For Ship Recycling, Grieg (Goes) Green

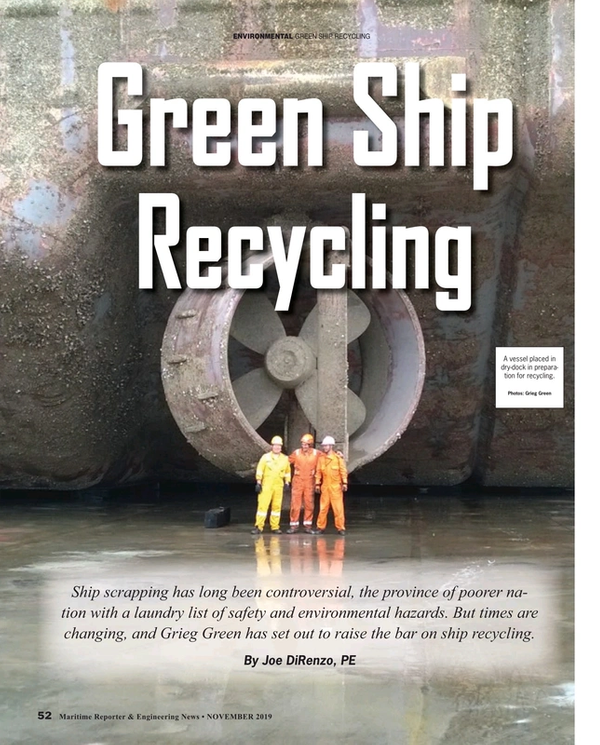

In May 2014 National Geographic wrote an in-depth article on shipbreaking operations in Bangladesh where they listed shipbreaking as one of the deadliest professions in the world. The images from these shipyards are well circulated among professionals in the shipping industry. Individuals without personal protective equipment cutting and grinding into a ship that was haphazardly beached and torn asunder by unskilled laborers.

Pollution swirl in the nearby tidal area and soot belches into the air. Large sections of ships come careening off endless rows of vessels that litter the beach.

Shipping companies that have erred in selling their ships to unsavory cash buyers have felt the consequences to their reputation and income sheets. One of the recent main headlines includes the Harrier case, formerly Eide Carrier, in Norway in which a scurrilous cash buyer attempted to circumvent EU waste management laws to send the vessel to a scrapping yard in Pakistan. Similarly, in March 2018, shipping company Seatrader was fined in a Dutch court for using substandard shipbreaking facilities in Southern Asia to recycle their vessels.

As a result of these stand-out headlines, there is tremendous pressure from both government regulators and within the shipping industry to change the status quo when it comes to ship recycling. This pressure has created an interesting market space for ship recycling consultancies that will assist shipowners in managing the ship recycling process and ensure that they are being conducted in accordance with international regulations and industry best practices. One such company involved in this field of work is Grieg Green whose main office is located in Oslo, Norway.

Mrs. Elin Saltkjel, Head of Quality Assurance and Business Development at Grieg Green offered insight into changing dynamics within the ship recycling industry and growing trends. Specifically, she explains how ship recycling consultancies like Grieg Green allow ship owners to hedge risk against ship recycling projects which may result in damage to the reputation or their bottom line. Current events have shown that this risk may exist even after ship owners have sold the vessel to a cash buyer and no longer owns it. This article explores how the development of this interesting business model could eventually lead to the shipbreaking operations around the world becoming more humane and sustainable.

The Wrong Way to Recycle A Vessels

To place pressure on both shipowners and government regulations, a number of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) have sprung up to help “clean up the business” of ship recycling. One such NGO called “NGO Shipbreaking Platform” outlines how a network of unscrupulous shipowners, cash buyers, shipping insurance companies, and shipbreaking facilities have, in the past, circumvented international laws and regulations.

