Sideways to Swimmers: Unusual Tank Testing

Offshore supply vessels, passenger vessels, yachts. How much power is required and how will they ride in seas?

These are the questions Gerry Stensgaard, P.Eng, and the staff at the Ocean Engineering Centre (OEC) of Vizon Scitec (formerly BC Research) usually answer. But over the years naval architects and others have asked for answers to some unusual questions.

"They are open minded about special testing," says Tim Nolan. P.E., Naval Architect at Tim Nolan Marine Design, PC.

Special testing might mean a peculiar test of a typical craft. Or it might be basic resistance and seakeeping tests for an unusual craft; which might seem easy, but the test setup can become difficult.

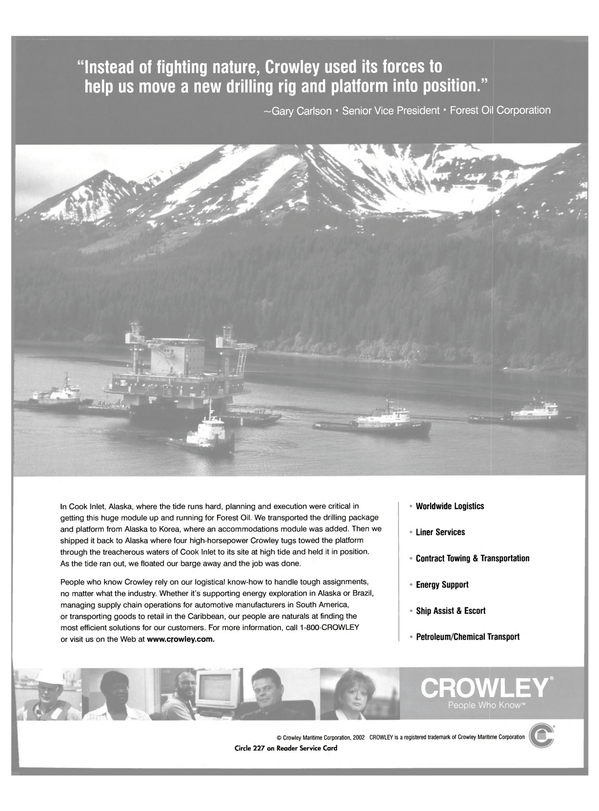

"We are solution oriented," says Stensgaard, "If someone has a problem, we try and come up with a setup that will give the answers." Located in Vancouver, Canada, the OEC consists of a 220 by 12 ft. wide towing tank, whose carriage has a maximum speed of 19.7 ft./sec. Though most of the testing takes place in this tank, there is also an 8,700 sq. ft. wave basin with wavemakers. It is one of the few commercial towing tanks in North America.

A good example of unusual testing was for the new 50 x 22 ft. cable ferries replacing the 50 x 18 ft. ones already operating on the Missouri River in three locations near Great Falls, Montana.

Each ferry is attached to two cables across the river. One is the overhead trolley cable, which keeps the ferry from being carried downstream, and the other is the power cable, which pulls the ferry across the river. As Mike Complita.

P.E., Project Engineer at Elliot Bay Design Group (EBDG) explains, "we needed to understand the load put on the cable system at all river flows. The only design literature we could find, remotely similar, was on offshore mooring systems.

But the numbers we were getting for cable size were way too large compared to what's been in operation for 100 years." To answer their questions they wanted to tow the models of the old and new ferries sideways to simulate the river current. Stensgaard reports towing the models sideways as opposed to lengthwise wasn't easy, "there was a suction force on the upstream side of the model, which with the normal testing setup, was pulling it under water. In real life the overhead cable prevents that, so we had to model them with load cells on wires to measure resistance." Another peculiar test involved pulling a model of the Puget Sound Pilot Boat beside a sheet of plywood. The boat is a 74 x 19 ft. waterjet propelled craft operating out of Port Angeles, Wash.

According to Ed Hagemann. P.E., of Hage-Marine, Inc. (which collaborated on the design with Tim Nolan Marine Design), "We wanted to have a level boat, that is with zero roll attitude when along side, because the whole purpose of the pilot boat is to come along side a ship safely. The test set up duplicated the forces and moments from the waterjet and though not an exact representation, the plywood simulates the circumstance of being along side. The tow tank promised a boat that wouldn't roll and that's how it turned out. In fact, the transfer speed went from 8 knots with the old boat to 12 knots with ours." Sometimes the answer the tank gives is not the one the naval architects want to hear. The M/V Empress of the North, is a Guido Perla & Associates, Inc (GPA) designed 360 ft., 235-passenger, coastal paddlewheel vessel for use in Alaska; which means it sees open water, not standard fare for what is typically a river boat design. As such, GPA did seakeeping tests on the hull design. "We flunked the first time," admits Dave Pasciuti, P.E., Vice President at GPA "With the open deck structure we found we had some real problems. We had to modify the hull shape in the main deck area to make it more ocean-going-like." Another example shows that testing can be used in retrofit situations and, even with computer modelling now readily available, tank testing is still needed. EBDG was asked to improve the performance of the Spirit of Endeavour, a 217 ft. x 37 ft. small cruise ship. They suggested three options: a stern extension, a bulbous bow. or both.

