Page 26: of Marine News Magazine (July 2022)

Propulsion Technology

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of July 2022 Marine News Magazine

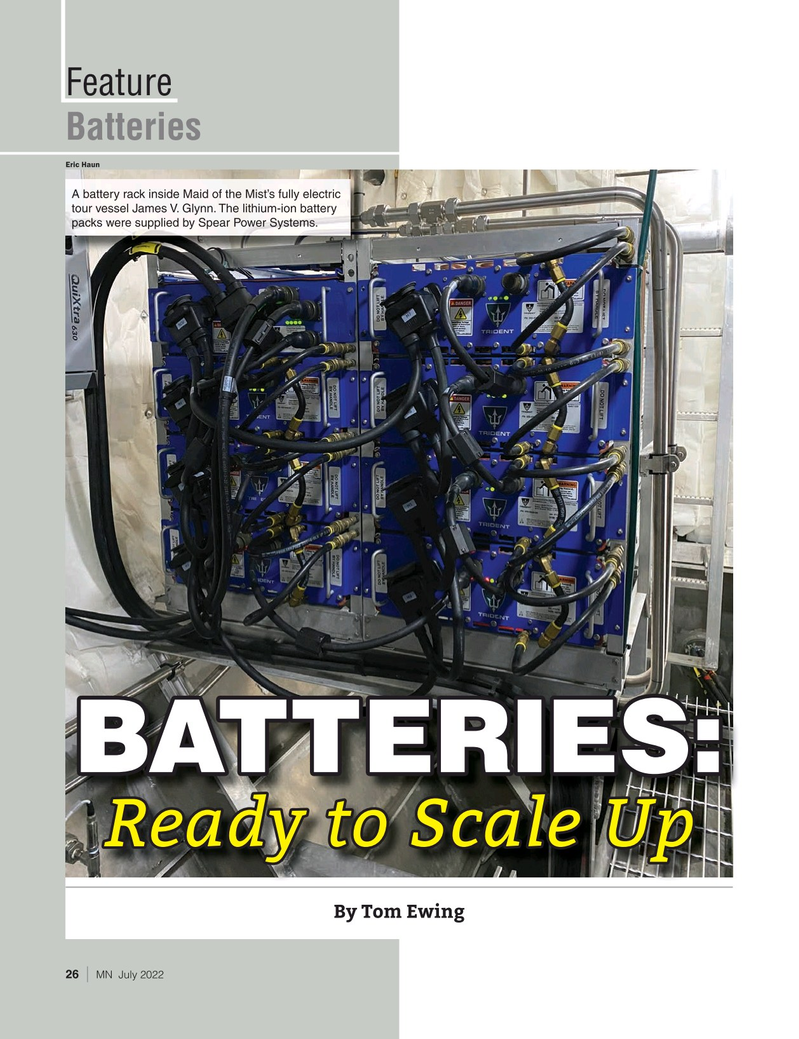

Feature

Batteries atteries for maritime power picked up big momen-

US trends tum in May, bene? ting from the most basic con-

Ben Wrightsman is President and CEO of the Battery cept within Econ 101: supply and demand.

B

Innovation Center (BIC), based in Crane, Ind. The BIC

On May 19 Corvus Energy announced it would estab- works for the development, testing, commercialization lish a lithium ion battery manufacturing facility in Port and advanced learning of high-performance and light-

Bellingham, Wash., just north of Seattle. Corvus Energy is weight energy storage systems for commercial, defense and a leading supplier of battery energy storage systems (BESS) industry partners. BIC works closely with the Navy’s high- for marine applications. Its systems already power more energy focused Naval Surface Warfare Center, also located than 30 North American vessels, as well as 29 hybrid port in Crane. BIC signed on as a DOE “team member” for cranes and 11 land-based drilling rigs.

DOE’s battery innovation initiative, announced in May,

Geir Bjørkeli, Corvus CEO, said the company has “seen the Agency’s $7 billion, ? ve-year effort, focusing on bat- a signi? cant uptake in orders from the U.S. market as well tery materials processing and manufacturing.

as a growing commitment from the government and in-

In an interview Wrightsman commented that maritime dustry players on reducing GHG emissions. Increased ca- battery applications, indeed, have reached an off-the-shelf pacity and production ? exibility will be key to meeting status, but he still characterized the U.S. market as “pilot anticipated growth.” scale”, at least compared to European and Asian markets.

The new facility will have an annual capacity of 200

Wrightsman said that the battery supply chain presents

MWh of stored energy capacity. Individual vessels typi- challenges. Lithium costs have increased, and future de- cally have a capacity between 0.5 and 10 MWh installed, mand will add pricing pressures. Raw materials are avail- explained Sveinung Ødegard, Americas president at Cor- able today, but he expects supply risks by 2030. “If you vus Energy. Corvus’ goal is to start delivery from a new don’t change anything,” he noted, with particular reference factory in Q4 this year.

to the U.S. regulatory process, “we run risks of shortages.

In its announcement Corvus cited increased demand We need domestic production.” from the tug industry.

Regarding safety, Wrightsman believes today’s batteries

Also on May 19, Houston-based Industrial Service Solu- are “inherently safe” and that safety advances will continue, tions (ISS) announced it is seeking bids from U.S. shipyards although at a cost. However, he said that overall declining to build up to four hulls for what will become North Amer- costs will offset safety related increases. For comparison, ica’s ? rst fully-electric towboats. The zero-emissions vessels, he noted that fossil fuel systems, after 100 years, present which will be constructed for New York-based Zeeboat and numerous safety risks, from handling to storage to ? nal available for charter from 2025, will run entirely on battery combustion. Still, these risks are considered acceptable to- power, without the use of diesel engines—a ? rst for towboats day. He expects a similar safety pathway for batteries.

in North America. The batteries for this project are already sourced—from Shift Clean Energy, based in Vancouver, B.C.

The future: How fast is it approaching?

These announcements continue to con? rm that maritime

Batteries are expensive, heavy and can present extreme battery applications are moving out of the experimental hazards—and they need to be recharged. Batteries—really stage, that vessel electri? cation is available and in demand.

electric storage systems (ESS)—require extensive shoreside [For a demonstration, including discussion, of a large infrastructure. And if batteries are to be part of a green scale maritime ESS project check out the video of a bat- energy transition (why else make such a move?) that shore- tery-powered ferry making a 4-kilometer crossing, 46 side infrastructure needs to be connected to constant, un- times per day, every 15 minutes, between Helsingborg, varying and on-demand supplies of renewable electricity,

Sweden and Helsingør, Denmark. The ferry pauses to including utility scale storage; in effect, batteries charging charge on each side. It transports over 7 million passengers batteries. Even for niche operations in a harbor, it can’t be and nearly 2 million vehicles annually—clearly a battery questioned when a vessel—not to mention 100 vessels— powered workhorse. Of particular interest, note the giant need maximum power, simultaneously.

shoreside charging device.] “State of charge” (SoC) is an important concept in bat- www.marinelink.com MN 27|

25

25

27

27