Critical to the ship recycling transaction (honest or otherwise) is the “cash buyer”. According to NGO Shipbreaking Platform, a cash buyer is essentially a middleman who “pay[s] ship owners up-front before the ship reaches its final destination to be dismantled, and then re-sell[s] the ship to the breaker that can offer the highest price, thereby making a profit with the price different”. In cases where shipowners have been held accountable for this practice, an often-used excuse is that the shipowner was unaware that the vessel would eventually end up at these notoriously dangerous and pollutive shipyards. Recent court rulings, such as the Harrier case, have indicated that this lack of awareness does not indemnify the ship owner of liability if the ship is recycled in an improper manner. Once purchased by a cash buyer, the new owner will use a number of different tactics to skirt international maritime ship recycling regulations such as shifting to a flag of convenience. According to NGO Shipbreaking Platform, “an end-of-life sale with the help of a cash buyer usually includes a change of flag to one of the typical last voyage flags, and the registration of the vessel under a new name and a new post-box company”. Unfortunately, dishonest cash buyers will ultimately choose shipyards with associated downstream recycling operations that maximize their profit regardless of how much human suffering and environmental damage is caused in the process.

Ship Recycling Conventions and Regulations

Although not exhaustive, the Basel Convention, Hong Kong Convention and EU Ship Recycling Regulations form the crux of current ship legal framework in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). According to Norwegian based maritime legal firm Tommessen AS in a primer called “Scrapping of Ships: Is beaching illegal?”, the Basel Convention, created in 1992, “forbids transportation of hazardous waste to countries that have not ratified the Convention, and transportation of hazardous waste between member states when the recipient country cannot deal with the waste in line with the Convention”. The convention treats ships which have reached the end of their lifecycle as “hazardous waste” because they may contain hazardous substances like “asbestos, lead, and PBC”. In practice, the Basel Convention is implemented in the EU/EEA countries through the Waste Regulation and Cross-Border Regulation.

In order to create a set of regulations that specifically targets the practice of ship recycling, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the International Convention regarding Safe and Environmental Recycling of Ships, known in the shipping industry as the “Hong Kong Convention” (HKC). Although not ratified by the requisite number of countries representing 40% of global shipping by gross tonnage, the EU has implemented the convention through the EU Ship Scrapping Regulation (SSR) (Regulation 2013/1257). As of 2018, these regulations have entered into force for all European flagged vessels. Additionally, by the end of 2020, a number of facets of these regulations will be applicable for non-EU flagged vessels which call on European ports or anchor off the European coast.

Most notable of these regulations is the requirement for all vessels to carry an Inventory of Hazardous Material (IHM) which is an active list of all hazardous material carried on the vessel. According to the IMO’s website, “ships will be required to have an initial survey to verify the inventory of hazardous materials, additional surveys during the life of the ship, and a final survey prior to recycling”.

When it comes time to recycle a vessel, the IHM is a critical living document used by both by the shipyard and ship recycling experts like Grieg Green to verify that all hazardous material is removed and disposed of in an appropriate manner. Another important outcome of the HKC and SSR is the need for the vessel to be recycled at an EU approved ship recycling facility with a class certified Ship Recycling Facility Plan (SRFP). Finally, before the recycling process begins each vessel is required to have a Ship Recycling Plan (SRP) which has been uniquely tailored to the vessel.

The Right Way to Recycle A Vessel

Given the recent international pressure on shipowners to change past practices, many shipping companies are turning to ship recycling consulting experts like Grieg Green to conduct the IHM survey and oversee the ship recycling process. Mrs. Saltkjel indicated that Grieg Green acts as an agent of the shipowner and will oversee either parts of the ship recycling process, like the actual shipbreaking activities at an approved yard, or through the entire process which includes the contract negotiations with buyer, export/ import applications and delivery.

When asked about how Grieg Green’s functions differ from class societies, Mrs. Saltkjel stated, “We are careful not to use the words ‘certifying’ or ‘validating’. We have our own checklist based on the Hong Kong Convention and the EU SSR. We always start with an initial visit where we walk around the facility, talk to [the management and workers at the Ship Recycling Facility] and look at their documentation to get an impression of their adherence to the regulations and how well they understand them. It is important to get the feel for the management….Is this really a commitment from their side [to comply with the Hong Kong and EU SRR regulations] or more like ‘hey, can you approve this so we can get more business’”?

