SUBSEA ENGINEERING: By-pass, superfast

When a troublesome pipeline beset with wax issues escalated into a blockage, new North Sea independent Chrysaor and Subsea 7 nimbly dealt with it, installing a 26km bypass pipeline in just eight months – despite facing multiple issues on the way.

Chrysaor is a new operator on the UK Continental Shelf. Only about 18 months old, it’s got growth ambitions, after first acquiring a package of assets from Shell in 2017 in a $3.8 billion deal.

But, acquiring existing producing assets can come with issues, including that they’re older, complex, interconnected and have been through multiple owners and therefore might not come with complete records – including exactly where and what diameter pipelines are.

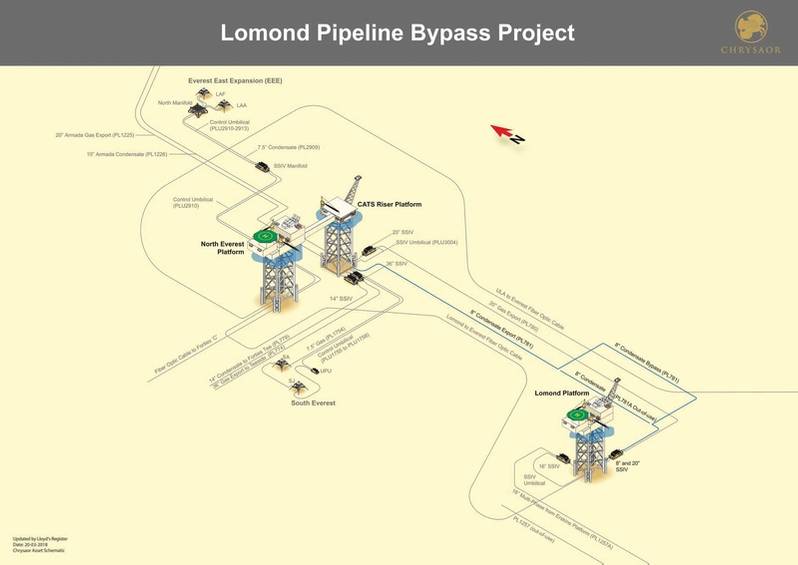

The Lomond platform (initially operated by Amoco, BP, BG Group and then Shell) sits 145m east of Aberdeen in 83.8m water depth and started producing in 1993. Gas condensate from the Erskine facility, operated by Chevron, is exported to the Lomond platform and then 57.8km on to the Everest platform for onward export via the CATS system into the Forties Pipeline System to shore.

When Chrysaor took on Lomond as part of its acquisition of (ex-BG Group) assets from Shell in 2017, it knew there was a history of blockages in the Lomond to Everest condensate line, due to wax dropping out of the condensate flow as it cooled. While condensate from Erskine is transported through an insulated pipeline from Erskine to Lomond - stopping it falling to temperatures where wax forms - the Lomond to Everest pipeline isn’t insulated.

“As it leaves Lomond, where the line is not insulated, as soon as it falls below 48°C the wax falls out,” says Emily Eadington, Wells & Subsea Projects Manager, at Chrysaor. “When the line was installed in 1992, there were only Lomond fluids to transport, so wax was not an issue, thus no insulation.” In 1997, Erskine condensate was added, and in order to mitigate potential wax-build up, a strategy to pig the pipeline every two weeks was developed. “But, it was last pigged in 2009. When we took it over, you couldn’t put a PIG in because the PIG could get stuck.”

Navica Pulling Head welding onto Stalk #1. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

Navica Pulling Head welding onto Stalk #1. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

Chrysaor needed to clear the pipeline before it became blocked again. But, clearing it might not be that easy. “There was a debate if we should clear it or bypass it,” says Eadington. “We decided to just try and carefully maintain flow rather than unlock it and, in the meantime, put in a bypass pipeline as the chances of it blocking while we were trying to unblock it were 50%.” So, late 2017, while the pipeline was still flowing, Chrysaor started engineering work with Subsea 7, which had previously performed engineering on a solution for a bypass pipeline under a previous owner operator.

Then, in January 2018, the very day Chrysaor secured partner (Chevron and Serica Energy) agreement to invest in the bypass pipeline, the Lomond-Everest pipeline became blocked. The project’s urgency was now escalated. What would normally be an 18-month project needed to be done as quickly as possible.

“We went into fast-track mode,” says Eadington. “We didn’t have a construction contract in place and were working quickly as a small team. We didn’t want to man-mark Subsea 7’s team to see what they were doing, so we put it in their hands.”

