Page 10: of Marine News Magazine (November 2012)

Workboat Annual

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of November 2012 Marine News Magazine

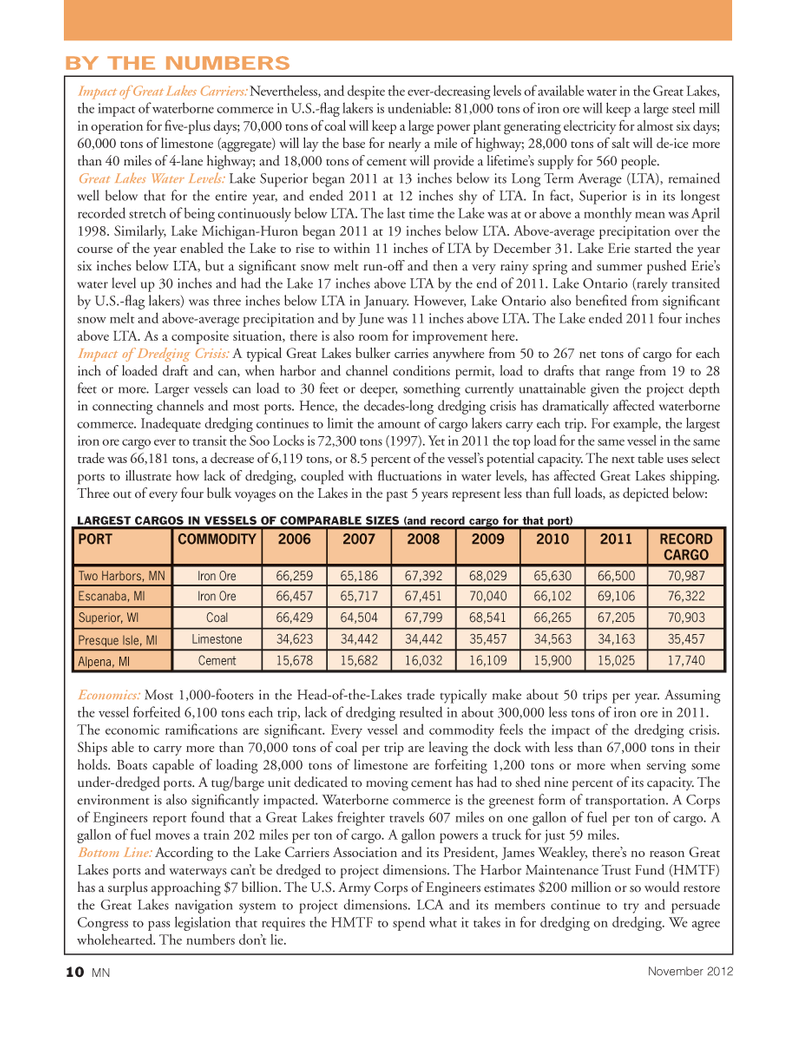

Impact of Great Lakes Carriers: Nevertheless, and despite the ever-decreasing levels of available water in the Great Lakes, the impact of waterborne commerce in U.S.-ß ag lakers is undeniable: 81,000 tons of iron ore will keep a large steel mill in operation for Þ ve-plus days; 70,000 tons of coal will keep a large power plant generating electricity for almost six days; 60,000 tons of limestone (aggregate) will lay the base for nearly a mile of highway; 28,000 tons of salt will de-ice more than 40 miles of 4-lane highway; and 18,000 tons of cement will provide a lifetimeÕs supply for 560 people. Great Lakes Water Levels: Lake Superior began 2011 at 13 inches below its Long Term Average (LTA), remained well below that for the entire year, and ended 2011 at 12 inches shy of LTA. In fact, Superior is in its longest recorded stretch of being continuously below LTA. The last time the Lake was at or above a monthly mean was April 1998. Similarly, Lake Michigan-Huron began 2011 at 19 inches below LTA. Above-average precipitation over the course of the year enabled the Lake to rise to within 11 inches of LTA by December 31. Lake Erie started the year six inches below LTA, but a signiÞ cant snow melt run-off and then a very rainy spring and summer pushed ErieÕs water level up 30 inches and had the Lake 17 inches above LTA by the end of 2011. Lake Ontario (rarely transited by U.S.-ß ag lakers) was three inches below LTA in January. However, Lake Ontario also beneÞ ted from signiÞ cant snow melt and above-average precipitation and by June was 11 inches above LTA. The Lake ended 2011 four inches above LTA. As a composite situation, there is also room for improvement here. Impact of Dredging Crisis: A typical Great Lakes bulker carries anywhere from 50 to 267 net tons of cargo for each inch of loaded draft and can, when harbor and channel conditions permit, load to drafts that range from 19 to 28 feet or more. Larger vessels can load to 30 feet or deeper, something currently unattainable given the project depth in connecting channels and most ports. Hence, the decades-long dredging crisis has dramatically affected waterborne commerce. Inadequate dredging continues to limit the amount of cargo lakers carry each trip. For example, the largest iron ore cargo ever to transit the Soo Locks is 72,300 tons (1997). Yet in 2011 the top load for the same vessel in the same