Northwest Seaport Alliance: Innovative, Ideally Located and Together as One

By Joseph Keefe

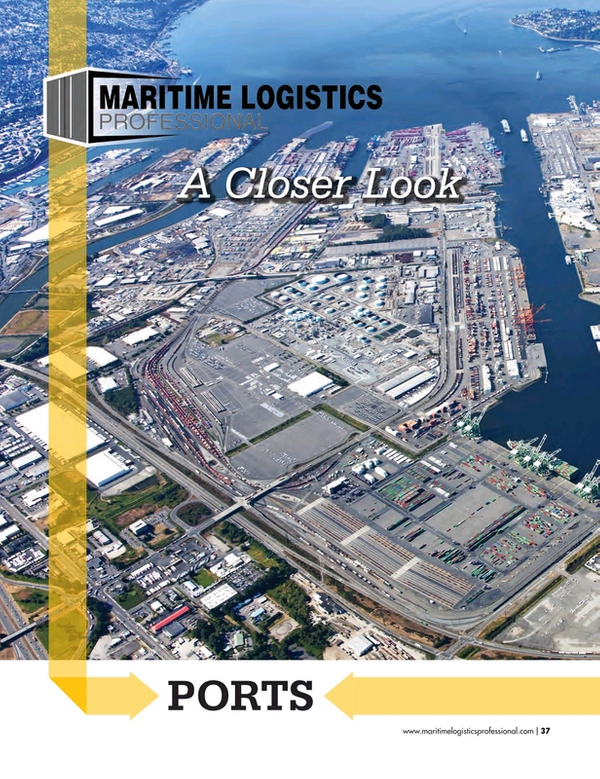

Located in the Pacific Northwest in Washington State, The Northwest Seaport Alliance joining the deep draft ports of Seattle and Tacoma offers shorter U.S.-to-Asia transits, as well as a deep connection to Alaska. And, a lot more.

In an era where the fiercely competitive business of global trade is changing in ways that could not have been imagined just one decade ago, ports, terminals and their collective stakeholders are rethinking how to also remain relevant. Shifting liner alliances, an uncertain regulatory climate, the expanded Panama Canal and the possibility of changing trade agreements mean that the status quo won’t be enough anymore. On the U.S. West Coast – Washington state, to be precise – that’s already become only too obvious.

Located in the Pacific Northwest in Washington state, The ports of Seattle and Tacoma, formerly two separate and diverse entities, compete with everyone else for market share. Until recently, they competed against one another, as well. That all changed in August of 2015 when the two formed what is now known as the Northwest Seaport Alliance (NWSA). That’s not to say that the two ports didn’t collaborate in certain ways prior to that. They did. Today’s NWSA, however represents something far more powerful and in an era where political leadership fails to meet in the middle for the common good, this is one instance where the so-far one-of-a-kind relationship is already yielding fruit.

The Northwest Seaport Alliance

The Northwest Seaport Alliance is a marine cargo operating partnership of the ports of Tacoma and Seattle. The first of its kind in North America, the NWSA is the nation’s fourth-largest container gateway. Regional marine cargo facilities also are a major center for bulk, breakbulk, project/heavy-lift cargoes, automobiles and trucks. Specifically, NWSA is designed to deliver less congestion, closer proximity to Asia deep ties to Alaska, and an easier way of doing business. Naturally deep-water harbors and the ability to handle a wide range of cargo position it collectively as the ideal gateway to meet the growing needs of Pacific Rim trade.

Uniquely, the alliance, whose boundaries include King and Pierce Counties, is a port development authority governed by the two ports as equal members, with each port acting through its elected commissioners. The overriding goal is to gain a collective competitive advantage for all international trade, while maximizing unrealized potential for both ports. And while the value of this two-way international trade totaled more than $73 billion in 2014, including $18 billion in exports, both ports know that they can and should do better.

John Wolfe is the chief executive officer of The Northwest Seaport Alliance. He sets the organization’s vision, and guides the NWSA’s unique dual port, customer-focused culture. He also serves as the CEO of the Port of Tacoma, a position he was named to in 2010. Boasting deep roots in the port management business, he spent 10 years with Maersk Sealand/APM Terminals in Tacoma, most recently as the terminal’s operations manager. He knows the region and more importantly, what it needs to compete in today’s changing intermodal landscape.

