WWII Museum’s PT Boat Readies for Passengers

A cadre of volunteers navigate the regulatory labyrinth and a host of safety requirements to bring back to life an enduring symbol the nation’s can-do spirit and resiliency.

Early next year, a 78-foot Patrol Torpedo 305 boat, being restored at the National WWII Museum, should be U.S. Coast Guard compliant and ready for passengers. The fast-attack PT-305, equipped with cannons, torpedoes and machine guns, served in the Mediterranean in 1944 and 1945, operating from Bastia, Corsica. PT boats fired at warships, mainly under cover of night, and then fled at speeds of up to 43 knots, making it difficult for enemies to retaliate. The overhaul of PT-305 started at the New Orleans museum eight years ago.

Rich History

The boat, built and commissioned in1943, was among 199 produced by Higgins Industries in New Orleans. New Jersey-based Elco was the biggest builder, churning out a total of 385 PT boats in a number of U.S. yards, and Huckins Yacht Co. in Florida was another producer.

The Higgins and Elco designs used a planing-type hull, developed for racing boats. The PT-305, with a sharp V at the bow that softens to a flat bottom at the stern, lifted out of the water at high speeds. With a layered hull over a wood frame, these vessels were light, but strong and resilient enough to stand up in heavy seas, Robert Stengl, the National WWII Museum’s boat builder and logistics engineer, said last month. The PT-305’s wood construction allowed it to be repaired near the front lines.

A number of PT boats were set on fire when WWII ended. But PT-305 was sent to New York in 1945, auctioned in 1948, and put to private use as an oyster boat in Chesapeake Bay until 2001. “Thirteen feet of boat were removed from the stern before it began collecting oysters,” Stengl said. That was to avoid a regulation that vessels over 65 feet have a Coast Guard-licensed captain. In 2001, PT-305 was acquired by the Defenders of America Naval Museum in Galveston, Texas. Five years later, that institution contacted the National WWII Museum about taking over the vessel’s restoration. The boat was moved to New Orleans in April 2007.

Volunteers and Donations Defray Costs

Work on the vessel, now housed in the John E. Kushner Restoration Pavilion, is about two-thirds done, Stengl said. He’s in charge of collecting new and vintage spare parts from U.S. and foreign donors, and he oversees a cadre of volunteer craftspeople. ”Over a span of five years, our restoration crew has had 195 total volunteers,” he said. Sixty are donating their time now. “We have one WWII veteran, Jimmy Dubuisson, who is 87 years old and working on the PT boat,” Stengl said. “His contributions are huge. And as the cofounder of Halter Marine in Mississippi, he introduced us to his supply chain.”

To make the boat fully operational, some designs had to be modified. ”The challenge is to restore the vessel to historical accuracy while making it compliant with today’s Coast Guard standards,” New Orleans-based volunteer and naval architect Mark Masor with Gibbs & Cox in Virginia said.

The vessel will be launched in Lake Pontchartrain in early 2016. After that it might visit several ports along the Gulf Coast. “Once the restoration is complete, PT-305 will go back on the water in an as-yet-determined capacity,” said Kacey Hill, spokeswoman for the National WWII Museum. “A number of options are being explored for the boat. But the first step is to have it certified by the Coast Guard to carry passengers.”

The project’s volunteers include boat builders, engineers, electricians, mechanics and carpenters. “These men and women have various work experiences and professions, and give their time to make a difference and honor fighting sailors,” Hill said. “A few are retired and do hands-on work on the boat.” Many are veterans knowledgeable about military equipment.

“We began this restoration with six WWII volunteers five years ago, and our remaining volunteer vet from that war, Jimmy Dubuisson, serves as the project’s brain trust,” Hill said. The project’s price tag, which could have been several million dollars, has been reduced by voluntary labor and donated parts and services. The projected cost of restoration is about $1,425,000, Hill said. “That doesn’t include estimates for mobilization and operation once the restoration is complete,” she said.

“Volunteer work is done in a matrix organizational structure, with very little top-down management,” Hill said. “The work atmosphere allows innovation by individual contributors, leading to or influencing broad solutions. No one volunteer is more important than another.”

