Maritime to Get Biggest Bang for VW Settlement Bucks

By Patricia Keefe

With $2.9 billion available, tug and ferry engine upgrades are best bet for NOx reductions

Imagine a settlement over falsifying emission levels in another transportation sector dropping money onto your deck. Who knew? But it’s true. The $2.9 billion settlement fund Volkswagen agreed to capitalize for distribution across all 50 states, tribal lands and Puerto Rico, as a result of “dieselgate,” its criminal dodging of required auto emission levels, presents an unparalleled opportunity to maritime companies that want to move their noxious diesel engines up a couple of EPA notches, and stick someone else with close to half the bill or more.

The settlement is “unprecedented in its sheer scope of funds, geographic reach and market-moving potential,” according to Joe Annotti, senior program manager with transportation consultants Gladstein, Neandross & Ass. (GNA). “This type of thing just doesn’t happen,” he says, comparing it to the Energy Department’s $300 million Clean Cities Program expressly for alternative energy vehicle projects. “That’s 900 percent smaller than the VW settlement.”

From the state’s perspective, there is no better use of the funds than to clean up marine diesel engines, adds Annotti, calculating that in terms of tonnage of NOx reduction for dollars spent, the cleaning up of marine diesel engines is the most cost-effective by virtue of the number of hours they operate, the amount of fuel consumed and the emissions profile of the engines currently in use.

Annotti heads up GNA’s Funding 360 program, which has a free VW Funding Project Competitiveness Calculator, and a subscription Portal, that provides access to information about state-specific VW Funding programs.

Under the rules of the Volkswagen Mitigation Trust Fund (see related story Dieselgate 101.txt), tug, tow and ferry owners with qualifying NOx emissions reduction projects can get the job done at a significantly reduced cost, the extent to which will depend on the engine upgrade option they choose, and whether the patient is privately or publically owned.

In the latter case, projects, whatever they may be, are 100 percent funded. That’s why, and how, Washington State is hoping to build, and pay for, three new all-electric state-run ferries. Officials there estimate that a single such ferry could cut carbon dioxide emissions by 620 metric tons a year, the equivalent of taking about 132 cars off the road. It also cuts fuel consumption 100 percent.

In the former case, owners of commercial vessels running on pre-Tier 3 diesel engines can get back 40 percent of the cost of installing a new Tier 3 or Tier 4 diesel or alternate fuel engine, or by installing an EPA-certified remanufactured system or verified engine upgrade, in this case moving pre-tier or Tier 1 engines to T2. According to the EPA, Tier 4 rules cut NOx by 80 percent and particulate matter (PM) by 91 percent.

Go all-electric and you can get 75 percent of the cost covered, plus additional monies to install charging stations and related equipment.

Apply under the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) option, which is allowed under the trust rules, and states can use trust funds to match the DERA grant, and in doing so, reap an additional DERA bonus equal to 50 percent of the base sum. It’s manna from heaven, basically, to do work that needs to be done.

It just can’t be mandated or already scheduled work. “There is a requirement to show funds will be used in a situation to reduce emissions where it might otherwise not happen,” says George Lin, Technical Manager, Global Regulatory Affairs, Global Marine, Caterpillar, Inc.

But it could be used think bigger, and greener, notes Buckley McAllister, president of McAllister Towing and Transportation Co., Inc., and a veteran of several incentive grant projects. “A major overhaul can exceed a half million dollars, and if you factor that into the concept of installing a new engine, and that gets you a subsidy and a main engine that will require less maintenance than a 30-year-old engine, it’s a great thing.”

There are other incentive programs targeting environmental improvements, but the types of projects allowed and the competition for those dollars is much broader. By comparison, the Volkswagen MTF is narrowly focused on cutting PM and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, which contribute to smog, and in the case of the maritime sector, only available to two specific classes of vessels – which must operate solely in U.S. waters – tugs, tow boats and ferries.

“The marine sector still has the dirtiest engines out there. It should have a great shot at mitigation funds,” says Elena Craft, a public health scientist focused on air pollution for the Environmental Defense Fund. “If you want to prioritize NOx reductions, more so than any other projects, they have not been touched!” The VW settlement is a “game changer for maritime,” which she says is starting to come around to the need to improve air quality. “These kinds of funds don’t come around very often. If you have the means and ability to take advantage of this opportunity, you definitely should.”

