Page 70: of Maritime Reporter Magazine (June 2011)

Feature: Annual World Yearbook

Read this page in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of June 2011 Maritime Reporter Magazine

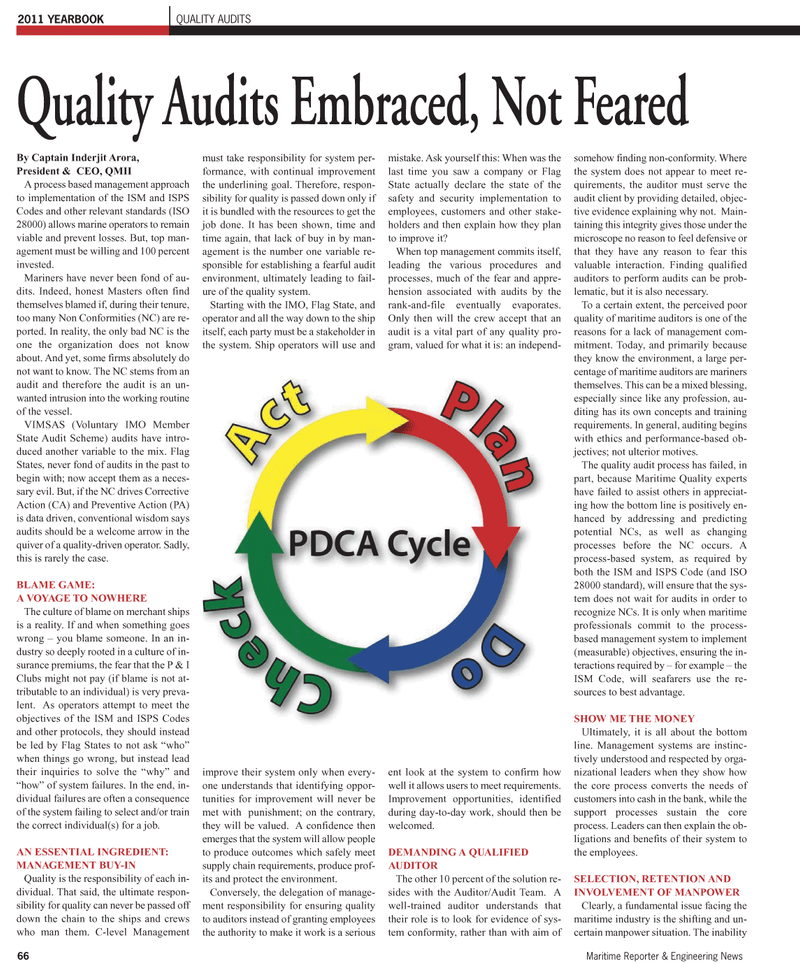

66Maritime Reporter & Engineering News By Captain Inderjit Arora, President & CEO, QMII A process based management approachto implementation of the ISM and ISPSCodes and other relevant standards (ISO 28000) allows marine operators to remain viable and prevent losses. But, top man- agement must be willing and 100 percentinvested. Mariners have never been fond of au- dits. Indeed, honest Masters often find themselves blamed if, during their tenure, too many Non Conformities (NC) are re- ported. In reality, the only bad NC is the one the organization does not know about. And yet, some firms absolutely do not want to know. The NC stems from an audit and therefore the audit is an un-wanted intrusion into the working routine of the vessel. VIMSAS (Voluntary IMO Member State Audit Scheme) audits have intro- duced another variable to the mix. Flag States, never fond of audits in the past to begin with; now accept them as a neces- sary evil. But, if the NC drives Corrective Action (CA) and Preventive Action (PA) is data driven, conventional wisdom says audits should be a welcome arrow in the quiver of a quality-driven operator. Sadly, this is rarely the case. BLAME GAME: A VOYAGE TO NOWHERE The culture of blame on merchant shipsis a reality. If and when something goes wrong ? you blame someone. In an in-dustry so deeply rooted in a culture of in-surance premiums, the fear that the P & IClubs might not pay (if blame is not at-tributable to an individual) is very preva- lent. As operators attempt to meet the objectives of the ISM and ISPS Codes and other protocols, they should instead be led by Flag States to not ask who?when things go wrong, but instead lead their inquiries to solve the why? and how? of system failures. In the end, in- dividual failures are often a consequence of the system failing to select and/or train the correct individual(s) for a job. AN ESSENTIAL INGREDIENT: MANAGEMENT BUY-IN Quality is the responsibility of each in-dividual. That said, the ultimate respon- sibility for quality can never be passed off down the chain to the ships and crews who man them. C-level Management must take responsibility for system per- formance, with continual improvement the underlining goal. Therefore, respon- sibility for quality is passed down only if it is bundled with the resources to get the job done. It has been shown, time and time again, that lack of buy in by man- agement is the number one variable re- sponsible for establishing a fearful auditenvironment, ultimately leading to fail- ure of the quality system.Starting with the IMO, Flag State, andoperator and all the way down to the ship itself, each party must be a stakeholder in the system. Ship operators will use andimprove their system only when every- one understands that identifying oppor- tunities for improvement will never be met with punishment; on the contrary, they will be valued. A confidence then emerges that the system will allow people to produce outcomes which safely meetsupply chain requirements, produce prof-its and protect the environment. Conversely, the