For the Greater Good

NWSA CEO John Wolfe told MLPro in July, “For decades, the Ports of Seattle and Tacoma have cooperated, much like Los Angeles and Long Beach, in areas such as the environment, security, and safety. We also competed primarily for international container business. Other than that, the two ports have different business areas of focus.” In some respects; quite different. For example, Seattle owns and operates SeaTac Airport. Tacoma doesn’t own or operate anything like that.

What they did have in common was the quest for the international container business. “That’s been okay, and yet, as you know, the industry has gone through significant change in a short time frame,” explained Wolfe, adding quickly, “we felt the effects of that change as a gateway, being now the fourth largest gateway in North America for container trade. From a strategic standpoint, it was better that we work together than compete here within Puget Sound.”

Through a series of conversations between the two commissions, they came up with the structure which is now referred to as the Northwest Seaport Alliance. A 50/50 joint venture ownership, it is its own company; recognized by the Federal Maritime Commission. Today, the joint venture seeks to pool collective assets, financial capabilities and strengths together as one gateway, focusing on how best to create solutions for Puget Sound and its customers.

NWSA governance structure is driven by state law. Separately, the two commissions are elected by the counties they serve, with five commissioners in both Seattle and in Tacoma. Wolfe notes that the Alliance did not change the governance structure of the ports when it was formed. “As it relates to the business of the seaport alliance, we have meetings where both commissions are present together, and when we bring forward any capital investments or major leases that are outside management’s decision-making authority, they take action on those as two boards. A simple majority of both boards moves that request forward.”

It is important to define what the Alliance is, and what it is not. The Seaport Alliance is not a bank – the home ports are the funding entities for the Seaport Alliance. As an example, and when they collectively bring forward a major ($100 million) capital expenditure for an improvement to assets in either port, both boards then vote, and assuming that there is approval to move forward with that project, what they’re committing to is 50 million dollars from each port to that investment. Ultimately, though, the net operating income is split 50/50 back to the home ports to pay off that investment and to reinvest back into the business.

Unique Solutions for Difficult Challenges

The NWSA arrangement came about in August of 2015 – a watershed moment for the gateway and the ports themselves. For Wolfe, the concept is a simple one, built on trust and mutual agreements. “Everybody benefits. It’s as though, from a management standpoint and a funding standpoint, we are one gateway. And we’re indifferent about where those investments are made, and where the cargo resides, and where the income comes from, as long as it is aligned around and interested in growing the business and the financial resources as a gateway.”

Before the Alliance, Seattle had their business and investment strategy to grow their container business, and Tacoma had one of their own. To that end, and given the softness of the market extending into the previous decade, it wasn’t always the best strategy for two deep draft ports coexisting in such close proximity. “Oftentimes,” says Wolfe, “Seattle would make an investment, Tacoma the same, and we would duplicate that investment, creating more capacity than the demand existed for the gateway.” This usually involved competing on rates to do that. As a direct result, even the port that won the business might struggle to make it work.

Wolfe says it best, insisting, “By stepping into this partnership, we’re able to have a single investment strategy for the gateway and reduce any risk of over-investment and really be more strategic about where our investments are going to be made, aligned with our customers’ interest, and really, a better balance of the supply/demand curve within the gateway which provides compensatory levels of rates not just for us, but also our tenants, the terminal operators that operate, and provides a better service to our customers.” Wolfe also pointed out that if the terminal operator is losing money, they’re not apt to spend money on service delivery improvements.

It can be a delicate balancing act. Even with all the local collaboration, Seattle and Tacoma – and their respective ports – are two very different entities. The more urban Seattle port primarily involves the international container business. Tacoma, on the other hand, consists of a broader mix of international as well as domestic container business, but also break bulk, RO/RO, and bulk products.

That reality, says Wolfe, required a whole new business plan. “And so we have a collective strategy now in the North Harbor, where our primary focus is going to be – is and continues to be – to have the international container business at Terminal 18 and future Terminal 5 with a major capital investment, and then repurposing some of the other facilities for industrial use. So we really strengthened our position in the North Harbor that way.”

Seattle’s Terminal 18 is a large, international container terminal, able to serve the largest vessels in the trade. Indeed, CMA CGM’s Benjamin Franklin called here last year, and the terminal is capable of handling up to 18,000 TEU capacity vessels. “We’re not duplicating and creating more international container terminals than what we need,” said Wolfe.