Everyone’s a Winner

The Volkswagen settlement is also an incredible boon to states desperate to green transportation, but lacking the funds or control to do more than a bit at a time. While the amount each state receives will vary, depending on the number of illegal VW vehicles registered inside its borders, the money puts each in a position to map out a 10-year emissions reduction plan and to dedicate specific monies toward specific goals. And for those coastal and brown-water states looking for the fastest, cheapest and biggest reduction bang for the buck – the marine sector can’t be beat.

“If you take one of these pre-EPA Tier engines and upgrade to one of the newer engines, the emission reduction is dramatic,” says McAllister, who has installed some of the first Tier 4 engines (Caterpillar 3516) found on tugboats.

As one example, according to the Diesel Technology Forum (DTF), of the roughly 47 marine workboats in New York Harbor, 28 are powered by pre-emission standard engines. Swapping out an older “uncontrolled” engine for a Tier 4 engine in just one old tugboat removes an estimated 96,000 lbs of NOx per year, equivalent to replacing 76 older trucks or removing 74,000 cars for one year, according to a new report on “emission reductions and cost-effectiveness for marine and locomotive projects,” from the DTF, a diesel industry organization, and the Environmental Defense Fund.

By comparison, marine transportation consultant Paul J. Moynihan, vice president, technical services, M.J. Bradley & Ass. LLC, estimates that a rough approximation of the total tons reduced and equivalent trucks replaced and cars removed from the road by going to Tier 3 instead of Tier 4, might be somewhere in the neighborhood of 76,000 pounds NOx reduced annually, 60 old trucks replaced and 58,500 cars removed for one year.

In other words, upgrading the engines in a few vessels is far more cost-effective for states than upgrading a fleet of city busses, especially since, by some estimates, the lifetime mileage-weighted average NOx emission factors for diesel school buses has already been slashed by roughly 92 percent. Which means the achievable emission reductions from upgrading buses won’t come anywhere close to what’s achievable with a marine project, while also taking longer and being more work to manage, since each bus would be a separate project. With so many states eying this option, the fact that there is only so much bus manufacturing capacity in the U.S. per year, would make even a 25-bus fleet overhaul a multi-year project, adding even more time onto the wait for a lesser overall emission reduction, notes Moynihan.

So Why Wait?

Hands down – harbor craft and river vessels are the oldest and dirtiest spewers of NOx pollutants out there (see charts for ferries and tugs). Many pre-EPA tier engines are still cranking away like a diesel version of the Energizer Bunny. Diesel engines, like the craft they power, were built to last for decades.

There are fully functional 50-year-old tugs capable of doing a great job, and new engines are expensive. In an industry hidebound with environmental regulation, there isn’t a one forcing upgrades. (Emission levels aren’t really regulated beyond the highest EPA Tier in effect the year an engine was installed.)

So what we have is an unparalleled opportunity to upgrade or replace engines at a significant cost reduction versus no legal or regulatory incentive to do so.

In its absence, by 2020, the EPA has been estimating that only three percent of tugboats, and five percent of ferries, will be running on the cleanest available tier engines, i.e. Tier 4, which produces “near zero” emissions.

The hope is that trust fund will motivate vessel owners to more quickly lower the industry’s emissions output.

“These grants really help people get technological advances for their fleet in an affordable manner,” says McAllister.

Still Up in the Air

As the states work their way through their own approval process, collecting public input and writing mitigation plans for allocating their share of the trust, potential applicants are waiting to see which states are committing how much to marine initiatives, what the application process involves, and how the settlement money will be dispersed.

So far, California’s Air Resource Board says it expects to split much of that state’s $423 million on electrification projects and existing emissions reduction programs targeting areas near warehouses, industries and seaports. Pennsylvania is reserving 55 percent of its $110.7 million share for rail and tug engine replacement projects. Maine is committing 40 percent of its $21 million to improvements in ports and rail yards. And notes CAT’s Holt, Missouri has a lot of barge traffic while all the waterways meet in Paducah, KY.

Also unclear are answers to several questions that would impact the ability of some harbor craft, workboats and ferries to garner a share of these settlement dollars:

* What about vessels that traverse a regular route that takes their emissions through several states - which, if any state, do they apply to? “For inland waterway folks, go up and down the Mississippi and hit eight states – which state gets to pay for it?,” says Moynihan.

