Rough Waters for Washington State Ferries

Improved funding and management changes have the nation’s largest ferry system on a course to better times. Challenges remain, but WSF tackles each one in turn.

Unlike the citizens of British Columbia, which pays a German shipyard to build its ferries, Washington state residents resolutely invest at home. By law, ferries are built locally and the results, overall, seem win-win. The state’s Office of Financial Management estimates that every $75 million in ferry construction generates about $90 million for the state’s economy. In-state shipbuilding provides the vessels that are at the center of the marine transportation system. On top of that, WSF employs 1,900 people.

So, while the shipbuilding end of the ferry system has been successful, the funding end has struggled. It has sometimes seemed as though taxpayers were at odds with themselves, on one hand expecting transportation but with the other hand cutting its funding. A 1999 tax repeal began years of persistent underfunding. Lean budgets have forced WSF into using decades-old boats and gave it uncertainty about buying new boats. Lack of funding meant delayed maintenance and tight staffing. And, the situation gave shipyards little year-to-year certainty about new builds and set the stage for high-profile negative publicity.

Ferry Funding Fractured

Iconic green-and-white WSF ferries are the state’s single biggest tourist attraction. They’re also transportation for everyone from Bainbridge Island-to-Seattle commuters to long-haul truckers to personnel at the six naval installations around Puget Sound. As a “marine highway system,” ferries connect the mainland to the Olympic Peninsula and to highly populated islands in Puget Sound. WSF’s 24 ferries cover 10 routes and 20 terminals. WSF operations serve 60 percent of the state’s population, about four million people. It should therefore come as no surprise that WSF is the largest ferry system in the United States.

Voters may not have had long-term effects on ferries on their minds in 1999 when they repealed the Motor Vehicle Excise Tax (“car tabs”), taxes reserved for transportation and ferry operations since 1937. Ferries lost 20 percent of operating costs and 75 percent of capital funding. Hence, in the choppy wake for that questionable voter edict, WSF quickly found itself raising tolls and fees. Given higher tolls and service cutbacks, ridership sank from its peak of 27 million trips in 1999 to 22.6 million trips in 2010.

In 2007, a second blow came in the form of the overnight removal of four 80-year-old Steel Electric Class ferries. When tests showed that the hulls were dangerously corroded, transportation secretary Lynn Peterson pulled them from service that day. The ferry system ran very lean for the five years it took to replace them.

In the rush to replace those very old ferries, WSF botched building decisions for the first new replacement. WSF decided to use a preexisting ferry design from the Island Home, which runs between Martha’s Vineyard and Woods Hole, Mass. A 2013 state audit found that change orders caused the first replacement ferry, the Chetzemoka, to end up costing almost twice as much as the Island Home.

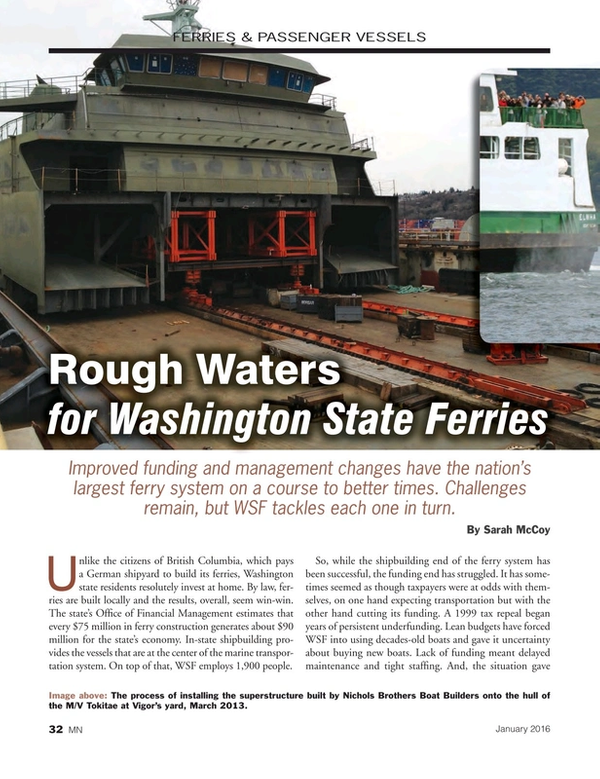

Nevertheless, the legislature funded new 144-car Olympic Class ferries built by Vigor in Seattle, with superstructure built by Nichols Brothers Boat Builders of Whidbey Island. The first, the Tokitae, was finished in 2014.