No Easy Task

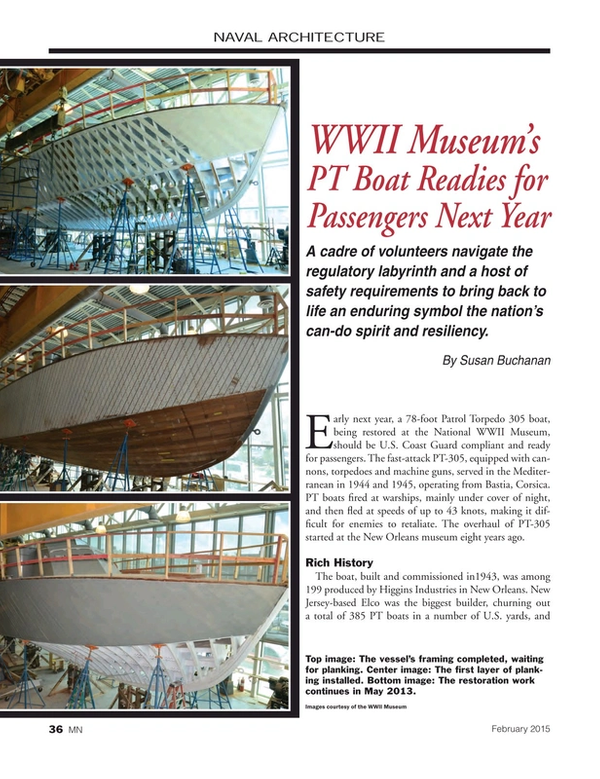

Restoration workers have replaced about 80 percent of the boat’s original wood. In 2009, workers found that the deck and the ribs supporting it were damaged. After decades of wear and tear, the deck’s ribs had failed, planks had rotted and screws were corroded. Moreover, the deck had suffered structural deterioration.

The wooden boat’s planking provides most of its strength. When the deck was removed in 2010, it was evident that the ribs had de-laminated after the glue failed, flattening the deck and leaving it unsound. The ribs were removed, measurements were made, sections of hull were restored, and material was ordered before the deck was laid again.

In 2012, PT-305 was re-outfitted with 80-foot deck boards. An inner layer of three-inch mahogany planking was laid diagonally across the deck’s length in August 2012. This layer rests on the deck ribs and acts as the roof for crew members when they’re inside the boat, Masor said.

While the inner layer was laid, a covering board was completed and production began on the top layer of deck boards. The top deck boards are 5/8 of an inch by 2-inch mahogany planks, spliced together to create boards up to 80-feet long. Mahogany keeps the boat light, while making it strong. These deck boards run fore to aft on the length of the boat, except for its center section – which contains the chart house and engine room hatch.

The completed deck is one inch-thick, with an inner 3/8-inch planking; a layer of Dolfinite, which is a bedding compound used to waterproof joining layers of wood; a layer of canvas; another layer of Dolfinite and the top layer of 5/8-inch deck boards. This assembly is screwed to every deck rib and riveted together between every deck rib. The deck was installed with canvas and Dolfinite.

According to the workers, Dolfinite, trademarked by Dolphin Paint & Varnish in Ohio, sticks to everything in its path. Dolfinite duty on PT-305 has produced tales of what the substance did to clothes, hair, tools and emotions. But some of the original Dolfinite on PT-305 remains moist, and the stuff really works. The rebuilt deck feels very solid underfoot, especially compared with wood floors in New Orleans houses.

Inside and Below Decks

The deck house, constructed of mahogany frames and containing a chart room and radar room, is on the PT-305’s main deck. The aft end of the deck house has a steering and propeller control station, along with a windscreen and storage compartments. Ammunition storage lockers for cannons are on the deck. A radar mast and radar dome was located on the deck’s middle. Navigation and survival equipment, including a life raft, were mounted on the deck. Mark Masor adds, “About twenty cowl scoops and clamshell vents all over the deck support natural ventilation. Some of them are fitted with mechanical blowers to force air into living and machinery spaces.”

The PT-305’s interior is divided into watertight compartments. Starting at the bow is a chain locker, where anchor chains, lines and deck gear were stowed. Next is the forward crew’s quarters and galley, which contain bunks on each side; along with lockers; cabinets and a gyro-compass sensing unit. The next compartment aft, to the rear, is the officer’s wardroom, with two berths, a desk, radar equipment, small-arms weapons and ammunition lockers. Aft of the wardroom is the forward tank room, with two 800-gallon gasoline tanks flanking either side of the officers’ head.

The next compartment aft is the engine room, which will contain three engines, auxiliary electric generators and an electrical DC switchboard. Volunteers have restored three Packard Marine V12 Engines 4M-2500s and are working on a fourth. The PT-305 had three such engines, using 100-octane aviation gasoline. When the vessel was converted to an oyster boat, the equipment was replaced with two diesel engines.

The boat can carry 3,000 gallons of fuel, giving it a cruising range of over 550 miles. Fuel is carried in the forward tank room and in the aft tank room, located aft of the engine room. Near the stern back end of the boat is a store room and lazarette/steering gear room, which contains four crew bunks and the rudder steering gear. In WWII, the PT-305 carried eleven crew members and two officers, or a total of thirteen.

