AMERICA'S SEAPORTS The Dynamics Of Change

For more than three centuries, America's seaports have been centers of population, trade, and vibrant economic activity. Within the past three years, the U.S. seaport industry has emerged from the throes of recession, and today, in many respects, is as healthy and optimistic as it has ever been. Problems remain, to be sure. Not all of our ports have shared in the renewed prosperity. Major legislative questions still await resolution. But basically the news is good. And that is good news—not only for our ports, but for the economic regions they serve and for the national economic and security interests of the United States, as well.

The industry itself is vast, versatile, vibrant, and highly competitive.

The United States is served by 183 deepdraft commercial seaports dispersed along the Atlantic, Pacific, Gulf, and Great Lakes coasts.

Included in that number, too, are the ports of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. In 1984, America's ports accommodated just over 1.2 billion tons of cargo in the U.S. foreign, domestic ocean, Great Lakes, intercoastal and coastwise trades.

Foreign trade is essential to the United States. The United States annually exports more than 10 percent of its coal production, nearly 40 percent of its wheat and wheat flour, 35 percent of its rice, and 40 to 50 percent of its cotton. About 10 percent by value of U.S. manufacturers are also sold in foreign markets.

Equally important, exports mean jobs—American johs. Barely 20 years ago, one in 14 American manufacturing workers were engaged in making products for exports. Today, that ratio stands at one in six— an increase of 130 percent. From 1977 to 1980, four out of every five new jobs created in the U.S. manufacturing sector were export related.

America's dependence on imports is equally strong, particularly the strategic materials so essential to its national defense industries. The United States relies heavily on imported minerals—iron ore, petroleum, bauxite, natural rubber, tin, tungsten, cobalt, and manganese, for example. Imported goods and services contribute to the stocks available to American consumers.

The processing and distribution of imported goods also generates jobs and income for Americans. Moreover, selling to the United States enables foreign nations to earn the dollars they need to buy American goods and services.

Trade is important. Even more to the point, however, is the fact that more than 95 percent of U.S. overseas merchandise trade by volume and approximately 70 percent by value moves in deepdraft, oceangoing vessels. Consequently, the successful conduct of U.S. foreign waterborne commerce is vitally dependent on the services and facilities provided at U.S. seaports. For many shippers, particularly those involved in the bulk movement of coal, grain, liquids, and the like, there is simply no economical alternative to ocean transport.

Ports are also essential to national security. Major naval installations are located at a number of U.S.

ports—a number that will increase if the U.S. Navy's current strategic homeporting initiative comes to fruition. U.S. Marine Corps units are regularly rotated through the ports of San Diego and Moorehead City. Two dozen U.S. ports have been designated by the Department of Defense for use in the initial deployment and resupply of U.S.

forces abroad. A number of U.S.

commercial ports are also regular participants in military exercises, such as the annual REFORGER exercises in Europe.

Ports have had a central role in virtually every major U.S. conflict since the Revolutionary War times.

That has been particularly true in this century, when America's wars have been mostly overseas, with ports serving as staging points for the deployment, supply, reinforcement, and resupply of U.S. forces fighting thousands of miles from our shores. That pattern will almost certainly be repeated in future conflicts.

Indeed, the Joint Chiefs of Staff have stated that a major European war, sealift could bear the brunt of the workload in deployment, reinforcement, and resupply efforts. More specifically, they state: "In any overseas deployment, sealift will deliver about 95 percent of all petroleum products. That implies a need, not only for ships, but for ports to load them. And in most instances, these ships would be loaded at commercial port facilities— at terminals developed, owned, and in many instances operated by state and local port authorities.

The port industry contributes importantly to the national economy in other ways. In 1984, according to the U.S. Maritime Administration, commercial seaport activities generated $60 billion in direct and indirect benefits to the U.S. economy and contributed more than $30 billion to the U.S. Gross National Product. The stevedoring marine terminal component of the port industry alone generated $8.4 billion in revenues and salaries, and employed 138,000 persons. Altogether, seaports accounted for more than a million jobs, and billions of dollars in federal, state, and local taxes.

During the past four years, imported cargo unloaded at U.S. seaports has produced an average of 70 percent of U.S. Customs receipts from duties. That came to $6.5 billion in fiscal 1983, $8.3 billion in fiscal 1984, and an estimated $9.0 billion in fiscal 1985. A 1986 survey by the American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA) revealed, in addition, that U.S. public port authorities were providing U.S. Customs at nominal or, in most cases, at no charge, facilities and services with a total market value of just under $1.5 million annually.

