MLC 2006: Consolidating, Costly and Confusing

An expensive new Convention, ratified and now in force, brings many things to international shipping and, in exchange, promises to take away much from the bottom line. What will it mean to you and your operations? MarPro contributor Gary English helps to sort it all out.

The Maritime Labor Convention (MLC) of 2006 is a product of the International Labor Organization (ILO), which aims to provide a consolidated legal framework governing the rights of seafarers, updating and supplanting previous applicable international conventions.

The MLC 2006 constitutes the “fourth pillar” for the International Maritime organization (IMO). Together with SOLAS, STCW and MARPOL it aims to ensure that safe, environmentally friendly quality shipping is established, maintained and constantly improved. Speaking at a recent NorShipping event in Oslo, the Chairman of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), Masamichi Morooka, said that the weight of the impending new legislation potentially presented an additional industry-wide cost of more than half a trillion US dollars between 2015 and 2025. This is around 50 billion dollars of additional capital and operating cost in every single year for a 10-year period and beyond. MLC, of course, is only part of that cost.

Simply stated, the MLC 2006 creates a framework of rights to support uniform working and living conditions for seafarers, and ensures equal conditions of competition for shipowners. MLC 2006 brings together the majority of the existing maritime labor instruments into a single Convention and replaces the current international law on all of these matters.

The Convention was ratified with the submission from the Philippines being lodged with the ILO on August 20, 2012, meeting the criteria of 30 states representing at least 33% of the world’s tonnage ratifying the Convention. Therefore, MLC 2006 came into force 12 months later, on August 20, 2013, and applies to all Member States. The United States has not ratified MLC 2006 and likely will never do so. That doesn’t mean that U.S. operators won’t have to comply when trading in international waters. They will.

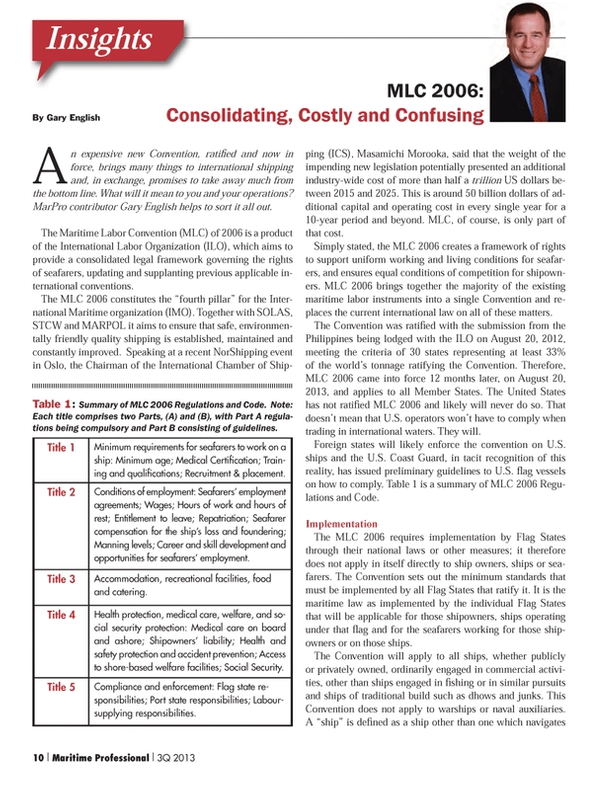

Foreign states will likely enforce the convention on U.S. ships and the U.S. Coast Guard, in tacit recognition of this reality, has issued preliminary guidelines to U.S. flag vessels on how to comply. Table 1 is a summary of MLC 2006 Regulations and Code.

Implementation

The MLC 2006 requires implementation by Flag States through their national laws or other measures; it therefore does not apply in itself directly to ship owners, ships or seafarers. The Convention sets out the minimum standards that must be implemented by all Flag States that ratify it. It is the maritime law as implemented by the individual Flag States that will be applicable for those shipowners, ships operating under that flag and for the seafarers working for those shipowners or on those ships.

The Convention will apply to all ships, whether publicly or privately owned, ordinarily engaged in commercial activities, other than ships engaged in fishing or in similar pursuits and ships of traditional build such as dhows and junks. This Convention does not apply to warships or naval auxiliaries. A “ship” is defined as a ship other than one which navigates exclusively in inland waters or waters within, or closely adjacent to, sheltered waters or areas where port regulations apply.

Table 2 below is a summary of nominal procedures for obtaining a Declaration of Maritime Labor Compliance Certificate (DMLC). All new ships flagged in a Member State that are constructed after the Convention comes into force must be built to meet the requirements of the Convention. Attention must be paid in particular to accommodation areas, where more space may need to be set-aside for the crew. Ships built before the Convention comes into force are required to comply with existing requirements of the Flag State.

