The Riskiest Places to do Business – and Why

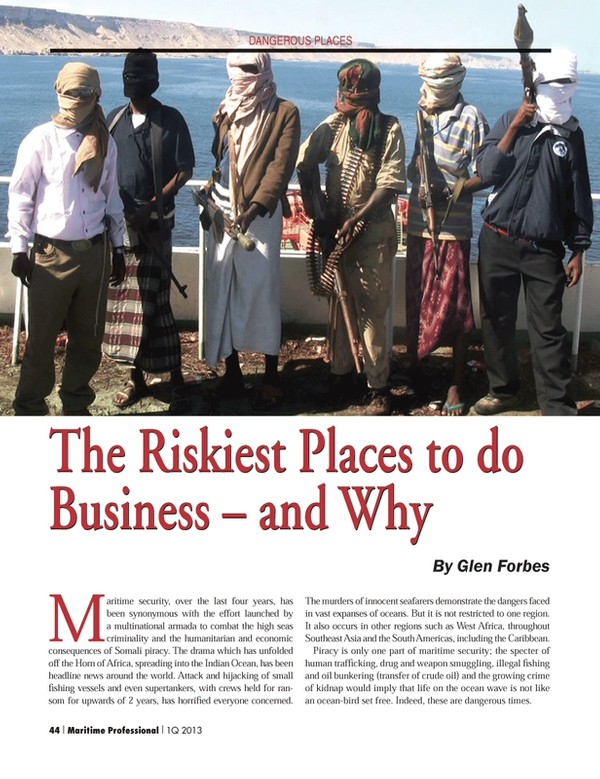

Maritime security, over the last four years, has been synonymous with the effort launched by a multinational armada to combat the high seas criminality and the humanitarian and economic consequences of Somali piracy. The drama which has unfolded off the Horn of Africa, spreading into the Indian Ocean, has been headline news around the world. Attack and hijacking of small fishing vessels and even supertankers, with crews held for ransom for upwards of 2 years, has horrified everyone concerned. The murders of innocent seafarers demonstrate the dangers faced in vast expanses of oceans. But it is not restricted to one region. It also occurs in other regions such as West Africa, throughout Southeast Asia and the South Americas, including the Caribbean.

Piracy is only one part of maritime security; the specter of human trafficking, drug and weapon smuggling, illegal fishing and oil bunkering (transfer of crude oil) and the growing crime of kidnap would imply that life on the ocean wave is not like an ocean-bird set free. Indeed, these are dangerous times.

Somalia, Horn of Africa & Indian Ocean

Somali piracy, from 2008 onwards, grew to unprecedented levels in the following years. In the vacuum of effective shore-based governance, the clan rule across Somalia and the feared Islamic militants with the long-term humanitarian dilemma of displaced persons, the scourge of piracy took hold. In seeking to protect World Food Program relief efforts, NATO, EU and Combined Maritime Forces, along with other international navies, began escorts and monitoring of commercial shipping transiting the region, within the Gulf of Aden (GoA). As international efforts to stem the tide of piracy centered on the GoA, ever resourceful the pirates spread across the Indian Ocean and changed tactics to use previously hijacked vessels as motherships to use in attacking other larger vessels.

Naval operations evolved to include convoy escort, transit corridor and vulnerable shipping protection; boarding and search of suspect vessels, patrols closer to the Somali coast and eventually authorization for a land-based attack. Special Forces operations to rescue humanitarian workers and seafarers have been conducted, however, the fear of causing fatalities or resulting in recriminations against hostages has made this option one of high risk. At the lowest point for seafarers, more than a thousand sailors were held hostage by pirates.

The shipping industry did not sit back and expect the military authorities to be everywhere and anywhere piracy may occur. Taking the initiative, they collectively established Best Management Practices as a guide to shipping companies and operators in better protection of vessels and crew. Tellingly, after initial misgivings, private maritime security companies (PMSC) became a staple method of protecting shipping. Whilst not permitted by every flag state, armed security teams are more prevalent but international standardized practices are rather more difficult to come by, and the rules for the use of force by commercial security is a sticking point for all.

There are a few aspects that are not directly related to the threat in this area, but nevertheless, have an impact on piracy. The newly-elected Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) has been recognized by the USA, and subsequently, the improvement of law on land is seen as developing along the right road. Add to this situation the long-running fight against the Al Qaeda-based Islamic militants, Al Shabaab and then the potential for a convergence between them and the pirates. The kidnap of humanitarian aid workers from displaced person camps (food shortages remain a major problem) and journalists should not be overlooked either. If the international forces are reduced due to the perceived successes in combating piracy, then there is every possibility that piracy could see resurgence in yet another vacuum. Without a doubt, the situation today is fragile and reversible.

Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea (GoG) has seen resurgence of piracy incidents in 2012 as piracy, or alternatively robbery at sea, has shifted around the region. Omitting Nigeria from this particular equation, the attacks have varied from robbery of crew personal items whilst the ship is anchored or in port, to hijack for the fuel cargo in the prevailing illegal oil trade. The attacks in ports and anchorages of Togo, Guinea, Ivory Coast and Benin have seen more a violent approach during such incidents. In some cases, port authorities have not responded to distress calls made within the areas.

Nigeria

The challenges to maritime security off Nigeria are beginning to overshadow that of Somalia. The main difference between East and West Africa is that the attacks have taken place in territorial or Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) waters of the nations surrounding the GOG. Nigeria-based criminal gangs dominate the illegal oil syndicates in the country and the bunkering of oil from tankers in the GoG. Despite a 2009 amnesty, piracy (or robbery at sea) has increased but with lessons learned from the Somali model in the use of motherships, kidnapping, the Southeast Asia model of hijack for fuel cargo, destruction of communications and navigation equipment, and then release. Furthermore, as Nigerian forces increased efforts in local waters, pirate gangs moved to the less protected waters of Togo and Benin and on towards Ivory Coast. With illegal oil refineries in the creeks of Nigeria, kidnapping ship crew for ransom, the insurgents, Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) are able to hide their hostages in the jungles of the state. Subsequently, the attacks have become more violent. The Joint Task Force in Nigeria is making inroads in arresting the gangs, however, global criminal networks and corrupt officials connected to a multi-billion dollar industry mean that the phenomenon is not likely to be reduced any time soon. West African nations have viable governments, unlike Somalia, until recently; therefore UN and international navies are unlikely to become involved to the same degree as off East Africa. North Africa, however, may see maritime security come under closer scrutiny as threats develop around Yemen, Eritrea and the upheaval in other states over the last year.

Southeast Asia

Security in this region is increasingly dangerous. A common problem is petty theft from ships off Indonesia whilst pirate boarding and hijacks continue to plague the region with little let up to date. Vessels are hijacked and renamed for illegal use, taken for oil cargo, and hostages are often taken during these acts – kidnap for ransom is less prevalent. The Malacca and Singapore Straits also remain common grounds for piracy. The East China Sea and South China Sea are experiencing crises and dilemmas that threaten to spiral out of control as claims to territory and natural resource rights are often at the center of disputes in the region, particularly between China and Japan – an escalation of reprisals that may see retaliations not witnessed for many years as other states are drawn into the situation.

The disputes over fishing grounds regularly result in the opposing nations’ coastguards arresting fishermen by the hundreds each year. The pirate groups in the Bay of Bengal kill over 50 fishermen and injure many more each year; however, as it is seldom international commercial shipping, little is heard.

Looking Back ... and Ahead

The prospect of being taken hostage or losing a ship through hijack has greatly diminished over the past 12 months. Security issues continue to include increased violence against seafarers, the potential for attacks around ports and the level of possible conflict between nations – particularly in SE Asia – on the rise. Oil theft remains a global phenomenon at sea and ashore, and with the growth of global oil and gas resource exploitation expected in the next three to five years. There is ever more likely that this will become an even greater challenge to maritime security. Piracy and robbery at sea may evolve, but the naval forces aligned against them may not be in an economically viable or sustainable position with which to combat the issue, despite the likely revenue losses.

The absence of internationally coordinated efforts, regional maritime awareness training, and appropriately common international laws and regulations results in human and drug trafficking, piracy prosecutions, possible terrorism, illegal fishing and any arrests falling short of acceptable standards. Instead of recommendations and strongly advised actions, mandatory and lawful regulations are necessary to support the desired maritime security for trade and development which, although not understood by all consumers, has a global impact.

(As published in the 1Q edition of Maritime Professional - www.maritimeprofessional.com)

Read The Riskiest Places to do Business – and Why in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of Q1 2013 Maritime Logistics Professional

Other stories from Q1 2013 issue

Content

- Reduce Boatbuilding Risk by Starting with Requirements page: 16

- Insights: Maritime Mergers and Acquisitions - All About Risk page: 20

- Risk Breakers: Henrik O. Madsen CEO, DNV page: 24

- Risk Breakers: Giuseppe Bono CEO, Fincantieri page: 26

- Risk Breakers: Craig Perciavalle President, Austal USA page: 28

- Risk Breakers: Anthony Chiarello, CEO, TOTE Inc. page: 30

- 100% Container Scanning in Ports: It is Possible page: 34

- CMA CGM - Showing the Way Forward page: 40

- The Riskiest Places to do Business – and Why page: 44

- LNG as the Ultimate Solution? Not so fast … page: 48

- Costa Concordia & Maritime Error Management page: 53