“The partnership started at that point,” says Alan Fyfe, Project Manager, Subsea 7. “We didn’t have a written specification or scope of work that you would normally get with an EPCI (engineering, procurement, construction and installation) contract. The agreement developed as we went. We had the background work we had already done. We discovered issues en-route and we worked around them.”

The original plan was to lay a new pipeline, shut down the still operating pipeline, flush it, then cut the ends of the existing pipeline to before where wax drops out to after the blockage, and connect in the new pipeline. Simple, in theory – anything flushed out would be sent on to CATS for treatment. With the pipeline blocked, flushing it out with a blockage in the middle was no longer so simple – fluids at the Lomond end would have to be flushed back to Lomond, which wasn’t designed to receive fluids. This meant hot tapping the existing pipeline so the contents could be flushed back to Lomond and to CATS on the other side. In addition, a temporary pumping and filtration spread had to be set up to divert the flushed fluids back over Lomond and into the Erskine pipeline for temporary storage.

Offshore work started in mid-June, when the dive support vessel (DSV) Sevan Seven Eagle was sent in to find the existing blocked pipe. Having probed at the location where Chrysaor’s inherited documentation suggested it should be, it was finally found some 4 4m away.

Mid-July the DSV Seven Pelican came in to do more preparation and hot tap work – i.e. tapping into the existing pipeline either side of the blockage to enable access to, first, run in barrier gel to isolate the wax section and then flush out any remaining hydrocarbons and towards CATS and back to Lomond.

Reel Walking. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

Reel Walking. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

From late July, the Seven Navica pipelay vessel laid the new 26km-long 8in pipeline - fabricated and spooled at Vigra spoolbase, Norway - and performed metrology for the spool piece construction, which had already started and ran through to the end of August. The original plan was to use the Seven Borealis for pipelay. But Subsea 7 decided that it could bring the Seven Navica out of cold stack in Leith, near Edinburgh, to speed up the schedule and do metrology works while it was on site.

The tie-in points were at Lomond, where there was a subsea isolation valve, which meant a relatively simple flange connection. At the other end, where the existing pipeline had been dredged out, to be cut, the pipeline’s concrete coating had to be removed, then the pipe cut in order for the diver-installed mechanical connectors to be installed. As this work was being carried out it was discovered that the 8in pipeline was not the diameter expected. This was important in order for the connectors, construction of which had started already, to fit. Luckily, the connectors were able to be modified.

Once the new section of pipeline was installed, it was flooded, cleaned and gauged subsea, to check it clear of any damage, then inspected externally using an ROV. In August, the new pipeline was trenched in and the DSV Seven Falcon came into the field to flush and cut the pipe. Finally, the Seven Eagle returned to install spool pieces, which connect the new pipe to the ends of the old pipeline, completing its work in mid-late September. The system was ready on September 22 and production restarted on September 30 – just eight months after the project launched.

For both Eadington and Fyfe it was a project which faced challenges, hit problems and was dependent on subcontractors delivering. “We didn’t get it right all of the time, but enough of the time and very few things didn’t work for us,” says Eadington. “Most of the suppliers delivered on time, but when there was a delay we found time in the DSV schedule to make things happen and we got there faster as a result,” says Fyfe. “If we had planned the project, there would have been fewer campaigns. But, doing it when we had vessels available meant we got the job done faster.” Eadington adds: “a big gain from a schedule perspective was that Subsea 7 was able to accommodate changes as the project gained complexity and propose solutions.”

An advantage was also was that Chrysaor, as a small organization, was able to be nimble. When issues arose, those dealing with them were able to make decisions and run with it there and then.

“It was a real challenge, but it was great to be involved and solve it,” says Fyfe. “The project team in Subsea 7 was recognized for their work as a team but the reality is the team included Emily and her colleagues as well and there was very little demarcation in a client contractor sense. We weren’t being man-marked. We had a common goal.”

Lomond Pipeline Bypass Project Schematic. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

Lomond Pipeline Bypass Project Schematic. Images courtesy Chrysaor and Subsea 7

Read SUBSEA ENGINEERING: By-pass, superfast in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 2019 Marine Technology

Other stories from April 2019 issue

Content

- AIS Data: History & Future page: 10

- DOLPHIN: Enabling Technology for Acoustic Systems page: 20

- Unheard Underwater: Covert Communications page: 26

- World Navies: Brazil´s Riachuelo Submarine page: 34

- French Frigate Sonars Get an Upgrade page: 38

- Efficient Wave-Generated Power … Really! page: 40

- SUBSEA ENGINEERING: By-pass, superfast page: 48