trade was 66,181 tons, a decrease of 6,119 tons, or 8.5 percent of the vesselÕs potential capacity. The next table uses select ports to illustrate how lack of dredging, coupled with ß uctuations in water levels, has affected Great Lakes shipping. Three out of every four bulk voyages on the Lakes in the past 5 years represent less than full loads, as depicted below: LARGEST CARGOS IN VESSELS OF COMPARABLE SIZES (and record cargo for that port) Economics: Most 1,000-footers in the Head-of-the-Lakes trade typically make about 50 trips per year. Assuming the vessel forfeited 6,100 tons each trip, lack of dredging resulted in about 300,000 less tons of iron ore in 2011. The economic ramiÞ cations are signiÞ cant. Every vessel and commodity feels the impact of the dredging crisis. Ships able to carry more than 70,000 tons of coal per trip are leaving the dock with less than 67,000 tons in their holds. Boats capable of loading 28,000 tons of limestone are forfeiting 1,200 tons or more when serving some under-dredged ports. A tug/barge unit dedicated to moving cement has had to shed nine percent of its capacity. The environment is also signiÞ cantly impacted. Waterborne commerce is the greenest form of transportation. A Corps of Engineers report found that a Great Lakes freighter travels 607 miles on one gallon of fuel per ton of cargo. A gallon of fuel moves a train 202 miles per ton of cargo. A gallon powers a truck for just 59 miles. Bottom Line: According to the Lake Carriers Association and its President, James Weakley, thereÕs no reason Great Lakes ports and waterways canÕt be dredged to project dimensions. The Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) has a surplus approaching $7 billion. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates $200 million or so would restore the Great Lakes navigation system to project dimensions. LCA and its members continue to try and persuade Congress to pass legislation that requires the HMTF to spend what it takes in for dredging on dredging. We agree wholehearted. The numbers donÕt lie. BY THE NUMBERSPORT COMMODITY 200620072008200920102011RECORD CARGOTwo Harbors, MN Iron Ore 66,25965,18667,39268,02965,63066,50070,987 Escanaba, MI Iron Ore 66,45765,71767,45170,04066,10269,10676,322 Superior, WI Coal 66,429 64,50467,79968,54166,26567,20570,903 Presque Isle, MI Limestone 34,623 34,44234,44235,45734,56334,16335,457 Alpena, MI Cement 15,678 15,68216,03216,10915,90015,02517,740 10 MNNovember 2012MNNov2012 Layout 1-17.indd 10MNNov2012 Layout 1-17.indd 1011/6/2012 4:14:02 PM11/6/2012 4:14:02 PM

9

9

11

11