One of the unfortunate realities Mrs. Saltkjel points out is that sometimes class societies will validate that the SRFP meets the guidelines stated in the HKC and SSR but either the shipyard surges resources during the inspection to appear as though they are compliant or they comply but choose not to follow the regulations when they are not being externally monitored.

“The problem is that the follow up of the adherence to the rules is [for example] two years in between. [Class societies] come just for a few days to inspect …Many yards have Hong Kong convention compliance certificates, but the yards are not following the rules between the inspections. Unless the local authorities take some ownership for it and they make their own follow up which is what the EU expects from their member states then you cannot be sure when you go to one of these facilities that it will not be polluting”.

In order to protect the reputations of shipowners, Grieg Green is selective about which yards and cash buyers they recommend for projects. “We have to find that link where we can trust the yard [and] have a clean settlement organization… and an owner who genuinely wants it to happen in the right way.”.

In order to ensure that EU SSR and HKC are adhered to in-practice, Mrs. Saltkjel noted that in contracts managed by Grieg Green, “there is a requirement that [Grieg Green] is supervising at the yard during the entire process of ship recycling …The main goal for us is that it was done in the right way and that it can be documented in full to the customer”.

Unlike class societies, Mrs. Saltkjel illustrated that companies like Grieg Green also consider several “subjective” factors when determining if they will add a yard to their own list of vetted ship recycling facilities. For example, Mrs. Saltkjel listed “cooperation, knowledge, management style, and commitment” as some of the subjective factors that Grieg Green considers when they determine if they will recommend a yard to shipowners.

“It is really important to us to work with the yards where the management has been involved in the documentation themselves so they have really understood what they are promising and they are making procedures that fit the actual equipment and work cultures that they have”.

When describing the ship recycling process, Mrs. Saltkjel noted “it has to be a very structured process. For recycling a specific ship or rig you have to make a Ship Recycling Plan, which is a vessel specific addition to the Ship Recycling Facility Plan detailing the steps from delivery to completion”. Stressing the importance of the IHM, Mrs. Saltkjel pointed out that “you detail [in the specific Ship Recycling Plan] how you are removing each of the materials. From going onboard and marking the location of the materials listed in the IHM to stripping all materials and inventory and finally cutting the steel in a safe manner. The IHM gives estimated weights or volumes. As material is removed from the ship, consultants from Grieg Green will track the amounts versus the IHM to ensure that this material is accounted for through the entire ship recycling project. Furthermore, all of this material can be traced downstream to a licenced disposal facility”.

Given the ongoing public pressure on shipowners to ensure their legacy assets do not end up at one of these notorious harmful shipbreaking operations, it appears that the desirability of ship recycling consultants like Grieg Green are on the rise. Mrs. Saltkjel ended the interview noting, “companies in third worlds will make investments if it will give them business. So there has to be a balance. You cannot lean back and say that they have to fix everything so that its perfect and shiny, and then we’ll give them business. At some point in the development you have to test a yard with an actual ship recycling project to find out how theory fits practice. We always keep an open and constructive dialogue with both yard and previous owner in this process…That’s how you evolve…”.

Read For Ship Recycling, Grieg (Goes) Green in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of November 2019 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from November 2019 issue

Content

- Training Tips for Ships: Taking the Stress out of Tests page: 10

- Training Tips for Ships: Taking the Stress out of Tests page: 10

- Risk & Reward of The Internet of (Maritime) Things page: 12

- Five Common Mistakes in Maritime Contracts page: 14

- Taming Ferry Wakes and Reducing CO2 page: 16

- Prepare Now for 40,000 Offshore Wind Jobs page: 20

- Maritime Schools Must Prep for Offshore Wind Jobs page: 20

- Offshore Wind: Decisions Needed Sooner, not Later page: 22

- Offshore: OSV Market Report page: 28

- Interview: Ed Grimm, CEO, Southern Towing Company page: 34

- USCG PSC Equals meaningful Polar Presence page: 44

- For Ship Recycling, Grieg (Goes) Green page: 52

- Interview: Boriana Farrar, Ship Owners Claims Bureau page: 66

- Scrubbers: A "360-degree solution" for Owners page: 72