Rerouting a River

The Old River Control Structure and its future implications for the Mighty Mississippi

Prior to about 1500, the bodies of water now called the Mississippi River and the Red River (also known as the Red River of the South) were roughly parallel along their southern reaches, each emptying separately into the Gulf of Mexico. About 1500, the Mississippi, which has a long history of meandering, developed a large bend to the west in the vicinity of what is now Point Breeze, Louisiana. That bend, sometimes referred to as Turnbull’s Bend, connected with the Red River and had the effect of making the Red River basically a tributary of the Mississippi, with only a small portion of its waterflow continuing south. That southern waterflow is now called the Atchafalaya River.

Everything was fine until 1831, because the water basins in that region shifted regularly about every 1,000 years. The land and its occupants, including humans, adjusted. The early 1800s saw the rise of the steamboat era. Time became paramount. Turnbull’s Bend was a 20-mile detour that only moved the steamboat two miles further as the crow flies. This was unacceptable.

Henry Shreve, a steamboat captain and owner, inventor, and engineer, had developed technology to clear snags and obstructions from the river. In 1831, he dug a shortcut across the narrowest portion of Turnbull’s Bend, shortening the Mississippi by over 17 miles. The meander lost most of its waterflow and became known as the Old River and carried a relatively small amount of water between the Mississippi and the Red/Atchafalaya River. When the Mississippi was high, the Old River flowed west. When the Mississippi was low, the Old River flowed east. The majority of the time, the Mississippi was higher than the Red/Atchafalaya River.

Initially, the total waterflow through the Atchafalaya was about 10% of that through the Mississippi, but over time this varied to as high as 30%. Since the length of the Atchafalaya was noticeably less than the length of the Mississippi from Point Breese to the Gulf and since the Mississippi continued to meander, there was concern that the Mississippi might eventually change course and flow through the Atchafalaya. This would have the effect of largely cutting Baton Rouge and New Orleans off from the significant waterflow, devastating their economies.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) was called upon to resolve the potential problem. In 1963, it completed construction of the Old River Control Structure at Point Breeze. The structure’s mission was to maintain the status quo, keeping the waterflow of the Atchafalaya at 30% that of the Mississippi. This was accomplished by means of the Low Sill Control Structure for regulation of routine waterflow through operation of a dam and outflow channel and the Overbank Control Structure for supplemental waterflow control when the Mississippi floods. A navigation channel and lock were also included, allowing tugs and barges to transit between to two river systems.

A major flood in 1973 severely tested the Control Structure and nearly caused its complete failure. Flood waters scoured a 55-foot hole under the south end of the Low Sill Control Structure and part of it collapsed into the waterway. It took the emergency dumping of 250 thousand tons of rock into the waterway to save the structure.

An Auxiliary Structure was added in 1986 to reduce pressure on the original floodgates and a hydroelectric facility was added in 1990. The hydroelectric facility takes advantage of the difference in water levels between the two rivers to generate electricity and has largely eliminated the need for water to flow through the Low Sill Control Structure during normal conditions.

The problem with the hydroelectric facility is that it only removes water from the Mississippi. The silt is filtered and largely prevented from entering the Atchafalaya. As a result, the ever-present silt remains in the Big Muddy and is distributed through a smaller volume of water, while a noticeable amount of the clean water has been sent to the Atchafalaya River. The additional clear water leads to increased scouring of the Atchafalaya River basin. The now siltier Mississippi has a difficult time keeping all that silt in suspension. Much of it descends to the bottom. As the river bottom comes up, so must the water level at the surface. This has the effect of requiring levees along the river to be raised. It also has the effect of increasing the pressure on the Old River Control Structure. The increased silt deposit is also a reason that dredging of the river in constantly taking place.

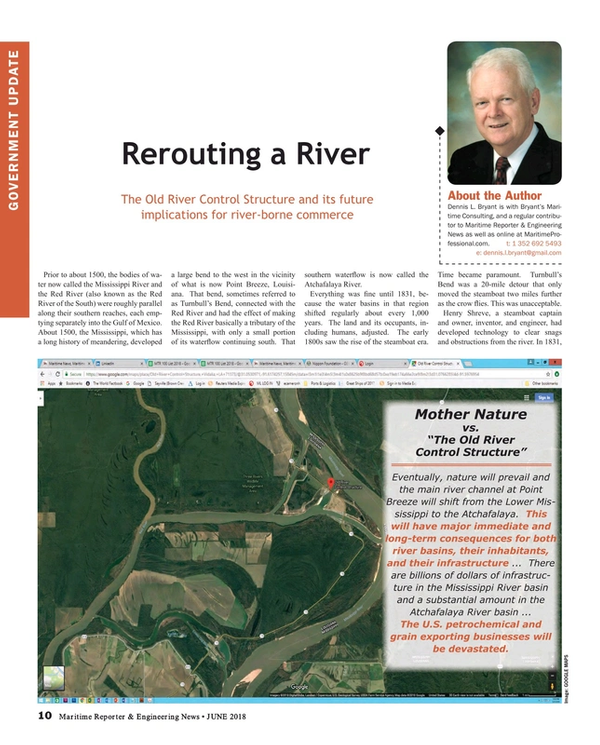

Eventually, nature will prevail and the main river channel at Point Breeze will shift from the Lower Mississippi to the Atchafalaya. This will have major immediate and long-term consequences for both river basins, their inhabitants, and their infrastructure. Millions live within the Mississippi River basin south of Point Breeze. Another million live in the Atchafalaya River basin. There are billions of dollars of infrastructure in the Mississippi River basin and a substantial amount in the Atchafalaya River basin. In addition, those living and working in the Mississippi River basin depend on the river with its significant water flow to prevent salt water intrusion into the water table. The U.S. petro-chemical and grain exporting businesses will be devastated.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers declines to say when this change in the water flow will occur, but does not argue with the proposition that it is inevitable. The Corps does say that it will continue to operate the Old River Control Structure, holding back the Mississippi’s predilection to move west, so long as Congress continues to appropriate the necessary funds to maintain and upgrade the structure. There will come a point, though, when Plan B must be considered.

The Mississippi River and its Old River Control Structure are vital parts of our national infrastructure. Close attention to their situation is of national importance.

Read Rerouting a River in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of June 2018 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from June 2018 issue

Content

- Rerouting a River page: 10

- Nippon Foundation Addresses Global Ocean Threats page: 18

- Odin's Eye & the Quiet Trawler page: 28

- Maritime Decarbonization: The Path Starts in Norway page: 32

- Cruise Ship Construction: China Rising page: 41