Similarly, that investment is balanced by planned investment in the South Harbor. And, that collective strategy takes into account the gentrification piece – something that all ports are facing. “We’re aware of that for both Seattle and Tacoma, what is occurring, in a better way, is further engagement with the broader community and the city government to have proper land use planning, and aligning ourselves around that land use planning so that we don’t create for ourselves these conflicting interests. Engagement with the City of Seattle and City of Tacoma is really important.”

Leveraging Local Strength

A key strength of the gateway, and one that is an important selling point for it, is that not only do the local ports not have to deepen their waterways, they also don’t have the ongoing maintenance requirement to maintain that water depth on a regular basis, whereas some of the major ports around the country are still struggling with it – especially in a post-Panama Canal expansion environment. With that advantage also comes challenges, though. And, to that end, the dredging situation is something that NWSA has been addressing within the Ports Association and at the federal level.

Wolfe laments that importers that use the NWSA gateway also pay into the Harbor Maintenance Tax, and yet, the local ports don’t have a need for the use of that fund. “Arguably,” insists Wolfe, “We’re helping to fund competition through that Harbor Maintenance Tax. And, in addition, the importers that use the Canadian gateway – say, the Port of Vancouver, British Columbia – they can avoid paying that Harbor Maintenance Tax and put that container cargo on the Canadian railroad and run it into the United States and, again, avoid the Harbor Maintenance Tax. So we feel like there’s a need to revisit the Harbor Maintenance Tax, especially with the changes in the industry. We’re having those types of discussions, as well.”

The Alliance also has the unenviable task of competing not only with domestic U.S. West Coast ports, but its Canadian neighbors, located a stone’s throw to the north, as well. In Prince Rupert Sound, BC and beyond, Canadian ports have not been sitting on their hands. There, a modernization program is nearing completion. Moreover, the Canadian intermodal relationship is exceptionally strong, with trucking, ocean liners, terminals, and rail all recognizing that each mode is only as strong as the one that precedes or follows it in the intermodal supply chain. Wolfe and his NWSA colleagues are only too aware of this.

“When we formed the Seaport Alliance, we stood up an Executive Advisory Council, where the key partners in the logistics chain meet formally once each quarter, with the sole purpose of identifying inefficiencies in the movement of cargo through our gateway and reducing those inefficiencies. Imagine sitting at the table – the port, the shipping lines, the terminal operators, our labor partners, the railroads, the trucking companies, the warehouse distribution companies – talking about how things work today and how we can improve upon the efficiencies and reduce inefficiencies of the gateway. That’s working pretty well. There are some key initiatives that have surfaced as a result of that and then there are smaller breakout groups that work those issues and bring them back to subsequent meetings.”

NWSA went the additional mile and established metrics of performance, measuring against those activities and looking for constant improvement, whether it be on crane productivity, gate turn times, dwell time, total transit time from Seattle-Tacoma to Chicago, and a raft of similar measurable benchmarks. “That’s one area of focus that we’ve stepped up our game on,” adds Wolfe.

Another more tangible manifestation of the NWSA partnership is their new operations center, one which has coverage over both harbors. Its focus is on day-to-day operations and real time response to issues that come up on a day-to-day basis, whether a terminal has a congestion problem or perhaps a delay because there is an accident out on the highway. The center allows for real-time communication with key stakeholders, guided by operations staff – many previously from the private sector – and who understand their customers’ business well.

In the end, the alliance seeks to compete, not just with Prince Rupert, but really all the gateways that are participants in the Trans-Pacific trade.

How is it Going?

Over the past two years, the two port alliance increased overall volumes and held onto its market share, whereas in past years, it was seeing a slow reduction of that Trans-Pacific market share. Wolfe explains, “This past full year – 2016 – we didn’t increase the market share yet we didn’t lose market share. So that was encouraging. Now, we’ve got to continue to work towards constant improvement because we can’t rest on our laurels – this year is another highly competitive year, so we’ll see how we do this year.”

But, as NWSA aspires to be ‘that gateway that is easiest to do business with,’ Wolfe also knows that they have work to do. The shift in liner alliances from four to three partnerships brought with it a shuffling of cargo at the gateway – and others, to be fair – and this created certain operational inefficiencies at some terminals. Wolfe insists that the alliance is working through all of it.