Ferry Follies

“Tokitae” means “nice day, pretty colors” in Coast Salish. Yet 2014 proved to be a summer of horrors for WSF’s ferry chief. Staffing shortages sometimes cancelled sailings. In July, the Tacoma lost propulsion on the Bainbridge Island to Seattle run and had to be towed back to Bainbridge Island. Repairs cost $1.8 million. The 202-car Wenatchee was already out of service, making two of the state’s three largest ferries unusable. In August, Seattle’s KING-TV ran a story pointing out that the ferry system was attempting to sell never-used generators it had bought for $5.3 million in 2005 for the sum of $300,000. There are still no takers.

On August 15, in Bremerton, WSF allowed some 1,600 passengers onto a ferry bound for a preseason Seahawks game in Seattle. Ferry staff mistakenly thought they had allowed too many passengers and called in state troopers to have 500 debark. Only later did the ferry system staff realize they had been wrong on capacity. But the PR damage was done.

Ferry employees were understandably demoralized. The WSF ferry chief wanted to move on. Not finding a suitable replacement, Peterson called off the first search. At $145,000 a year, the job wasn’t tempting to many from the private sector.

But then the stranded Tacoma and the mistaken passenger count in Bremerton tugged at Lynne Griffith’s heartstrings. Griffith, a 36-year veteran of the transportation industry, said, “I saw they had serious operational issues. My goal was to come on board and stabilize the situation. That’s what I do.”

Righting the Ship

Griffith started getting familiar with her new territory by riding every ferry route and stopping at all the terminals and maintenance docks. Griffith and Peterson also spent several days completing the training for able-bodied seaman, to the surprise of ferry workers. Griffith flattened the management structure of the system; fired four high-level administrators and brought in members of her own team.

Meanwhile, on the legislative side of state government, House Transportation Chair Judy Clibborn was lobbying legislators to vote for a transportation budget that would pay for maintenance and new ferries. The 2015 legislative session, balanced between a Democratic House and a Republican Senate, went into not one but three extended sessions. By July of 2015, the parties at last agreed on a long-term transportation package that helped stabilize WSF funding, though there was still no dedicated tax revenue stream. The deal paid for a fourth Olympic class ferry; new terminals in downtown Seattle and Mukilteo, just north of Seattle, and some deferred maintenance. There is an RFP pending to convert up to six of the Issaquah Class ferries to LNG, but as yet, no funds.

Today, it’s not as if the ferry system’s problems are over, but things are on the upswing. Vigor Industrial has completed two new 144-car ferries under budget in the past two years. Vigor will finish a third soon and undertake the fourth immediately. In the meantime, WSF hopes for better financial support. The oldest ferries in regular service were built in the late 1950s and the next oldest are the Super Class, built in the 1960s. WSF has continued to move passengers and cars and has come to the point where it manages to recoup 70 percent of its operational costs with tolls, a very high rate of fare box recovery.

Ridership is increasing. Ferries carried 23.6 million passengers in the past year and that number is expected to go higher in 2016. WSF reports there is growth in tourist trips and optional local travel and less in daily commuter traffic.

In addition, Griffith earns very positive reviews after more than a year on the job. Her orders from Peterson were to improve workforce coordination, invest in people, invest in maintenance and operations, update service disruption protocols, and work toward further capital investments. Griffith had a planned surgery and was not available to answer questions, but deputy and Chief of Staff, Elizabeth Kosa, filled in for her. She told MarineNews, “All of these reforms are either complete or under way,” said Kosa, adding “Morale has improved over the past year, but we’re not interested only in the rosy picture.”

