Carlo Zaffanella is vice president and general manager of Maritime and Strategic Systems (M&SS) for General Dynamics Mission Systems. The M&SS business includes submarine and surface ship electronic systems integration as well as the design, build and support of a broad array of subsurface, surface, air, airport and strategic subsystems, meaning he is perfectly positioned to lead MTR’s ‘vehicles’ edition, as in 2018 our attention turns from a specific products and systems, to the holistic web of connectivity between subsea, surface, land-, air- and space-based assets.

Please give a description of the business unit you lead and your responsibilities.

I run the Maritime and Strategic Systems (M&SS) line of business for General Dynamics Mission Systems, part of General Dynamics Corporation. M&SS is a pretty broad, large, and steeped in the traditional maritime business that has been on a strong and sustainable growth curve for 20 plus years. Basically we do electronics – especially mission systems – system integration, and product development for many maritime programs. And then the word “strategic” that’s in that acronym, as well, “strategic” meaning “nuclear” so think Navy nuclear. I have four businesses – Navy Air, Navy Surface, Navy Undersea, and Strategic. In total we are about 3,000 people in about two dozen locations across the country.

OK, let’s start broad. Looking at the world of UUVs, AUVs, unmanned systems, by broad geographic region or market, where do you see opportunities in the years ahead and why?

Let’s rewind roughly 20 years, back to the mid-late 1990s, and think about UAVs. If you would have asked about UAV business (and looking ahead), would they have told you:

- “We see a private company delivering packages to your doorstep using drones.”

- “We see power line and wind turbine inspection, aerial construction.”

- “We see window cleaning in Dubai.”

It is unimaginable what has happened in the last 20 years to UAVs. Why did that happen? Because they became really useful as the technologies fell in line, making it possible to do things that we simply could not imagine back then. So I’m going to caveat my answer to tell you that I think that’s where we are with UUVs – technologies are falling in place. And the answer I give you today will probably seem horrifyingly myopic 10 to 20 years from now and probably unimaginative. But having said all that, what do we see in near-term?

UUVs give us access and give us data that manned systems simply can’t. We keep people out of harm’s way, we get into niches and places that manned systems can’t get to. So anywhere you see an application – whether it’s keeping a sailor safe, or keeping a diver safe, inspecting infrastructure, inspecting vehicles – things that are tedious, those tend to be great things for unmanned systems. One obvious area is mine warfare. It is a nasty business, and in addition to keeping sailors safe, it also can do a lot more. You have a stand-off distance that is tremendous, and you can do things persistently that would have been very hard to do with a man in the loop. We’ve taken some major strides in maturing the technologies so that now it’s gone from pretty good theory to real practice.

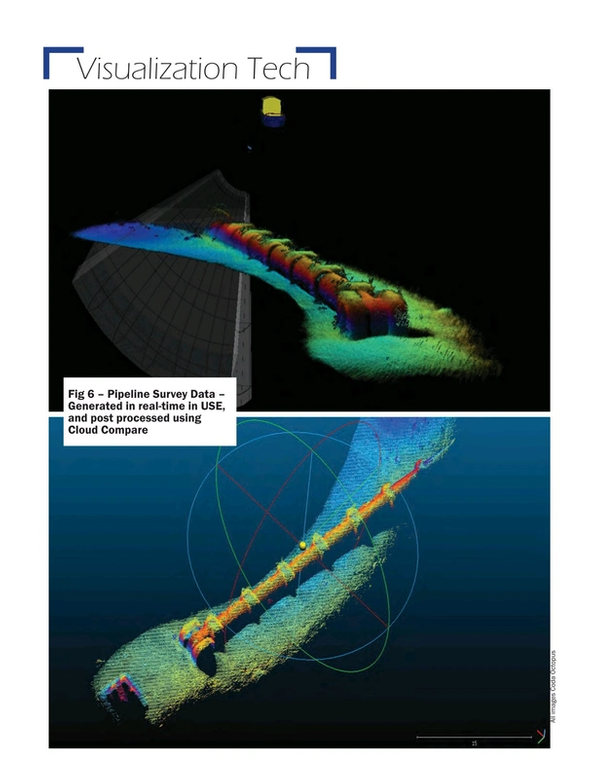

From oceanography to inspections under the Polar ice cap, to pipeline monitoring, to ship hull inspection and searching for lost vessels, unique applications continue to emerge. Simply put, the technology is just getting better – and it’s getting better quick. Twenty years down the road my answer today will feel incredibly short-sighted. At least that’s my hope.

Looking at the last five years, what do you see is the most significant technology advance that has really helped to take the tech to the next level?

