Digital Twins: Rivers, Oceans, Harbors Recreated

In 2001, George Burkley, a maritime educator, wrote a look-ahead article for Maritime Reporter and Engineering News, presenting the benefits and real-world payoffs from using simulators in maritime education. In the late 1990s, new tech and software advances were creating scenario programs that moved a student closer and closer to the realities demanded by, well, reality. “The future is here, and we are ready to simulate it,” Burkley concluded.

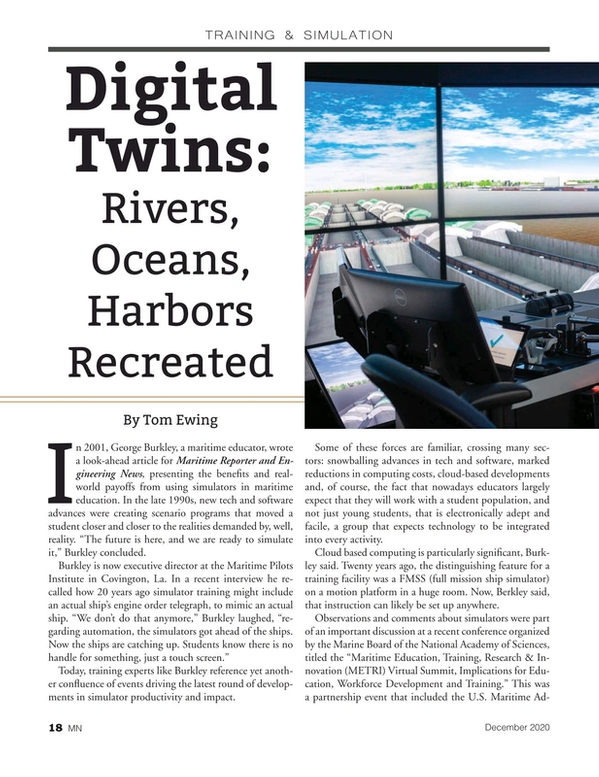

Burkley is now executive director at the Maritime Pilots Institute in Covington, La. In a recent interview he recalled how 20 years ago simulator training might include an actual ship’s engine order telegraph, to mimic an actual ship. “We don’t do that anymore,” Burkley laughed, “regarding automation, the simulators got ahead of the ships. Now the ships are catching up. Students know there is no handle for something, just a touch screen.”

Today, training experts like Burkley reference yet another confluence of events driving the latest round of developments in simulator productivity and impact.

Some of these forces are familiar, crossing many sectors: snowballing advances in tech and software, marked reductions in computing costs, cloud-based developments and, of course, the fact that nowadays educators largely expect that they will work with a student population, and not just young students, that is electronically adept and facile, a group that expects technology to be integrated into every activity.

Cloud based computing is particularly significant, Burkley said. Twenty years ago, the distinguishing feature for a training facility was a FMSS (full mission ship simulator) on a motion platform in a huge room. Now, Berkley said, that instruction can likely be set up anywhere.

(Photo: Maritime Pilots Institute)

(Photo: Maritime Pilots Institute)

Observations and comments about simulators were part of an important discussion at a recent conference organized by the Marine Board of the National Academy of Sciences, titled the “Maritime Education, Training, Research & Innovation (METRI) Virtual Summit, Implications for Education, Workforce Development and Training.” This was a partnership event that included the U.S. Maritime Administration, including Administrator Rear Admiral Mark Buzby, and top personnel from the maritime service academies, the maritime industry and federal agencies.

One break-out panel session, “Automation and Digital Leadership,” focused on emerging technologies, future vessel operations, and innovative and collaborative education and training programs.

Simulators, of course, are invaluable for high-risk occupational training, allowing practice without consequences and efficient use of personnel and space. Challenges can be added in sequence. Critically these days, they allow remote learning.

With simulators, these are attributes that get better and better and at decreasing costs. Programs are built from increasingly rich and varied data, from Internet-of-Things (IOT) data, for example, also increasingly available from actual operations, providing the basis to transform a real vessel’s real-world zeroes and ones into a simulator’s presentation.

Despite these attributes, however, panelists expressed concern that opportunities are not being maximized, that a kind of status quo has set in and that simulators as a resource are working at just a good enough kind of level. That needs to change. Some suggestions follow.

(Photo: MITAGS)

(Photo: MITAGS)

Gregg Trunnell is senior business development consultant with MITAGS – the Maritime Institute of Technology and Graduate Studies, with facilities in Maryland and Washington. Location, though, is of diminishing value. Trunnell sees a move to cloud-based simulator resources, providing training that is customized to a customer’s exact requirements, even to an exact vessel or set of operating conditions, and presented anywhere.

As he spoke to his virtual audience Trunnell pointed to six monitors set up in his home office. He was beta testing the concept of running three visual channels from home. “When the technology will allow multiple visual channels to be projected from the cloud, the possibilities are endless.” stated Trunnell. Anglo Eastern Maritime Training Centre in Mumbai, is already starting to run Bridge Resource Management training all remotely. And he noted that his home-based equipment was on the old side – five years old. “The world is moving quickly to cloud based simulation, and we very much need to stay ahead of this technology,” Trunnell said.