The unused generators have not yet sold. So far in 2015, 17 crewmembers have been honored for saving 18 lives. A new San Juan Islands reservations system is working as hoped. Wait times, in the past stretching up to eight hours in the summer months, have been markedly reduced. “That’s a thing of the past,” says Kosa.

The new Olympic Class Tokitae and Samish had problems with cars bottoming as they drove onboard. They cost $308,000 to fix but, as Kosa points out, the vessels came in nearly $19 million under budget from Vigor. Separately, an official investigation of the football fan-packed Cathlamet uncovered a defective crowd counting clicker as the root cause, and WSF has said it won’t happen again.

WSF’s Board of Inquiry did an investigation and confirmed that the ferry Tacoma’s failure was characteristic of the manufacturer’s design, which led to modifications of electrical switchboard systems on the other Jumbo Mark II class vessels, Puyallup and Wenatchee. Kosa explains, “High-profile problems like the Tacoma’s loss of power can be tough to talk about, but that’s when a culture of accountability matters most …We took special care to listen to frontline engine crews as the team developed solutions to protect against issues like this in the future.”

Looking Ahead

WSF has a maintenance backlog of $241 million and a biennial budget that only supports half of its preservation requirements. Construction of the newest ferry will help, but won’t solve the problem of deferred maintenance.

The age of the vessels is still well over anything a private system would use. “All but seven [of 24] vessels are over 30 years old,” said Kosa. “However, we’ve built five vessels since 2010. The sixth is under construction and the seventh is in the pipeline. Building new vessels continues to be a top priority.” WSF would ideally have one relief vessel stationed in north Puget Sound, and one stationed in the south.

Despite running very lean, WSF has a 99.5 percent reliability rate. Beyond that, all vessels have been upgraded to meet EPA air quality standards. The first three Olympic Class vessels meet EPA Tier 3 standards and the fourth, the Chimacum, will meet Tier 4 standards.

Kosa said, “A few weeks ago, several members of the executive team were out riding a ferry in the northern Puget Sound during a nasty storm. The conditions were pretty rough—big swells, high wind, limited visibility. It was eye opening for our execs who don’t come from a maritime background. They got to see what our crews deal with out on the water, the conditions, the competing demands, the pressure of keeping our passengers safe and secure. Experiences like these help us stay focused on what’s really important when we make decisions back in the office.”

Today’s WSF has a steady hand at the helm and a weather eye on the horizon. What comes next for many aspects of the nation’s largest ferry system isn’t altogether clear, but at least one thing isn’t shrouded in the fog: the Washington State Ferry system is moving eagerly, full speed ahead, toward the next challenge.

The Author

Sarah McCoy is a journalist based in Seattle, WA. She has written articles for the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Business Ethics, among others. She enjoys living in the maritime neighborhood of Ballard on Puget Sound and sailing out of Shilshole Bay Marina.”

(As published in the January 2016 edition of Marine News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeNews)

Read Rough Waters for Washington State Ferries in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of January 2016 Marine News

Other stories from January 2016 issue

Content

- MarineNews Editor's Note page: 6

- Interview: Dave Anderson, President, Passenger Vessel Association page: 12

- Interferry: Aiming High in the Cause of Common Sense page: 18

- Ferries: An Economic Driving Force page: 20

- Searching for a Better Way page: 22

- SailSafe: A SEA Change for the Better page: 24

- Maritime Training: Keeping it Close to Home page: 28

- Rough Waters for Washington State Ferries page: 32

- Driving the Inland Waterways page: 38

- Interior Outfitting: Water & Air page: 44

- AlphaEye Allows Real-time Audio Visual Support page: 56

- Join Schedule 80 Carbon Steel Pipe Without Hotwork page: 56

- BlueTide Releases App to Manage Wireless Networks page: 56

- Drones Allow Surveys Without Scaffolds page: 56

- Commercial Vessel Medical Kits – Coastal & Offshore page: 56

- Sherwin Williams Heat-Flex Protects, Insulates page: 56