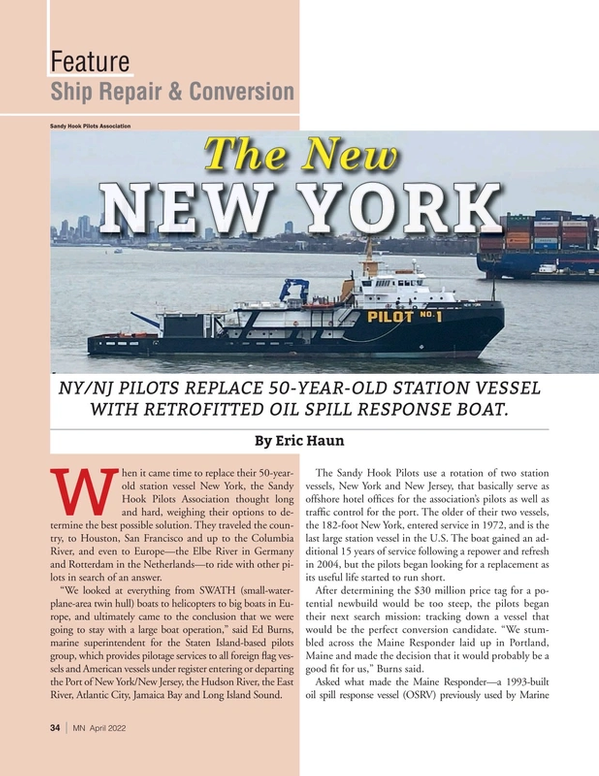

The New 'New York'

When it came time to replace their 50-year-old station vessel New York, the Sandy Hook Pilots Association thought long and hard, weighing their options to determine the best possible solution. They traveled the country, to Houston, San Francisco and up to the Columbia River, and even to Europe—the Elbe River in Germany and Rotterdam in the Netherlands—to ride with other pilots in search of an answer.

“We looked at everything from SWATH (small-waterplane-area twin hull) boats to helicopters to big boats in Europe, and ultimately came to the conclusion that we were going to stay with a large boat operation,” said Ed Burns, marine superintendent for the Staten Island-based pilots group, which provides pilotage services to all foreign flag vessels and American vessels under register entering or departing the Port of New York/New Jersey, the Hudson River, the East River, Atlantic City, Jamaica Bay and Long Island Sound.

The Sandy Hook Pilots use a rotation of two station vessels, New York and New Jersey, that basically serve as offshore hotel offices for the association’s pilots as well as traffic control for the port. The older of their two vessels, the 182-foot New York, entered service in 1972, and is the last large station vessel in the U.S. The boat gained an additional 15 years of service following a repower and refresh in 2004, but the pilots began looking for a replacement as its useful life started to run short.

After determining the $30 million price tag for a potential newbuild would be too steep, the pilots began their next search mission: tracking down a vessel that would be the perfect conversion candidate. “We stumbled across the Maine Responder laid up in Portland, Maine and made the decision that it would probably be a good fit for us,” Burns said.

Old and new: The old New York (left) docked alongside its replacement. (Photo: Sandy Hook Pilots Association)

Old and new: The old New York (left) docked alongside its replacement. (Photo: Sandy Hook Pilots Association)

Asked what made the Maine Responder—a 1993-built oil spill response vessel (OSRV) previously used by Marine Spill Response Corporation (MSRC)—a good fit for pilots operating in and around the busiest port on the U.S. East Coast, Burns said condition was a key consideration, and that the boat had been very well cared for. “The vessel was referred to as a pier queen. It had barely been used—just 9,800 total hours—at the time we bought it,” Burns said. “The interior, the tanks, everything was essentially brand new. We did a pre-purchase survey, and everything checked out; the boat was in great shape. And when we inspected all the internals in dry dock—pulled the shaft, the rudders, everything—all was in fantastic shape.”

In addition, many of the vessel’s characteristics were just right. At 204 feet, the Maine Responder was in the desired size range, and it had the correct engines: the same 3512 CATs that are in the old New York. “We’re not towing with this vessel and we’re not pushing with it; it’s not a tugboat, it doesn’t require a whole lot of horsepower,” Burns said “It’s a more fuel efficient than, say, if we had gotten a 200-foot supply vessel out of the Gulf of Mexico.”

With the right vessel in hand, next began the process to convert it. Mystic, Conn.-based by JMS Naval Architects, which surveyed and helped evaluate the vessel prior to purchase, was tapped to develop the conversion concept design and provide engineering support to the shipyard as well as owner’s representative services during the project.

JMS’ president, Blake Powell, said, “Our initial goal was to assess how well a purpose-built OSRV could meet the mission requirements unique to a pilot station vessel. JMS assisted with this feasibility phase by conducting a survey, providing a seakeeping analysis and defining the scope of modifications.”