The biggest payoff: the huge expansion in the number of people who could access and take advantage of expert training. Instead of people having to travel to certain cities, to fixed-site facilities with inherent limits, cloud-based resources present as an almost limitless resource bounty.

Trunnell said this could happen even faster with organized cooperation among training providers. He said that providers – his organization, for example, as well as the maritime academies are not competitors; each draws customers and students from different maritime sectors: the military, for example, or harbor pilots, or cargo or passenger and cruise vessels. “Cooperation is critical,” Trunnell commented. “If we do the minimum, not much will change. But if we pool our resources, we can get it right. We can train a better mariner.”

Another big concern for Trunnell: the Coast Guard does not allow remote proctoring, although it does allow remote learning. “We won’t take the big steps forward until the Coast Guard changes its position and allows remote proctoring,” he predicted.

Captain Stephen J. Polk also participated on the leadership break-out panel. Polk is director of the Center for Maritime Education at The Seamen’s Church Institute, based at the Houston facility. Polk suggested a thought provoking, outside-the-box kind of goal for simulator training – using a digital twin as a kind of ultimate learning tool.

“What if you could train on your own vessel?” Polk challenged the audience. His question was built on a number of realities. Recall that simulation can be increasingly, singularly tailored. Note the reference above to IOT, real-time data for modeling, reducing dependence on what Polk called static “cookie-cutter data.” Another reality: at many maritime academies cadets, unfortunately, don’t get full simulator training until their senior year.

At the Institute Polk recalled how his team provided training on a boat that hadn’t yet been built. But it existed digitally, the twin of the vessel in the shipyard, under construction.

Polk referenced this project to make his suggestion: use a digital twin to similarly train maritime cadets. He further suggested that senior year is too late to start full ship simulator training. “Academies need to turn that around,” he said. Simulator training should start much earlier, preparing a cadet, by junior year, to make a choice about a vessel to specialize in – e.g., ships and ocean cargo, military, oil and gas exploration, harbor tugs, or tugs and barges working in oceans, inland, or western rivers. He or she would then start training in that competency area, and on those vessel types, at the academy, via the simulated digital twin. (Vessel standardization would also need to increase to really take full advantage of this idea.)

Polk called on educators to “create a scenario where education and training are done while in school, graduating a person who already knows the vessel.” He referenced many benefits – proving competence, impacting leadership, best practices regarding the vessel itself and, importantly, workforce retention. “To excel and improve,” Polk said, “we need to do more. Turn schools on their heads.”

(Photo: Seamens’ Church Institute)

(Photo: Seamens’ Church Institute)

Like Gregg Trunnell, Polk also suggested a shared, cooperative approach to advancing and maximizing simulator capabilities. “Our ability to access content from the cloud is a win-win. Take every advantage,” he advised the audience.

These new technological strengths raise an important, and maybe troubling, question: Can simulators alone completely train a captain or a pilot? Believe it or not – some say “yes,” at least for certain vessel tasks. Still, robotic prowess is not leadership. During the NAS Summit, one tow-boat industry participant commented that yes, we need and want employees with strong tech skills. Then he added: “But we need people who know how to look up from a screen and look out the window.”

George Burkley estimates that simulators can provide 20% of what it takes to be a captain. “Pilotage is a blend of art and science,” Burkley commented. “You can do the science part in a simulator. On the job training reinforces the art part. The brain learns differently when there are consequences.” A simulator can train for multiple options, but lessons usually present one condition at a time. “In real life, though,” Burkley noted, “you have to have plan A, plan B and plan C. The real world is still out there.”

Glen Paine is the Executive Director at MITAGS. He points out that advances in computer technology has made ship simulators a reliable tool for mariner assessments. MITAGS has developed a proprietary (Navigation Skills Assessment Program®) that uses simulation to assess mariner watchkeeping skills at the operational and management levels. Paine emphasizes that simulation is still “only one part of the complex training process for developing the next generation of mariners.” “Hands-on’ field experience is still absolutely critical.”

Paine says the challenge for training providers is ensuring that “traditional seafarer sense” skills are integrated with the technology. At the end of the day, Paine points out, “a mariner must know when the technology is failing and what to do about it.”

(Photo: Seamens’ Church Institute)

(Photo: Seamens’ Church Institute)

Read Digital Twins: Rivers, Oceans, Harbors Recreated in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of December 2020 Marine News

Other stories from December 2020 issue

Content

- US Inland Waterways: Cheer the Year! page: 8

- Wasted Words: Post-casualty Apologies Are ‘Sorry’ Excuses page: 10

- RIBs: Turn Up the Power page: 12

- Digital Twins: Rivers, Oceans, Harbors Recreated page: 18

- Marine News' Top Boats of 2020: James V. Glynn and Nikola Tesla page: 22

- Marine News' Top Boats of 2020 page: 26

- US Coast Guard Surf Boats: Service Life Extension page: 38

- Out-casting and Outlasting the Competition page: 40