Ship Design & The Inevitability of Change

At one time the most powerful lighthouse in the United States was Twin Lights in Highlands New Jersey. Today it is a wonderful little museum and right now it has a very interesting show of paintings by Maarten Platje on the War of 1812. One painting is called the Great Chase and it tells this amazing story of the US Frigate Constitution being becalmed off the New Jersey coast and becoming engaged in a rowing race to keep out of range of a powerful British Squadron. The Constitution escaped and went on to have her amazing victories that year, but if she had been caught, today we would have never heard of her.

What really struck me as interesting is that, while this rowing race was taking place offshore, Robert Fulton was running his steamboat up and down the Hudson not even 100 miles away. If that steamboat had been out there to tow the Constitution, she could have outmaneuvered the entire squadron and really put a hurt on the British, and navy steam would have been adopted overnight.

Instead, we know that steam did not become a feature of naval warfare until the Civil War half a century later.

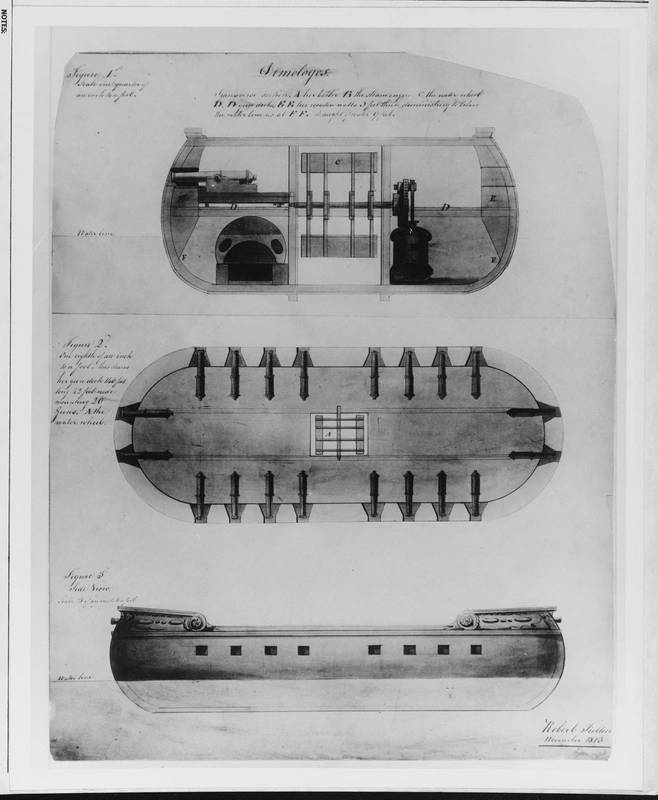

What is less well known is that during the War of 1812 Robert Fulton built a steam gunboat and even delivered it to the US Navy, but the Navy never quite figured out what to do with it.

Why did it take so long for the technology to be accepted? There are too many reasons for this column to discuss that, but in this 80th anniversary issue of Marine Reporter you are probably reading about things that may appear strange today, but will be commonplace in the 100th anniversary issue. (Maybe I will still write an occasional column at that time and can check back how wrong I was today.)

Steam Battery "Demologos" (1814) Drawing by her designer, Robert Fulton, November 1813, showing the ship's general arrangement. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

Steam Battery "Demologos" (1814) Drawing by her designer, Robert Fulton, November 1813, showing the ship's general arrangement. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

As far as predicting the future is concerned, I am not interested in things that are simply the march of technology like ship autonomy. For my prediction I am reaching back to that painting. I am betting that, in 20 years, commercial sail will have found a new footing in commercial maritime.

I don’t think that sail will become a dominant means of propulsion, but with the pressures of carbon reduction, and a combination of parallel innovations, I am starting to think that there will be a place for commercial sail in long haul bulk transportation.

I see quite a lot of sail propulsion proposals out there and, on a technological level, some proposals make sense to me, and others make no sense at all, but what I rarely see is a system analysis of the use of sail in bulk transportation.