* Would states be willing to collaborate, to split the cost of funding a qualifying application involving a vessel that runs between both states? By splitting the bill, each state could win some emissions credit at half the cost of a NOx reduction project, notes MJB’s Moynihan.

* Will a company based in one state with a vessel that spends most of its time working the waters of another state, be able to submit proposals in both states? Some transportation consultants think the answer is yes. States, like the EPA’s DERA program before it, will focus primarily on the history of where each vessel operates.

Brace for Impact

Additionally, there are business impacts to consider with a diesel repower or replacement. For one, it won’t necessarily lower fuel consumption, and it might raise it, which increases carbon output. Switching to biofuels reportedly can reduce engine performance. “The efficiency of engines will decrease the more emissions reduction is applied,” according to McAllister, adding that while the older engines tend not to be super fuel-efficient or have the greatest emissions, they “have a lot of raw power.”

Some vessels have limited space in their engine room, and you can’t necessarily rearrange the chairs under the deck, so to speak, on an older vessel. Some paths to cleaner diesel, such as selective catalytic reduction, require more room for additional components, such as pipes and an air-cooled tank to hold urea. The new engine block might not be the same size as the old, exhaust systems might need to be increased, the entire gear box may have to be changed and installation may require cutting through decks, piping and steel.

A new engine can change the weight and balance of the vessel. “It’s not like a car engine,” says David L. Holt, Energy & Transportation Industry consultant for Caterpillar Global Aftermarket Solutions. “A lot of engineering goes into a vessel, and it may not be possible to replace the existing engine with a current tier engine.” Manufacturers like Cat and Cummins, Inc., sell alternatives to a new engine for these instances – kits or systems that upgrade to T2 or T3 that can be done inside the engine room.

The maintenance needs of modern engines are still unclear. This isn’t your father’s power plant. Tier 4 engines, says McAllister are “delicate and complicated.” New engines, even upgrades, tend to involve more electronics and software, which McAllister says can’t be repaired by a traditional mechanic. “Repairs can end up being much more involved than readjusting some mechanical aspect of the engine. So engineers on our tugs have to be half IT people.” Adds port engineer Mario Dezelic, a 31-year veteran of the Port Jefferson ferry,“The days of the ‘shade tree mechanic’ are gone. Now people go onboard with a laptop.”

That nice new dashboard feeding off new sensors means more information about the status of the engine and its myriad related equipment, leading to more engine checks. Problems may require more vendor assistance in order to diagnose and correct the malfunction, says McAllister.

And the state paying for reduced emissions will want to make sure it gets those benefits. Be aware that some incentive programs come with geographic restrictions, cautions McAllister. That won’t work for every vessel, he notes, pointing out such requirements would have prevented his vessels going to Puerto Rico for FEMA to assist with sealift after the September 2017 hurricane.

Why Do It, When You Don't Have To?

Because the pros far outweigh the cons, says just about everyone tracking emissions. It’s better for the environment, it’s better for the health of your employees, and it’s better for your business. “You can get a new engine for what it costs to rebuild an old engine, and you get a better operating vessel,” says port engineer Mario Dezelic, a 31-year veteran of the Port Jefferson ferry.

Besides the desire or pressure to run a green operation, an upgrade alone can add 23 years to the life of an engine, says CAT’s Holt, who explained that CAT’s certified upgrade kits that can take a “dirty, noisy, smoking” 1996 pre-T1 mechanically-based engine, keep the same engine block, change out the major components and make it conform to a much cleaner 2006 T2 engine standard, and operate at that standard for the next 23 years. Keep the rest of the vessel shipshape, and your workhorse is good for another generation of dependable performance.

“You get a fully electronic, computerized engine with incredible control over the vessel from a handling, acceleration performance and engine fault codes perspective,” Holt says adding, “It’s like moving from a 1980s car to 2017.”

Cleaner engines that run more smoothly and generate less noise are a plus for your crew and passengers. It’s a plus for the riverways and oceanic highways, and surrounding communities on land and in the water. Fewer emissions of all kinds, leads to less smog and acid rain, fewer health problems and less eutrophication - the excessive depositing of nutrients into waterways. “The EPA estimates that every dollar in any diesel cleanup generates up to $13 in public health benefits,” says GNA’s Annotti.