Balancing Historical Accuracy with Regulatory Compliance

Three marine professionals – naval architects Masor at Gibbs & Cox and Don Luparello at Thomas Sea in Louisiana, along with the museum’s boatwright Bruce Harris – are among those guiding the project. “They’ve kept the vessel’s reconstruction on track and in concurrence with federal regulations,” Hill said. The U.S. Coast Guard is helping the project navigate the certification process. Gibbs &Cox Naval Architect Masor adds, “In particular, our local senior marine inspectors, Douglas Olson and Thomas Alho with the USCG Sector New Orleans, Domestic Vessel Inspections Branch, have been tremendously hands-on in lending their expertise.”

PT-305 will have its original fuel-system configuration, and will use aviation gasoline or AvGas. “The sounds, smells and performance of the Packard aviation gas engines are part of the vessel’s historic essence so it was important to retain it, even with operational challenges,” Masor said. AvGas has a much lower flash point than diesel fuel, making it very flammable and combustible if exposed to sparks, flames and heat, he said. AvGas vapors accumulate in low spaces, such as bilges and other pockets in the vessel. The original PT design provided safeguards, combined with documented operational procedures that successfully mitigated these risks.

To meet today’s regulations for passenger safety, new safeguards were added. An upgraded, CO2 firefighting system was installed in work led by volunteer Stephen Kramer and his company Herbert S. Hiller in New Orleans. Other innovations on the vessel include more ventilation; ignition proof lighting; electrical interlocks; vapor detection; and modern, programmable logic controller or PLC-based monitoring, alarm and control systems.

“Most of these safeguards are being implemented while maintaining the look of the original configuration,” Masor said. “For example, additional electrical equipment is installed in a secured ammo locker below deck. This storage, which held over a thousand pounds of ammunition, is ideal for today’s heavy electrical equipment, and its use maintains the vessel’s original center of gravity.”

When the museum decided PT-305 would carry passengers someday, Masor began working with the Coast Guard on vessel certification. “That entails plan or drawing reviews for approval by the Coast Guard and coordinating in-progress work reviews of the boat,” Masor said. “Since passenger and crew safety is the highest priority, we analyzed intact and damage stability, fire-fighting, lifesaving appliances, bilge and navigation systems.” Naval architect Don Luparello has volunteered on the project since its start, and marine electrical engineer Jim Buchler with Pelican Energy Consultants in Louisiana is overseeing upgrades of the vessel’s electrical generation and distribution systems.

The Effort Continues: here and abroad

The hunt for no-longer-produced parts and components continues. “The volunteers’ search for parts has involved detective work, the internet and plain luck,” Tom Czekanski, director of collections and exhibits at the National WWII Museum, said. “Their search has been worldwide. The vintage radar was found in Australia, and the Packard engines were located in a farmer’s barn in Illinois.”

Items which Stengl and volunteers have collected or continue to gather are: Packard Marine V12 Engines 4M-2500, complete and in parts; auxiliary generators, including a Capital Motors 5.5kw Generator, US Motors 2.5kw Generator; demilled armament, including a Mk9 Cradle Machine-gun; two 20 mm Oerlikon deck mounts; Higgins PT boat operating and maintenance manuals; chart house navigational accessories; galley components, including a bread toaster made by the former Toastwell in Missouri; and modern navigational equipment. The project is also gathering PT boat photographs, albums, photos and movies.

The National WWII Museum conducts tours of PT-305 daily at noon. “It’s suggested that you sign up at the ticket booth for these tours, which are no cost to visitors,” Stengl said. A handful of PT boats exist in the United States today, and one, Higgins PT-658 at Swan Island in Portland, Oregon, is operational. When PT-305 sails next year, its converted ammunition boxes will provide seating for passengers. PT-305 didn’t have a full name in WWII but was known by sailors as The Sudden Jerk, The Bar Fly and The Half Hitch.

The worthy effort to restore and preserve a rich piece of naval history – and naval architecture itself – continues with enthusiasm in New Orleans. With dedicated volunteers like Mark Masor from Gibbs & Cox and a host of others, and a hands-on Coast Guard sector that embraces the project, its ultimate success is all but assured. The can-do spirit of America’s so-called “Greatest Generation” is clearly alive in well in the Big Easy and coming soon to a port near you.

(As published in the February 2015 edition of Marine News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeNews)

Read WWII Museum’s PT Boat Readies for Passengers in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of February 2015 Marine News

Other stories from February 2015 issue

Content

- Editor's Note: Energy Market's Double-edged Sword page: 6

- Insights: Rear Admiral Paul F. Thomas page: 12

- The Quest to Fund Inland Waterways page: 18

- Moving Ahead With the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund page: 21

- Avoiding Pitfalls on the Water page: 22

- A Gift to US Inland Waterways page: 26

- Propellers: One Size and Shape Does Not Fit All page: 28

- Powering Ahead with a Clean Design page: 32

- WWII Museum’s PT Boat Readies for Passengers page: 36

- In Safety, Quality Comes First page: 42

- Balanced Dredging with E-Crane page: 45

- Futuristic Bridge Concept by Rolls-Royce page: 47