That’s an interesting question. So I’m going to give you the “GD answer” in the sense of what has mattered to us, as opposed to the world of UUVs. We are largely a defense company, although our interest from a UUV standpoint is defense and commercial. There is no question that the most important things that we have been doing is to turn theoretic, fairly scientific and “research-y” vehicles into reliable, usable, predictable, GD-quality products that the Navy can buy and rely on to do their job. I know that doesn’t sound “sexy” and perhaps you look for answers like autonomy, power, and distance communications, for example. All of those are important, but underpinning them is that these things can’t be toys – they can’t be things that are disposable or unreliable.

They need to be serious instruments and that’s what we are developing. It doesn’t do you any good to have spectacular autonomy, great power and tremendous power densities if every four hours you have to take your vehicle out of the water and repair it. And frankly, that’s where a lot of UUVs were for the military recently. I think we’re breaking that barrier.

So obviously there have been a lot of great strides both on and under the water in autonomy. But it could be argued that maritime has trailed the trajectory of land- and air-based systems. Do you agree or disagree with that statement, and why?

Certainly it has trailed, but I think that the same ingredients (that drove UAVs 20 years ago) are now falling into place. Power density is coming way up, as it is a limiting factor for UUVs, just like it is for UAVs.

We’ve put in excellent resources toward making the kind of batteries that are modular, replaceable, high density, usable, transportable – and that has helped us immensely. Autonomy is complicated under the water in the sense that you can’t communicate the same way, so when a system goes out there (underwater), its ability to sense is more limited, taking you to the need to signal process at very advanced levels.

Well, good news! Signal processing technology is progressing rapidly, and a company like GD that makes signal processors for all sorts of applications. We are able to, in a much smaller package, do much more onboard processing. That means that not only can we help the vehicle itself with autonomy, vehicle management and energy management – but the payload, too, whatever that payload might be. As a result we’re seeing a substantial increase in real money being put towards buying these products to use them in real systems, especially on the military side. I think signal processing is a big part of that.

And then there is reliability. As I mentioned, the Navy makes assumptions that when you deliver a system like this, it’s going to work exactly as advertised delivering the kind of reliability that they need. And I think if you look at our products, you’re seeing that tremendous change is really high-end reliability, and that’s going to make those other technologies much more useful.

While your responsibility and experience transcends underwater systems, when you look at the biggest challenge to delivering an effective, cost-efficient product or system for operation in the world waterways, what do you consider to be the number one challenge today?

Let’s say you solved the problem of making your UUV reliable; it’s developed, it’s trusted, it’s autonomous. So now what is it doing? If it is collecting a tremendous amount of data but shipping it back with a low bandwidth of undersea comms, that’s a challenge. If it just sits there and stores data and gives it to you later when it comes home, that’s a different challenge and it is hardly real-time.

As we push the frontier of reliability, as we push the frontier of autonomy, as we push the frontier of power, and so now you get to Nirvana, right? Your UUVs can be out there for a super long time, but what are they doing if they can’t give you back the information that matters?

Our job is to solve missions, so we have a much broader view of what it takes to make a UUV useful – from launch and recovery, to cyber security, to data management, to the data fabric that allows the communication under and above the water – these are all parts of the problem. And I think that the UUV community, largely, is focused on solving the “put a vehicle under the water and make it autonomous” problem. That’s just a piece of the puzzle – we want to solve the puzzle.

Looking at the vehicles, can you give us an overview of the ‘fleet’ under your guidance?

You can’t make an infinite array of products; it’s just not a reasonable way to run a business. So what we’ve done is we’ve been working with engineering and business development to understand the market need. We focused on a family, starting with the smallest offering which is Sand Shark – low cost, single person portable, leveraging miniaturized sensors. Then we have “intermediate diameters” and we’re productizing those now. They existed already in the Bluefin suite, but we’ve taken a hard look from the ground up, re-engineering them to make them modular and cost-friendly, a repeatable, producible device.

Then there’s the 21-inch diameter which is the basis for Knifefish.

If you had to pick one of the products in the family and tell me what you think has the best near-term potential, which one and why?

I would say it’s the 21, as it has been the beneficiary both of the Navy’s investment and our own. It has a lot of payload flexibility. It is capable of being launched and recovered from existing Navy assets, and it is also capable of launching its own UUVs. I see it as a building block not just for us, but for the Navy, and in doing that, as we standardize on that product, we drive its price down and its commercial viability goes up. This is a 4500 meter vehicle that takes you to the vast majority of the ocean’s waters. And you can do a whole lot with that, both commercially, scientifically and militarily.

(NOTE: Late last year a specialist team from General Dynamics Mission Systems demonstrated the unique capabilities of the Knifefish, a medium-class mine countermeasure (MCM) unmanned undersea vehicle (UUV), during contractor trials for the U.S. Navy. The tactical UUV is designed using an open architecture concept that can be quickly and efficiently modified to accommodate a wide range of missions that may face future naval operations. The Knifefish UUV, which is intended for deployment from Navy vessels such as the Littoral Combat Ship, is based on the General Dynamics Bluefin Robotics Bluefin-21 deep-water autonomous undersea vehicle).