delegation of manage- ment responsibility for ensuring qualityto auditors instead of granting employees the authority to make it work is a serious mistake. Ask yourself this: When was the last time you saw a company or Flag State actually declare the state of thesafety and security implementation toemployees, customers and other stake- holders and then explain how they plan to improve it? When top management commits itself,leading the various procedures and processes, much of the fear and appre-hension associated with audits by therank-and-file eventually evaporates. Only then will the crew accept that an audit is a vital part of any quality pro- gram, valued for what it is: an independ- ent look at the system to confirm how well it allows users to meet requirements. Improvement opportunities, identified during day-to-day work, should then be welcomed.DEMANDING A QUALIFIED AUDITOR The other 10 percent of the solution re-sides with the Auditor/Audit Team. A well-trained auditor understands thattheir role is to look for evidence of sys- tem conformity, rather than with aim of somehow finding non-conformity. Where the system does not appear to meet re-quirements, the auditor must serve the audit client by providing detailed, objec- tive evidence explaining why not. Main- taining this integrity gives those under the microscope no reason to feel defensive or that they have any reason to fear this valuable interaction. Finding qualified auditors to perform audits can be prob-lematic, but it is also necessary. To a certain extent, the perceived poor quality of maritime auditors is one of the reasons for a lack of management com-mitment. Today, and primarily because they know the environment, a large per- centage of maritime auditors are marinersthemselves. This can be a mixed blessing, especially since like any profession, au- diting has its own concepts and training requirements. In general, auditing begins with ethics and performance-based ob-jectives; not ulterior motives. The quality audit process has failed, in part, because Maritime Quality experts have failed to assist others in appreciat- ing how the bottom line is positively en- hanced by addressing and predictingpotential NCs, as well as changingprocesses before the NC occurs. A process-based system, as required byboth the ISM and ISPS Code (and ISO28000 standard), will ensure that the sys-tem does not wait for audits in order to recognize NCs. It is only when maritimeprofessionals commit to the process-based management system to implement(measurable) objectives, ensuring the in- teractions required by ? for example ? the ISM Code, will seafarers use the re- sources to best advantage. SHOW ME THE MONEY Ultimately, it is all about the bottom line. Management systems are instinc-tively understood and respected by orga- nizational leaders when they show how the core process converts the needs of customers into cash in the bank, while thesupport processes sustain the coreprocess. Leaders can then explain the ob- ligations and benefits of their system to the employees. SELECTION, RETENTION AND INVOLVEMENT OF MANPOWER Clearly, a fundamental issue facing the maritime industry is the shifting and un-certain manpower situation. The inability 2011 YEARBOOKQUALITY AUDITSQuality Audits Embraced, Not Feared

69

69

71

71