© 1986, Cummins Engine Company, Inc.

The growth of ocean commerce and the revolutionary change in marine technology have placed enormous demands on U.S. public port authorities. Between 1950 and 1984, U.S. port traffic more than doubled in volume, with port handlings of imports and exports alone multiplying sixfold, reaching a peak of just over 1.0 billion tons in 1979. Fueling that growth initially was the postwar economic recovery of Europe Circle 222 on Reader Service Card and Japan, and subsequently, the dramatic rise in imported petroleum and exported grain, and the expansion of U.S. trade with the Soviet Union, the Pacific Rim, and the Middle East.

On the shipping side, the relatively small and undifferentiated merchant- men of two generations ago— the war-built Victory and Liberty ships and T-2 tankers—have been all but totally replaced by huge tankers, drybulk carriers, containership car carriers, refrigerated ships, and a bewildering variety of other highly specialized vessel types.

Ships, on average, have become larger, technologically more sophisticated, and significantly more expensive to build and to operate, requiring equally sophisticated ports to turn them around quickly and keep them on schedule. In response, more than $5 billion was invested in commercial port facilities in the United States from 1946 through 1980. During the period 1973-1983, public port authorities alone invested some $3.0 billion in facilities, and are expected to invest another $3.2 billion in capital improvements between 1983 and 1989, according to the Maritime Administration.

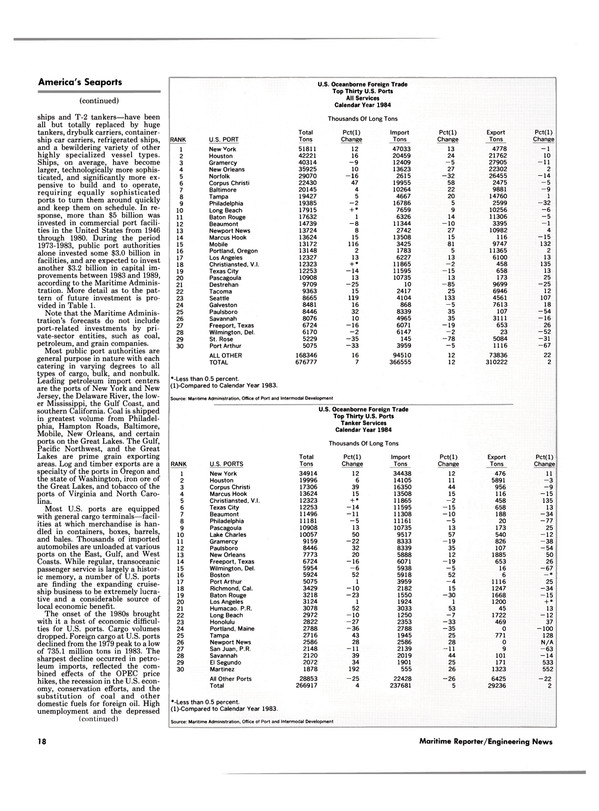

More detail as to the pattern of future investment is provided in Table 1.

Note that the Maritime Administration's forecasts do not include port-related investments by private- sector entities, such as coal, petroleum, and grain companies.

Most public port authorities are general purpose in nature with each catering in varying degrees to all types of cargo, bulk, and nonbulk.

Leading petroleum import centers are the ports of New York and New Jersey, the Delaware River, the lower Mississippi, the Gulf Coast, and southern California. Coal is shipped in greatest volume from Philadelphia, Hampton Roads, Baltimore, Mobile, New Orleans, and certain ports on the Great Lakes. The Gulf, Pacific Northwest, and the Great Lakes are prime grain exporting areas. Log and timber exports are a specialty of the ports in Oregon and the state of Washington, iron ore of the Great Lakes, and tobacco of the ports of Virginia and North Carolina.

Most U.S. ports are equipped with general cargo terminals—facilities at which merchandise is handled in containers, boxes, barrels, and bales. Thousands of imported automobiles are unloaded at various ports on the East, Gulf, and West Coasts. While regular, transoceanic passenger service is largely a historic memory, a number of U.S. ports are finding the expanding cruiseship business to be extremely lucrative and a considerable source of local economic benefit.