So concisely, what is unique about the KnifeFish platform?

Two things. I’ve already told you that we have brought it to where it is a producible, usable, reliable – and at a price point – that nothing else is (at).

So now we are talking KnifeFish as opposed to BlueFin 21. KnifeFish is designed so that the coupling between the payload – which is a Navy-designed payload – and the product is unique. The hydrodynamics, the acoustic properties of the unmanned vehicle, are extremely well-matched to the needs of the sonar. And with the signal processing we are capable of delivering, it’s a combination that isn’t easy to replicate. This is really understanding the physics of how the sonar interacts with the UUV. We are able, and have proven, mine detection performance that has never been seen before. So it’s much more than just making it reliable, producible and inexpensive (but those are really important, too!). The KnifeFish takeaway: It’s so easy. It just works. You put it in water, you tell it what to do, it goes and it does it, it comes back, you recover it, and it feels solid and repeatable.

We talk about individual systems, we talk about holistic systems and solutions from the land, the air and the water. How specifically does General Dynamics view and drive this multi-platform connectivity?

It is a really good question, but let’s step away from UUVs for the moment. I told you kind of the scope of the business that I run, and one of the things that you learn as you get more into solving mission problems is eventually it’s about the data: the sharing of data, the data fabric that allows you to communicate among land, air, sea, space. How reliable is that data? How secure and cyber-secure is that data?

So cross-domain data sharing is a big deal. We are putting real energy there and it’s not just UUVs. It’s exploiting data fabrics that were developed for ground systems to put them into our UUVs so that we can really, intelligently share information from a submarine to a UUV, to maybe an unmanned surface vehicle, and relaying up to a satellite and back down to some other effector. That’s a big deal.

We have “an explorer business” that takes what you know, your organic business, but it looks way out of the box? We have a great out-of-the-box thinker, an undersea expert, and we’ve chartered him to go with a small team and really work on how to take our UUV business, our command and control business for submarines, our undersea-cabled business, and put those things together in intelligent ways to solve our more complex, higher end problems. I think this question is as vital as any of the ones that you asked, because I think that’s where this market goes for the military. It’s about making the UUV useful – not making it work.

We live in an increasingly connected world, where cyber threats and cheap-to-produce asymmetrical threats are the norm. Can you put in context the growing cyber threat?

Let’s put a caveat around the whole thing: anything associated with cyber security starts to get pretty sensitive pretty quick.

… Understood …

One of General Dynamics Mission Systems’ six businesses is called Cyber and Electronic Warfare Systems. That’s all they do, and that business is enormous. So we work extremely closely. Of course, that gives us access to products and to experts that are dealing with the modern cyber threat. In the case of the UUV, I think you could, as a minimum, rapidly get your head around categories of threats – there is nothing particularly sensitive about that. But imagine that you have a supply chain threat; we have that in everything that we build. Unless you absolutely control your supply chain all the way down to the foundry, there’s always going to be some risk that there is some cyber threat inherent in any product that you buy.

There’s the insider threat: Somebody using the UUV would have that intent. The UUV itself is a unique thing: you send it out to do its job, and it’s now out of your sight. When it comes back, how do you know what’s happened? And then we have the other complication that is shared by all military assets that communicate, which is what is your defense of your cyber, of your comms? So we look at all of these categories of challenges. We work closely with the Navy and with other agencies to try to understand them, assess them, mitigate them. I would call GD “experts” – truly experts – in this. Having said that, it’s one of the toughest challenges that we face.

One final question. If you had to pick the area of the greatest focus of investment from a technology standpoint, or a product standpoint, where is it in 2018 and beyond?

I think I started to tip my hand on this when I was outlining the different diameters of vehicles. Having successfully come through the productization of Sand Shark, and the productization of our 21, we’re finishing the productization of the 9 and 12. They are for sale now, but we’re really taking that holistic look at making them the absolute best that exists in those diameters. That’s a pretty big focus, we’re right in the middle of that, and that will take us through the bulk of 2018.

On the other hand, we have a very rich technology roadmap and it has all the things you might expect and maybe some that you don’t. It is things we’ve talked about today – cyber security, autonomy, energy, propulsion, miniaturization and signal processing.

And by the way, you know a term we haven’t used at all – open architecture. That has been and is our mantra and we are very genuine at that. It means that we like standardization, modularity, and we don’t have to own all of those technologies that we use. We’re happy to work with industry. If somebody’s got a better mousetrap, an autonomy algorithm that really works for us, a signal processor, a GPS receiver, a battery – we want to scour the world and be great buyers and great partners.

And I think that we’re still in a phase in this market where the market is growing, and so you see people more as teammates than competitors. That’s really positive – it creates a lot of energy in the marketplace and I think it advances the technology at a much quicker pace.