some European designers spread the risk of a build between themselves and a consortium of partners, with the chosen yard asked to just build more runs of a single hull type to earn some economies of scale. In the U.S., some lender risk has been removed by federal building credits, and some owner risk has been dumped in recent rules changes that grant owner the right to upgrade or build a new vessel for previously protected species. Finally, the chasing away of other nations’ vessels from U.S. economic zones has changed out risk with near-certain reward. Now, savings and quotas can be used as equity and collateral toward newbuilds.

Authorities in seafood and building hub now know that an average of three new or totally altered vessels are due out each year between 2017 and 2021. By 2022, and possibly into the future, five large boat projects a year are forecast. These builds would top an upswing which, in the past four years, has seen 13 vessels built. The surge continues from 2016 to 2021, as 15 are projected built. Twenty-two more are due between 2022 to 2026. The Report suggests half of these will be new-builds built in Puget Sound, Washington, although count on “Florida” coming through, too.

International Designs

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the fisheries revival — delayed by the earlier boom-bust, grab-and-go fishery — has already seen established features of modern European designs get their U.S. Northwest debut.

The seiner style pump that sucks rather than dumps a catch onboard will help more catch meet the standards of demanding buyers. The new cod long-liner freezer vessel, Blue North, a $36 million Skipsteknisk ST-155L build, will see crews work in the safety of a moonpool rather than risking being washed overboard or hooked. The Alaskan pollock ground-fish fleet will see new trawlers, including three other designs from the drawing boards of Skipsteknisk in Norway. In Panama City, Florida, two are being built: a 59.1 meter x 14.9m ST-115 trawler for O’Hara Corp. and an ST-118 that’s 80m x 17m for an unnamed U.S. customer.

Skipsteknisk sales manager for fishing boats, Inge Bertil Straume, points us to the 79.8 x 15.4 m ST-116XL being built for Fishermen’s Finest at Dakota Creek Industries in Anacortes, Washington. This boat — built to carry 49 crew with their own hospital — is a replacement built to catch and freeze at sea a series of whitefish products, including cod plus yellow and black sole in the Gulf of Alaska, Chukchi Sea and Bering Sea. A MAN diesel engine will give this first ST-116XL to operate in the U.S. a top speed of 15 knots. The Blue North, too, will have plant to produce fillets, cod liver and the cosmetics ingredient, collagen, a Pacific Northwest nod to the added value in upping fish use by 30 percent to 90 percent. The moonpool joins the “heavily weighted” box keel design and anti-roll tank for low weight and stability as U.S. firsts. The Blue North’s diesel-electric, dual-azimuth propulsion will also meet Tier III environmental strictures for U.S. waters.

Conversion Captivates

At Jensen Marine, management and designers working with operators of long-liners, trawlers, catcher boats and large factory trawlers say they’re feeling the revival.

“This year we have found that the cod fisheries have been very active with new long-liners, and the pollock industry is looking at new factory trawlers and catcher boats,” writes Jensen Maritime VP, Mark Miller, during a pause. To stay with the trend, “We have developed new designs in all these areas that address efficient vessels to operate and process fish.” The 55-year-old Seattle yard has been a commercial “go-to” naval architecture and engineering firm for years with many of the larger operators off the Pacific and Alaskan coasts hiring the firm. Miller says about 30 percent of the business is conversions “at the moment”, although, “The buzz is such that we think that percentage will increase in 2017. We are currently working on a long-liner conversion at a shipyard and have done drawings for our clients of conversions of OSV’s to fishing vessels.” Seafood company Global Seas had its Defender fishing boat re-engineered by Jensen Maritime. The Defender was converted from East Coast (herring and mackerel) to West Coast (pollock) at Patti Marine Enterprise, Florida. It, too, got a fish pump.

“We’re designing more efficient hulls to decrease drag, (and) diesel electric is another feature which makes sense for some of the fisheries,” Miller says. He confirms an increased interest in specific retrofits: “Increasing the factory processing space allows the operator to process more efficiently (with new plant), add new products to their line and in certain cases provide a higher quality product.”

Specific Retrofits

Seattle’s Glacier Fish Company is making the most of its existing fleet by retrofit, redesign and good maintenance. In 2013, this maker of frozen-at-sea Bering Sea cod and pollock had Vigor shipyard of Seattle refit the Alaska Ocean in a job that still resonates as an ideal investment to the serious observer.

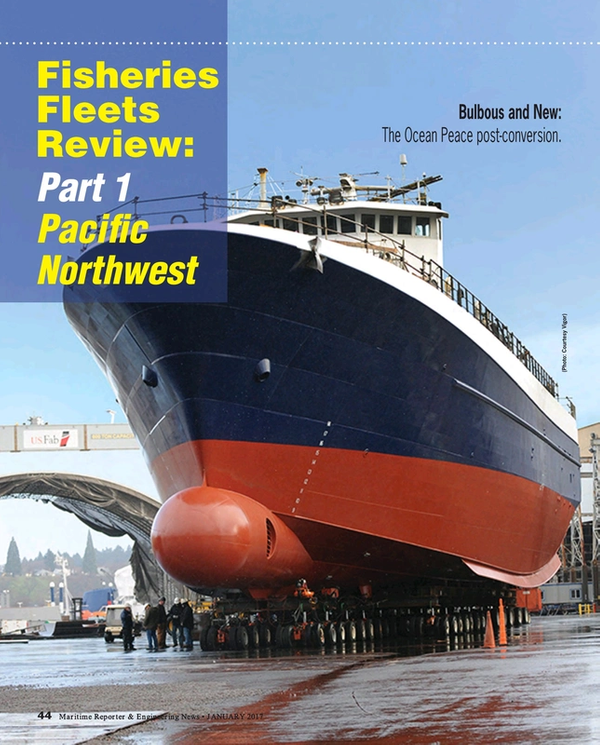

Vigor teams replaced an old fish meal plant with a modern one by cutting a hole in the hull and widening the hold before installing an integrated propeller and rudder made for retrofits. Another vessel, the Ocean Peace, was retrofitted for Ocean Peace Inc. with a bulbous bow, a bow thruster and emergency power in just four months. These conversions — with their time to increased earnings — compete hard with newbuilds in the minds of owners. O’Hara’s conversion of the Araho at Eastern Shipbuilding garners attention, too. The 194-foot Araho was a 90’s era scallop boat from the East Coast, but now O’Hara says, “It will be the most technologically advanced fishing boat in the Bering Sea.”

Who Can, Can’t

In general, smaller fleets and vessels are expected to see less of the revival. “The catcher vessel sector has experienced less recapitalization likely due to (an) inability to add value through onboard processing,” McDowell researchers say, adding, “… It is anticipated that vessels with large amounts of (catch) quota are most likely to be upgraded … Most of the recent upgrades include factory upgrades, such as a fish oil plant.”

On the finance side, the renewal is expected to continue for a couple of reasons: the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Fisheries Finance Program yielded in 2014 to allow more new vessel construction and not just vessel replacement. Finance for 80 percent of vessel cost and a maximum term of 25 years was extended to builds that cost up to $100 million (previously $59 million).

Alaska, needless to say, has gotten word of this.aAnd now Washington and Oregon know, too.