Mitigation projects can earn environmental credits that owners can use or sell. And are required in California, which has laid down a timetable by which vessels have to upgrade through the various EPA Tiers in order to do business in its waters. The only state to enact its own emissions regulations, they are unlikely to be the last. Other states are building Tier requirements into bids. Andy Kelly, marketing communications manager, Global Marine, Cummins, Inc., says a requirement in a New York state RFP that engines had to be Tier 3 or T4 lead Norfolk Tug Co. to repower four to five vessels.

Carpe Diem!

There seems to be near-universal agreement that along with locomotives, replacing the engines of tugs and ferries old enough to have carried your parents, if not your grandparents, is urgently needed. These old workhorses can generate as much as 40 times the emissions of a Tier 4 engine, which coincidently, is exactly the problem wrought by VW’s deception.

The newer diesel engines radically reduce a vessel’s NOx emission (see charts) even more so than projects involving many more trucks, busses or even multitudes of more cars. To recap. a handful of marine projects is cheaper to fund, easier to manage and track. There is simply no comparison in terms of the cost-effectiveness, speed and NOx reduction impact of upgrading diesel clunkers on ferries and tugs. Marine engine upgrades and the states’ settlement mandate are a match made in heaven: States should be lining up to give free money to tug and ferry operators.

Fish or Cut Bait

Operators that don’t try to take advantage of this unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity may down the road find themselves forced to cut emissions.

Manufacturers have already pushed diesel engine emissions down to near zero with Tier 4 technology. As the movement toward all-electric and zero-emission vehicles grows, and that technology and capacity starts to catch up with demand, it’s going to become harder for tug, tow and ferry operators to ignore the fact they are rapidly sailing alone in the haze. The expectation among transportation consultants, industry organizations and environmental concerns is that if business and health gains from greener operations don’t force a change, eventually, regulators will. And by that point, the cost of doing so will have grown exponentially while the settlement funds will have been spent.

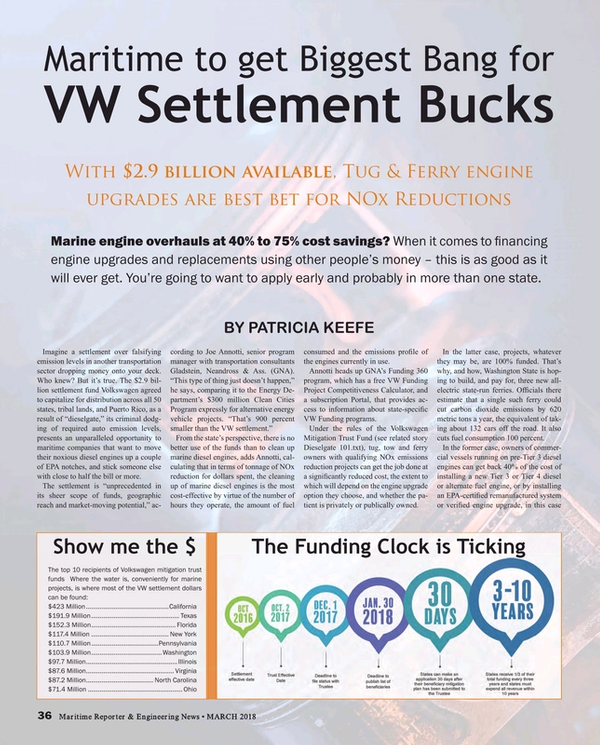

It’s a heck of a worm the early birds are going to catch here. Technically, operators have 10 years to apply for the money, but the funds are expected to run out in the first three years in most states. The first projects will probably kick off in early summer.

None of this is lost on engine makers like Cummins, Inc., and Global Marine Caterpillar, which are said to own 85 percent of the marine engine market. Both are working hard to promote the benefits to funding marine initiatives. Cummins for example, put together a strategy team to lobby states for inclusion of a maritime category, while CAT is developing a program to prepare dealers to assist customers with their trust fund applications. CAT is targeting the more than 1,000 3500 series engines it sold between 1993 and 2004, which it believes would qualify for trust fund monies using CAT Emissions Upgrade Kits.