And while the Maine Responder was in excellent shape, changing any vessel’s mission presents technical, operational and regulatory implications that can be difficult to balance, Powell said, adding that the integration of new systems with original ones is always a design challenge.

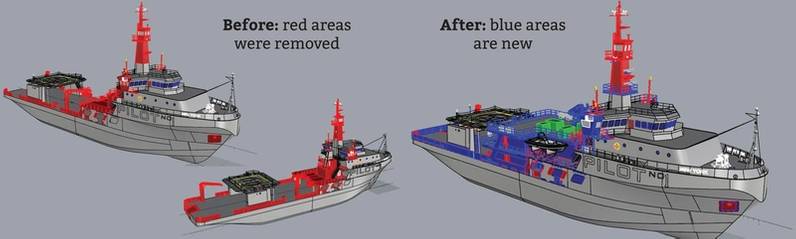

“The major conversion involved removing the oil recovery equipment, modifying tankage and adding a large deck house for the pilot accommodations,” Powell said. “Fortunately, there was very good documentation for a 28-year-old vessel, but our naval architects still spent lots of time crawling every inch of it.”

Burns said that the Sandy Hook Pilots, as a New York business, saw it as a priority to keep as much of the work as possible within the state. “We started the process at Caddell Drydock and Ship Repair in Staten Island, and did a lot of the removals of the oil spill equipment that was installed on the vessel. Then we moved up to Feeney Enterprises in Kingston, N.Y., and they did the fabrication and installation of the new houses. We used Cooley Marine for the interior, they’re out of Connecticut. We were able to do this whole project locally.”

(Image: JMS Naval Architects)

(Image: JMS Naval Architects)

The converted Maine Responder, now renamed New York to replace the previous vessel of the same name, offers a number of significant improvements over its predecessor. “It can hold station for six weeks as opposed to three weeks, so it’ll only have to come in half as often. It has a much larger fuel capacity, much larger potable water capacity. And that was part of our criteria when we sat down with JMS. One of the things we wanted to do was get more time out of the vessel offshore before it would have to come in for shore days,” Burns said.

New potable water tanks with 60,000 gallons capacity were fabricated and installed to help enable the longer stays offshore. Another major addition was the construction of a two-deck house that sleeps up to 28 pilots, with a pilot’s lounge and mess hall. “Although safety was the first priority in the design, the pilots’ comfort while they were onboard was a close second. We conducted a baseline noise survey and specified materials and installation methods intended to make the accommodation spaces as quiet as possible and conducive to the pilots getting quality rest between assignments.”

The bridge wings were also extended to give a clear view of the pilot launch landing area on each side of the vessel with CCTV camera system installed throughout the vessel’s interior and exterior spaces. Powell said other modifications had to be made to incorporate operational capabilities specific to the pilots’ mission, specifically boarding the vessel at sea safely. “The design included modifications to the boarding area, extending the bridge wings for improved visibility, incorporating a heated deck to de-ice the boarding area, a man-overboard rescue system and a means to rapidly launch a rescue boat.”

The result was a port rescue station with net recovery system, deck de-icing systems at port and starboard pilot boarding stations, hot water/steam system for power washing to de-ice the pilot boats when alongside in winter, new knuckle boom crane to service the port and starboard rigid inflatable boats (RIB) and load gear pier side, and small boat fueling/transfer stations port and starboard.

Also added were two-way communication speakers from boarding area to the pilothouse port and starboard bridge wings; buzzer system for communication between the pilothouse and crew mess and the port and starboard boarding areas; floor to ceiling windows facing aft and down for viewing of pilot boarding station; relocating controls to bridge wing, steering, engine, VHF, gyro repeater, bow thruster, new two-way talk back to boarding station; and side windows facing outboard, sliding/opening.

The completed vessel, the new New York, retains its helicopter pad, ABS classification, and U.S. Coast Guard certificate of inspection (COI) as a Subchapter I vessel.

“We’re very happy with the new vessel that we have, and we’re really looking forward to putting it into service and getting many years out of it,” Burns said.

(Photo: Sandy Hook Pilots Association)

(Photo: Sandy Hook Pilots Association)

Read The New 'New York' in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 2022 Marine News

Other stories from April 2022 issue

Content

- Interview: Shane Guidry, Harvey Gulf page: 12

- Maritime Antitrust Immunity in Crosshairs page: 16

- US Offshore Wind: Figuring Out the Business page: 22

- New Routines on the Bridge in the Digital World page: 28

- The New 'New York' page: 34

- Nabrico Unveils New Line of Steel Davit Cranes page: 37

- eMachine: Scania’s New Hybrid Marine Power Solution page: 38