Under the Convention, shipowners will be liable for costs in relation to illness, injury or death of crewmembers occurring during their duties on board. The provisions are quite wide in application. The exceptions - if enacted by Members in national laws - would be limited to situations where;

- Injury occurred otherwise than in service of the ship;

- Injury or sickness was due to willful misconduct by the seafarer concerned; or

- Sickness was intentionally concealed when the seafarer was taken on by the shipowner.

The MLC 2006 will require that Flag States ensure that seafarers are entitled to:

- Repatriation, including repatriation in cases of a ship owner’s insolvency for which financial security must be in place;

- Unemployment compensation resulting from a ship’s loss or foundering. Paid for the days during which the seafarer remains unemployed at the same rate as the wages payable under the employment agreement, but the total indemnity payable to any one seafarer may be limited to two months’ wages;

- Compensation in the event of death or long-term disability due to an occupational injury, illness or hazard as set out in national law, the seafarer’s employment agreement or collective agreement and for which the ship owner must provide financial security.

In relation to the repatriation, sickness, injury or death, occurring in connection with seafarer’s employment, Flag States will have to require ships flying their flag to maintain “financial security” in respect of such claims. Financial security is not defined and the MLC does not prescribe the form or any amount of coverage. Each Flag State will require its own form of financial security in its own domestic legislation to implement the Convention. Seafarers are entitled to repatriation in the following circumstances:

- If the seafarers’ employment agreement expires while they are abroad or is terminated by ship owner or seafarer for justified reasons or when the seafarer cannot carry out his duties or be expected to carry them out under specific conditions;

- In the event of illness or injury or other medical condition which requires repatriation when found medically fit to travel;

- In the event of a shipwreck;

- In the event of the ship owner not being able to continue to fulfill their legal or contractual obligations as an employer of the seafarers by reason of insolvency, sale of ship, change of ship’s registration or any other similar reason;

- In the event of a ship being bound for a war zone, as defined by national laws or regulations or seafarers’ employment agreements, to which the seafarer does not consent to go; and

- In the event of termination or interruption of employment in accordance with an industrial award or collective agreement or termination of employment for any other similar reason.

An important question will be whether a standard P&I Certificate of Entry (COE) will be sufficient for the purpose of establishing that the required financial security is in place, to meet MLC 2006 standards. While some parties to the negotiations of the MLC 2006 considered such COEs sufficient, the MLC 2006 does not define what is suitable ‘financial security,’ and it will be up to individual States to decide what may be required. What may play in Peoria, then, might not be good enough in Hong Kong. While this may not be controversial for illness, injury or death arising from work on board the vessel - matters typically covered under P&I insurance - more challenging may be the issue of security for the costs of repatriation of abandoned crew.

The abandonment of the crew by a shipowner in financial difficulty is a matter that has always caused great concern. In these difficult economic times, it is likely to continue to be a challenge facing seafarers. Given that this circumstance typically arises from the bankruptcy of the shipowner, it is something that has to be addressed further, as the consequences of bankruptcy are not always a straightforward insurance matter.

Finally, many of the terms used in MLC 2006 are arguably vague, making it difficult to assess how to set a standard regulation. For example, words like ‘adequate’, ‘reasonable’, ‘suitable’ and ‘appropriate’ are capable of producing a wide range of interpretations.

Equally, it will remain to be seen exactly how a particular Flag State incorporates the Convention’s regulations into national law. There is a real possibility of significant differences arising between different interpretations and becoming enacted in national legislation/regulation of Member States. Therefore, it will be critical for each shipowner to closely monitor how their Flag State incorporates MLC 2006 into their national statutes and regulatory schemes.

(As published in the 3Q edition of Maritime Professional - www.maritimeprofessional.com)

Read MLC 2006: Consolidating, Costly and Confusing in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of Q3 2013 Maritime Logistics Professional

Other stories from Q3 2013 issue

Content

- Editor's Desk: Unconventional Progress page: 8

- MLC 2006: Consolidating, Costly and Confusing page: 10

- An Unarmed Approach to Piracy page: 14

- Maritime & Offshore M&A page: 16

- A Chat with Capt. Eric Clarke page: 20

- Handicapping Harvey Gulf page: 24

- Riding the Wave page: 30

- Pioneering LNG on the Great Lakes page: 40

- Performance-Based Assessments page: 44

- Why We Test for Drugs & Alcohol page: 50

- Meeting MLC – and More page: 54

- MLC 2006: Will it Drive Crew On Board Comms? page: 60

- MLC 2006 & You page: 62