Both companies maintain that the market for all-electric isn’t quite here. The infrastructure needs to be put into place, and power and size limits of batteries need to be addressed. “The technology has not developed to the point where it can really change the segment,” says Chad Hoey, director of sales for marine engines, Cummins, Inc. Annotti is a little more positive. He says electrification can work for “captive fleets’ the work out of a port and or within small, confined operating territories where vessels come back to the same locations repeatedly.

Meanwhile, clean diesel is here today, and upgrade kits are being positioned as a more affordable alternative to installing new engines. “Not only are customers getting an emission upgrade, they are also getting new-like engine condition and up-to-date technology, adding decades of reliable operation,” says Holt. Total cost of ownership is cut by the reduction in needed major overhauls over the life of the engine, he adds.

The potential windfall here is also a boon to engine manufacturers. Given the target audience, most are focusing their efforts on selling upgrade kits. And while they do not have the benefit of a government mandate, the companies say they don’t need it. The ROI on cleaner engines speaks for itself.

In case it doesn’t, Cummins has created an emissions calculator for customers to use to see how much their engine upgrade or swap out project can reduce their NOx emissions (See graph and sidebar Tools.x)

The EPA’s grim expectation for a slow steam toward emission improvements among tugs and ferries doesn’t have to be that way.

While the states seek the most bang for their emission reduction dollars, smart operators will seek out the most bucks for their engine upgrade bill, Now is the time to is work with your engine dealer or state’s designated VW Trust agency, figure out and check your emission reduction strategy, plot your states, and get in line for lots of green to help reverse the damage done and ensure clean sailing ahead.

“This is a unique opportunity, there aren’t many [programs] of this magnitude. There aren’t any other Mitigation Trust Funds or consent decrees being set up,” reminds CAT’s Lin. “If you miss this opportunity, there won’t be another as significant in the future.” Agrees Holt, “The sooner people apply the better, once these funds are gone – they are gone.”

Need Help Estimating NOx Reduction?

Need help figuring out the eligibility of your project? Vessel owners can avail themselves of a variety of tools designed to calculate the likely emissions savings, cost and competitiveness, of their engine updates. Here are a few options: The Global Marine division of Cummins Inc., has developed an emissions estimator (see screen shot) that it says can help calculate the emissions produced by previous Cummins products and emissions produced by EPA Tier 3 Cummins products. “These estimations are derived from test cell and emissions certification data and may vary depending on engine life, duty cycle and fuel quality,” says Global Marine’s Andy Kelly, Marketing Communications Manager.

Gladstein, Neandross & Associates (GNA), consultants specializing in low-emission and alternative fuel projects, has a free VW Funding Project Competitiveness Calculator on its site. Fleet owners can input their fleet size, current fuel, and planned fuel to receive a recommendation on their possible funding eligibility, according to GNA’s 360 Funding team, which helps companies track, evaluate, and apply for funding programs throughout the U.S. and Canada.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Diesel Emissions Quantifier (DEQ), which it says “specializes in estimating emissions from medium-duty and heavy-duty diesel engines. DEQ is frequently used to estimate diesel emissions reduction from the repower or replacement of diesel engines with newer diesel engines and the use of emissions control devices, for DERA projects. Fortunately, GNA’s Funding 360 team has researched, read and distilled down all of the important details so fleet managers, technology providers, and fuel suppliers can identify the best incentives for their projects.

(As published in the March 2018 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News)

Read Maritime to Get Biggest Bang for VW Settlement Bucks in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of March 2018 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from March 2018 issue

Content

- The US Government Must Fund Icebreakers Now page: 12

- American Pride: Working Hard in the US Dredging Industry page: 16

- Interview: William Harber - Hurtigruten, Americas President page: 18

- Interview: Angus Frew, Secretary General, BIMCO page: 24

- Corrosion Control and the Autonomous Ship page: 28

- US Navy: 355-Ship Fleet is the Mandate, Funding It is Fuzzy page: 32

- Maritime to Get Biggest Bang for VW Settlement Bucks page: 36

- Dieselgate 101: Opening the Door to Cleaner Engines page: 45

- Practical Contributions to the Development of Autonomous Sailing page: 46

- Production Floaters Orders Are on the Rebound page: 50

- Maritime Simulation: High-tech Meets Practical Skills page: 57

- Latest Innovations in Heavy Duty Machinery page: 62