Page 16: of Marine News Magazine (September 2012)

Environment: Stewardship & Compliance

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of September 2012 Marine News Magazine

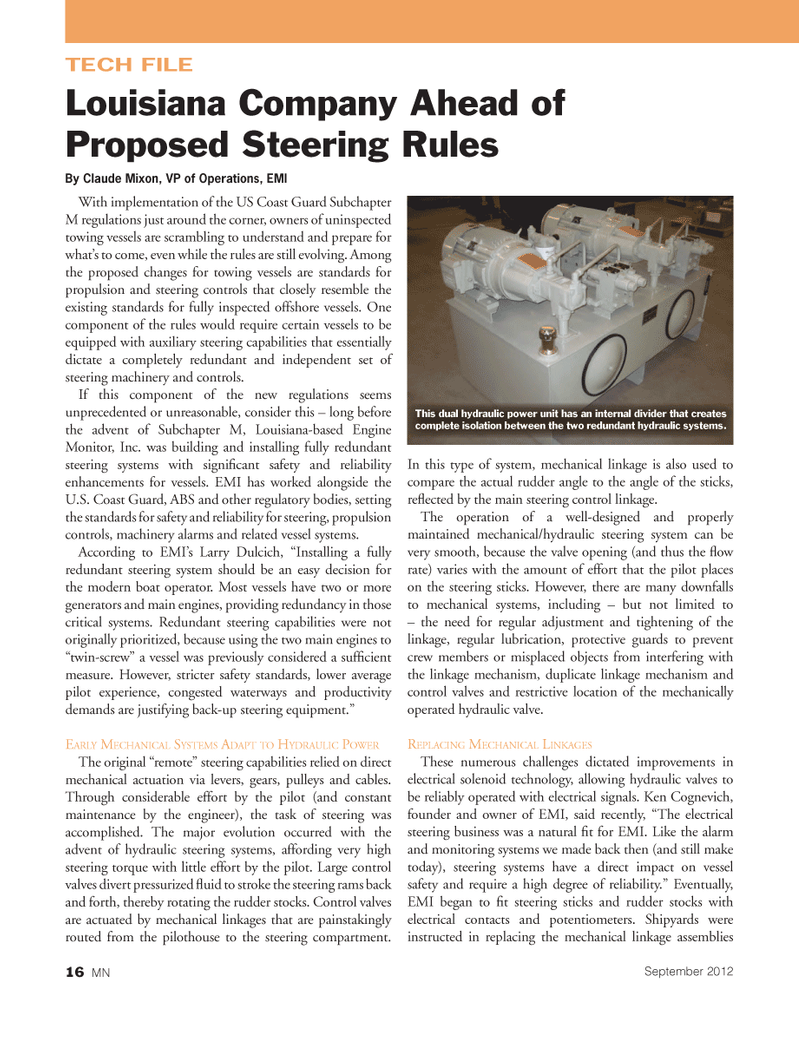

With implementation of the US Coast Guard Subchapter M regulations just around the corner, owners of uninspected towing vessels are scrambling to understand and prepare for what?s to come, even while the rules are still evolving. Among the proposed changes for towing vessels are standards for propulsion and steering controls that closely resemble the existing standards for fully inspected offshore vessels. One component of the rules would require certain vessels to be equipped with auxiliary steering capabilities that essentially dictate a completely redundant and independent set of steering machinery and controls. If this component of the new regulations seems unprecedented or unreasonable, consider this ? long before the advent of Subchapter M, Louisiana-based Engine Monitor, Inc. was building and installing fully redundant steering systems with signi cant safety and reliability enhancements for vessels. EMI has worked alongside the U.S. Coast Guard, ABS and other regulatory bodies, setting the standards for safety and reliability for steering, propulsion controls, machinery alarms and related vessel systems. According to EMI?s Larry Dulcich, ?Installing a fully redundant steering system should be an easy decision for the modern boat operator. Most vessels have two or more generators and main engines, providing redundancy in those critical systems. Redundant steering capabilities were not originally prioritized, because using the two main engines to ?twin-screw? a vessel was previously considered a suf cient measure. However, stricter safety standards, lower average pilot experience, congested waterways and productivity demands are justifying back-up steering equipment.? EARLY MECHANICAL SYSTEMS ADAPT TO HYDRAULIC POWER The original ?remote? steering capabilities relied on direct mechanical actuation via levers, gears, pulleys and cables. Through considerable effort by the pilot (and constant maintenance by the engineer), the task of steering was accomplished. The major evolution occurred with the advent of hydraulic steering systems, affording very high steering torque with little effort by the pilot. Large control valves divert pressurized uid to stroke the steering rams back and forth, thereby rotating the rudder stocks. Control valves are actuated by mechanical linkages that are painstakingly routed from the pilothouse to the steering compartment. In this type of system, mechanical linkage is also used to compare the actual rudder angle to the angle of the sticks, re ected by the main steering control linkage. The operation of a well-designed and properly maintained mechanical/hydraulic steering system can be very smooth, because the valve opening (and thus the ow rate) varies with the amount of effort that the pilot places on the steering sticks. However, there are many downfalls to mechanical systems, including ? but not limited to ? the need for regular adjustment and tightening of the linkage, regular lubrication, protective guards to prevent crew members or misplaced objects from interfering with the linkage mechanism, duplicate linkage mechanism and control valves and restrictive location of the mechanically operated hydraulic valve. REPLACING MECHANICAL LINKAGES These numerous challenges dictated improvements in electrical solenoid technology, allowing hydraulic valves to be reliably operated with electrical signals. Ken Cognevich, founder and owner of EMI, said recently, ?The electrical steering business was a natural t for EMI. Like the alarm and monitoring systems we made back then (and still make today), steering systems have a direct impact on vessel safety and require a high degree of reliability.? Eventually, EMI began to t steering sticks and rudder stocks with electrical contacts and potentiometers. Shipyards were instructed in replacing the mechanical linkage assemblies TECH FILELouisiana Company Ahead of Proposed Steering Rules By Claude Mixon, VP of Operations, EMIThis dual hydraulic power unit has an internal divider that creates complete isolation between the two redundant hydraulic systems. 16 MNSeptember 2012MNSept2012 Layout 1-17.indd 16MNSept2012 Layout 1-17.indd 168/30/2012 2:47:16 PM8/30/2012 2:47:16 PM

15

15

17

17