The combination of incredibly improved communication methods, vastly better weather and current predictions, and emerging sail technologies, inherently will make sail propulsion much more reliable and will vastly improve the transit times between distant ports over the early 20th century transit times.

The improvement is not just marginal; it is momentous. While I am not for a second suggesting that sailing bulkers will go as fast as today’s fastest sailboats, it should never be forgotten that the fastest waterborne circumnavigations have been achieved with sailboats. Not steamships, not diesel ships, not nuclear ships, not even nuclear submarines; the fastest waterborne circumnavigation was accomplished by the trimaran IDEC 3 in 2017 at 41 days. This boat’s inherent top speed of 33 knots (that is average speed over 24 hours!) was needed, but speed means nothing if you can’t keep the wind, and weather routing allowed this record to be set.

Unfortunately, it is mathematically more difficult to take advantage of weather routing if your vessel is slower (it is more difficult to route the vessel into the optimal winds and to keep it there), but longer term accurate predictions and big oceans with lots of alternatives help a lot.

Today it is not unrealistic to assume an average transit speed of 8-10 knots on long voyages for big sailing bulkers.

That is zero emissions at speeds that are not far away from slow steaming bulkers!

Unfortunately, the logistics customer today wants predictability and average speeds are not the same as actual speeds, and therefore the cargo may arrive a little late, or a little early.

There are two ways to fix this issue. One is to generate a little energy underway with solar or trailing propeller systems. This energy can be managed to keep the vessel in the wind zones by running under power for relatively short distances when needed.

The other way to fix it is to think in logistical system terms. If we think of sailing bulkers as both transport and storage devises, a fleet of sailing bulkers can simply be loaded and sent on their way to deliver the cargo at some distant location. Once the flow starts, the vessels can be scheduled to arrive earlier and simply keep station under sail until the berth is available. Two or three vessels in the proverbial pipeline can ensure, to a very high degree of certainty, that cargo will be delivered when required.

Most likely sailing bulkers will use a combination of both approaches and other technological advances that will come down the pike in the next few decades.

I am pretty sure it will happen, unless there is a renewed interest in nuclear propulsion. Newer nuclear technologies show a huge amount of promise, but while an individual shipowner can elect to invest in sail, the investment in nuclear needs to be driven by government investment. And government investment in maritime is as rare as a young nation with a small Navy being able to teach the largest Navy in the world a lesson or two.

The Author

Rik van Hemmen is the President of Martin & Ottaway, a marine consulting firm that specializes in the resolution of technical, operational and financial issues in maritime. By training he is an Aerospace and Ocean engineer and has spent the majority of his career in engineering design and forensic engineering.

This article was first published in the October 2019 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News. For each column I write, Maritime Reporter & Engineering News has agreed to make a small donation to an organization of my choice. For this column I nominate Twin Lights Historical Society, the co-organizer (with NMHA) of Guns Blazing! The War of 1812 exhibit at Twin Lights Museum in Highlands, NJ. The show will run through November 22, 2019. http://www.twinlightslighthouse.com/about-us.html

Read Ship Design & The Inevitability of Change in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of October 2019 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from October 2019 issue

Content

- Containership Fires page: 16

- Interview: Nigel Shewring R&D Director, Hempel page: 24

- Maritime History & the Panama Canal page: 26

- C-Job CEO Basjan Faber was Born to Design page: 34

- Gibbs & Cox: Historic Ship Designer Turns 90 page: 40

- Ship Design & The Inevitability of Change page: 46

- Ship Design: Evolving for Efficiency, Compliance page: 50

- Robert Allan Ltd.: The Evolution of Marine Design page: 52

- Interview: Cory Wood, VP, Bristol Harbor Group page: 54

- Maritime 2050: Facing the Decarbonization Challenge page: 58

- ABS & the Future of Classification page: 60