Testing was done on the base hull, each improvement separately, and in combination.

From the tests, "it was surprising how much the stern extension improved performance," says Doug Wolfe, P.E., Vice President at EBDG.

The bulb selection and testing was interesting in itself. According to Stensgaard, "Elliot Bay wanted to try a new bulb optimization computer program just out of academia. So they had an 'optimum' bulb designed for retrofitting onto this vessel. Then we checked the resistance in our tank and found the bulb successfully increased the resistance by over 10%. So we went to work to change the shape of the bulb based on our previous testing experience and managed to reduce the resistance to below the baseline." Compared to other tanks around the world, the OEC is on the small side. "It can't do large stuff or manouevering," says Wolfe. Pasciuti adds, "It's too small to do self propelled tests." Stensgaard admits, "if nothing else we're honest. We'll tell somebody when we're not appropriate. I think as a result, many of our customers are repeat customers." And even though they can't do direct quantitative tests of larger vessels, Stensgaard points out, "we can still quickly do comparative and qualitative tests." He cites water-on-deck studies for both BC Ferries and Alaska State Ferries as examples.

Boats and ships aren't the only things the OEC has tested. "We've tested fishing nets, log booms, seaplane floats, hovercraft, SWATHs, articulated tugbarges, even a planing armoured personnel carrier," reports Stensgaard. In fact by attaching a full scale mannequin to the towing carriage, Aerosports Research, an aero/hydrodynamic consultancy that works with Nike, has used the towing tank to test the drag of swim suits. According to Len Brownlie, President of Aerosports Research, "we've found different fabrics have as much as a 6% difference in drag between the best and worst, even for the same fit and cut." Brownlie likes the tank because compared to other facilities like swimming flumes, "it offers precise velocity control and excellent repeatability on drag measurements." Hagemann summarizes the facility, "even though it's a fairly straightforward tank, that makes it affordable. So with ingenuity and forethought one can design a test off the beaten path and walk away having learned something or verified something." Circle 63 on Reader Service Card

Read Sideways to Swimmers: Unusual Tank Testing in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of September 2004 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from September 2004 issue

Content

- SSI Concerns Continue page: 5

- Signed Confessions page: 9

- OMI to Pay $4.2M for Waste Oil Dumping page: 14

- NASSCO Delivers Alaskan Frontier page: 17

- Alabama Shipyard to Build Hopper Dredge page: 17

- Merwede Tapped for Navy, Commercial Contracts page: 18

- FBM Babcock Wins U.S. Contract page: 19

- New Vessels from VT Halmatic page: 19

- ABCO Launches Three New Boats page: 20

- IR Generates $64M in Orders page: 24

- Sideways to Swimmers: Unusual Tank Testing page: 26

- Current Uses of FEA in Shipbuilding page: 30

- BMT Aims to Improve Vessel Evac page: 32

- Flensburg Makes its Mark Again page: 36

- SMM 2004: Ready for the World page: 36

- German Shipyards Propose Merger page: 37

- Voith to Exhibit VWT Baut at SIMM page: 37

- Blohm + Voss Repair Wins Business page: 38

- Methane Arctic Benefits from German Technology page: 39

- Becker Kort Rudder Nozzles for Improved Maneuverability page: 40

- Payer Presented Cross of the Order of Merit page: 42

- Xantic: Focus on Integrated Solutions page: 44

- A Benchmark in Electronic Fuel Injection page: 45

- Q&A with Wartsila CTO Matti Kleimola page: 46

- Seacor Crewboats "Eliminators" Some Maintenance Costs page: 49

- (Fuel) Cells of Endeavor page: 50

- Containerships: When Will One Engine Not Be Enough? page: 52

- Most Powerful Common- Rail Engine Passes Test page: 54

- Clean Concept for Brostrom Tankers page: 54

- Canadian Towing Firm Refits for the Future page: 56

- TOR: The Next-Generation Turbocharger page: 57

- Duramax Marine Creates Largest Ever DuraCooler page: 58

- ABS: Large Ship Hull Deflections Impact the Shaft Alignment page: 60

- The Great Maritime Disruption... that Never Happened page: 66

- New Positioning Technique Helps Cut Costs in Deepwater GOM page: 76

- U.S. Ferry Market Prospects Looking Up page: 77

- "Ship Design and Construction" page: 81