The onset of the 1980s brought with it a host of economic difficulties for U.S. ports. Cargo volumes dropped. Foreign cargo at U.S. ports declined from the 1979 peak to a low of 735.1 million tons in 1983. The sharpest decline occurred in petroleum imports, reflected the combined effects of the OPEC price hikes, the recession in the U.S. economy, conservation efforts, and the substitution of coal and other domestic fuels for foreign oil. High unemployment and the depressed state of U.S. industry in general lowered overall demand for goods and services, including those purchased abroad. The soaring value of the U.S. dollar against foreign currency effectively increased the price of U.S. goods and services to foreign purchasers. The worldwide recession made matters worse. Although U.S. coal exports surged in 1980- 1982, that was not enought to cushion the overall drop in trade.

Since 1983, however, there has been a turn around reflecting, in part, the resurgence of the U.S.

economy. In business was good at U.S. ports in 1984, and even better in 1985. Container cargo movements last year reached record highs at many U.S. ports. While petroleum imports and U.S. grain imports remained depressed, the overall picture at U.S. ports is encouraging.

One important factor for U.S. public port authorities has been the continued rise in imported dry cargo, a trend that appears to have continued unabated into the first half of 1986, despite the drop in the dollar.

U.S. coal exports last year hit a near record high of 92.0 million tons; this year promises to be nearly as good, with foreign buyers rushing to take advantage of low prices for U.S.

steam coal. The ongoing OPEC price war appears to have brought a resurgence of U.S. petroleum imports, though volumes are unlikely to ever again reach the peak levels of the 1970s. U.S. grain exports are also expected to recover from last year's dismal performance, reflecting lower U.S. prices engendered by the dollar's fall and the impact of the new farm act. A summary of recent trends in U.S. waterborne imports and exports is provided in Table 2.

Of course, problems remain. The past 10 months have been difficult ones for ports located on the Gulf and Great Lakes, and in the Pacific Northwest. Even though the U.S.

dollar continues to decline, U.S.

trade is still characterized by a heavy imbalance of imports, meaning that ships typically arrive fully laden at U.S. ports and depart empty or partially loaded. Moreover, international shipping is heavily overtonnage in virtually all of the major trades. Stated differently, available shipping capacity is far greater than total available cargo, a problem that will tend to be exacerbated as new buildings enter the market in greater numbers than those removed by scrapping or retirement. Despite the obvious benefits of foreign trade to the U.S.

economy, sentiment persists in Congress and elsewhere for legislation and other governmental actions aimed at curtailing the import of automobiles, steel, lumber products, textiles, and a host of other products.

Federal budgetary problems, particularly those directed at scaling back the enormous national debt, are having their effects on public port management. Examples include reduced manning levels at key federal agencies such as Customs, and limited resource levels for the Coast Guard. In addition, there is an immediate prospect of cost-re- covery, user fee schemes related to a range of federal activities and services all of critical importance to the flow of waterborne commerce.

Agencies involved include the CoTps of Engineers, the Customs Service, the Coast Guard, and the Immigration Naturalization Service. Perhaps most troublesome regarding these user fee schemes is the fact that each user fee scheme has been proposed independently, without an understanding or a recognition of the cumulative impact of all such cost-recovery schemes on the essential flow of U.S. waterborne commerce.

For the past six years, perhaps the most difficult issue for U.S. public port management has been the Reagan Administration's insistence that the traditional federal role in sponsoring most costs involved in new navigation channel construction and channel maintenance must be significantly reduced. After considerable negotiation and debate, the U.S. public port industry has generally accepted the idea that, in return for new channel projects, an increased local nonfederal share of the total project costs will be required.

It should be noted that there has not been an omnibus water projects bill since 1970—nearly 16 years!

Moreover, the public port industry has acknowledged the inevitability of a system of user fees established to recover a portion of the Corps maintenance costs. This radical new port development legislation may be enacted by the time this article is published. Clearly, one potential advantage of increased local cost-sharing for federal navigation channel projects is the prospect of greatly speeding up the process by which those projects are approved, funded, and constructed which now takes, on average, more than 25 years.

In spite of these increased cost burdens proposed to be placed on U.S. public port authorities at the federal level, the Reagan Administration and certain members of Congress had proposed, within the rationale of "tax-reform", legislation that would have virtually eliminated the ability of public port authorities to use tax-exempt bonds to finance port facility development.

Wisely, both houses of Congress have recognized the fundamental importance of continuing the taxexempt bond financing capabilities of public ports in tax-reform legislation that is (as of this writing) now in Senate/House Conference Committee.

Certain restrictions still need to be resolved, but the basic public purpose of public port authorities to develop facilities needed to serve the essential flow of U.S.

waterborne commerce has again been confirmed by the U.S. Congress.