Locally, even with the sea change that has deeply impacted the liner trades, the NWSA came out about even in terms of volumes, but some of the more immediate challenges include the impact of cargo shifting from one terminal to another. Wolfe promises, “Our team is really focused in that area right now. As we improve upon that, I believe that more cargo will come our way. The other thing I would say is that we are looking for, and encouraging new ways in which our terminal operators may partner with each other. That is made easier by having all of the terminal assets under one company.” The next steps, Wolfe said, is to work in partnership with the terminal operators to look for ways in which service levels can be expanded while at the same time maintaining a price point that is competitive.

One way to do that involved the implementation and use of a new tool called DrayQ, a commercial App that helps to speed the flow of cargo along local freight corridors, reduces idling-related air emissions and saves fuel. DrayQ technology is designed to give truck drivers real-time information about wait times in and around marine cargo terminals and traffic camera views at the touch of a fingertip. Drivers can use the app to determine the best time to enter a terminal and reduce the time spent in traffic, which helps reduce air emissions from idling and saves fuel. For dispatchers or shippers, it helps to optimize schedules and improve customer expectations. That’s already yielding measurable gains, says Wolfe.

“What it does is it creates for us greater visibility to the true turn-time of a truck through a terminal. DrayQ allows us full visibility to that.”

A Look to the Future

Executing a game plan that was only developed 18 months ago, the early results aren’t necessarily easy to measure. But, says Wolfe, the Alliance needs to see that through. Among the other initiatives being considered are so-called “P3” Public Private Partnerships to help offset future port investments. Wolfe lays out the Alliance’s investment strategy by saying, “The details are still being worked through. I think the strength of the port – our gateway – is to make investment in the in-ground infrastructure, whether it’s wharfs, pavement, utilities; things of that nature. Where the private sector might come in and make their investment would be in equipment, buildings, some of the other vertical infrastructure that they need to operate.”

Separately, and with eye towards the massive – some say unworkable – Clean Air Action Plan (CAAP) which will reportedly cost the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, CA a collective $16 billion between now and 2030, we asked Wolfe how and where the Alliance was addressing the all-important issue of its environmental footprint. “We need to do the right thing,” he replied, adding, “We’ve invested just in Tacoma probably over 200 million dollars in the last 10 to 15 years to clean up some of the contamination that has existed here in the tide flats – not created by the port, created by private sector and industry back in the early years – and we have stepped up to clean up those properties. Seattle has done the same. So we have a great track record of doing the right thing from an environmental standpoint.”

Long term, the alliance seeks to align its interests with that of its customers. And, says Wolfe, the customers also want to do the right thing. At the same time, “It needs to be balanced with practical reality of the marketplace. I look at it as sort of the 80/20 rule: let’s go after the 80 percent first and attack that because that’s the biggest bang for our buck. And where the industry can do its part in that, we should, whether that’s purchasing equipment or encouraging our customers to purchase equipment that is using low sulfur diesel, or electric vehicles – and let’s look at it holistically. I think that’s a smart way to achieve an outcome that we all, in this community, want to see.”

As this edition of MLPro was headed to production, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union had just ratified a three-year extension to its contract with the Pacific Maritime Association. The vote, noted the NWSA, extends the coastwide contract through July 1, 2022. That kind of labor stability can only be a positive indicator for the near term future, especially when one considers the alternative and what has happened just a few miles to the south in Portland, Oregon. Beyond this, the Alliance also announced that it will reimburse up to $2 million to extend gate hours at its international container terminals during peak season. That kind of commitment speaks volumes as to what might come next. Whatever it is, Seattle and Tacoma will face it together, as one.

(as published in the July/August edition of Maritime Logistics Professional)

Read Northwest Seaport Alliance: Innovative, Ideally Located and Together as One in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of Jul/Aug 2017 Maritime Logistics Professional

Other stories from Jul/Aug 2017 issue

Content

- Cyber Attacks Threaten Shipping & Dominate Maritime News page: 10

- Op/Ed: Act Now on Port Infrastructure page: 14

- Today’s Maritime Security: Is the Industry Prepared? page: 16

- Global Bunkers, 2020 and Developing Market Trends page: 26

- Better Times for Box Carriers Ahead? page: 30

- Northwest Seaport Alliance: Innovative, Ideally Located and Together as One page: 37

- Addressing Today’s Shipping Challenges with Software Solutions page: 54

- Changing Box Landscape Demands That Yard Tools Keep Pace page: 58