In short, the outlook for the U.S.

public port industry is positive. U.S.

public port authorities continue to demonstrate their ability to fulfill their critical responsibilities in promoting the interests of their local communities, their region, and the nation.

Read AMERICA'S SEAPORTS The Dynamics Of Change in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of August 1986 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from August 1986 issue

Content

- MacGregor-Navire Announces Key Appointments page: 4

- New Repair Yard Under Construction In Southern Chile For ASMAR & Partner page: 6

- Yamazaki New President Of Sumitomo Machinery page: 6

- Auxiliary Rescue Salvage Vessel Commissioned At Peterson Shipyard page: 7

- NOR-FISHING '86 Trondheim, Norway, August 11-16 page: 8

- McDermott Shipyard Lays Dredge Keel page: 10

- Valmet Testing Newly Developed Ducted Propeller For Icegoing Vessels page: 10

- Wiismuller Salvage And Offshore Tugs Inc. Form New Company page: 11

- Bethlehem's Sabine Yard Busy With Drill Rig And Ship Dockings page: 12

- Fleet Oiler Construction At Penn Ship Adds To Beginning Of A New Era page: 12

- Cummins Diesels Selected To Repower Research Vessel Calypso page: 14

- Nichols Brothers Yard Delivers Luxury Catamaran Cruise Vessel page: 14

- AMERICA'S SEAPORTS The Dynamics Of Change page: 16

- AAPA's 1986 Annual Convention Set For Miami page: 22

- New Intertanko Publication— 'TANKER PORT PARTICULARS 1986' page: 25

- Ameroid DC Disc Cleaner Approved For Cleaning Westfalia Disc Stacks page: 25

- Bollinger Named Chairman Of Louisiana Shipbuilding And Repair Association page: 27

- Navy Selects Ingalls For Planning Reactivation Of Battleship Wisconsin page: 27

- Newport News Shipbuilding And SNAME Sponsor Ship Production Symposium page: 28

- M.A.N.-B&W Offers Cost-Saving Systems For Their MC Engines —New Brochures Available page: 29

- Honeywell Marine Systems Division Restructures Marketing Organization page: 30

- Free Eight-Page Brochure On Marine Powermeters Offered By Acurex page: 31

- ONS '86 SHOW AND CONFERENCE ATTRACTING STRONG INTEREST FROM EXHIBITORS page: 32

- Daewoo-Built Vehicle Carriers To Have MacGregor-Navire Access Equipment page: 35

- Fairbanks Morse Engine Division Ships First Colt-Pielstick PC4.2 page: 36

- Stable Offshore Platforms Planned By Navy For Aircraft Training Exercises page: 36

- Gear Rating Discussed At Joint Meeting Of ASNE And SNAME Sections page: 36

- New Fuel Consumption Monitoring System From Kockumation page: 36

- Tacoma Boat Launches Ocean Surveillance Ship For Navy's MSC page: 37

- Baldt Marks 85th Year As Major Supplier To Marine/Offshore Industries page: 37

- Workboats Northwest Yard Delivers High-Speed Fireboat To Ketchikan page: 38

- SI Introduces 'First Family' Of Survival/Exposure Suits page: 38

- Tidewater Marine Upgrades Another Towing/Supply Vessel At McDermott page: 39

- Magnus Maritec Named Exclusive Marine Supplier Of Ethysorb products page: 40

- Marinette Marine Launches First In Yard Patrol Boat Series page: 40

- Captain Wages Joins MSI As Director Of New Simulator Training Center page: 40

- Newfoundland-Sweden New Joint Venture Company page: 40

- Ward Leonard Electric Offers Free 10-Page Push Button Catalog page: 41

- Hydrostatic Drives Propel Many New 'Old-Time' Paddlewheelers page: 42

- Hyster Expands XL Line Of Lift Trucks page: 45

- Conrad Shipyard Delivers Unique Drydock To Republic Of Venezuela page: 45

- Shipmate's RS-6100 Navtex Receiver page: 49

- Offshore Production And Test Ship Delivered By NKK To Norwegian Owner page: 49

- Microprocessor-Based System Monitors/Controls Mooring Lines page: 50

- Moss Point Marine Completes Tug For Panama Canal Commission page: 50

- New 12-page Catalog On Multi-Port Ball Valves Offered By Pittsburgh Brass page: 50

- Bay Shipbuilding Progressing With Construction Of Sea-Land Containerships page: 55

- Moss Point Marine To Build Multipurpose Boat For U.S. Agency page: 55