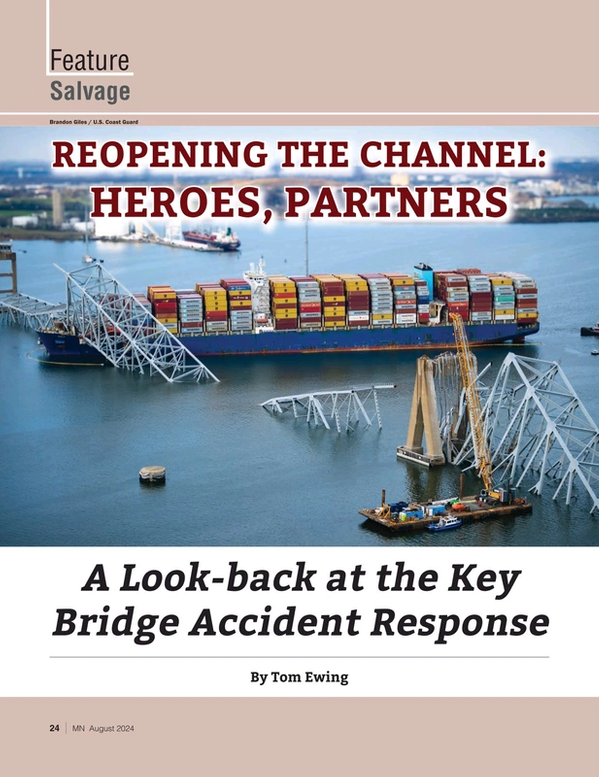

Reopening the Channel: A Look-back at the Key Bridge Accident Response

“The enormity of this disaster is hard to imagine without seeing it in person…It may sound dramatic but given the wreckage field created by the collapsed bridge, the environment divers are working in, and the dangers posed to them, is like cleaning the site of 9/11 with blinders on.” - Rick Benoit, Emergency Management specialist at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) North Atlantic Division (NAD), from USACE news report.

Col. Estee Pinchasin is commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Baltimore District. On Tuesday, March 26, she was awakened by a middle-of-the night call from her mother-in-law with a disquieting message: there was an accident on the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Her mother-in-law added: “I figured you’d have something to do with this.”

An understatement to be sure. Within hours, Pinchasin became one of six Unified Commanders to lead the Unified Command team established by afternoon March 26. The bridge became her life for the next two and a half months.

In an interview, Pinchasin was asked about some of the critical, initial events as well as some of the major decisions and events as the recovery efforts developed. Her initial thought: it happened in the middle of the night! Sadly, the world learned later, six contractors were killed. But at 1:30 a.m. there was no morning rush on I-695. The State Police, responding to a mayday call from the Dali, the containership that struck the bridge, had at least a few minutes to block the roadways, saving countless lives.

Then, Pinchasin said, the phone calls started. Even early reports indicated a major disaster. The 50-foot-deep Fort McHenry channel, under the bridge, is USACE’s jurisdiction, a channel critical for regional, national and international trade, a route supporting thousands of jobs in the Port of Baltimore and the region.

“There was no waiting for someone to call me and say, ‘Okay, this is your assignment,’” Pinchasin recalled. “USACE has maintained this channel for over 100 years. We had to clear it.” Fifty-thousand tons of wreckage crashed into the Patapsco River.

Initial outreach went to USACE’s emergency management teams. The Coast Guard was contacted. “Everybody knew,” Pinchasin recalled, “that the debris was nothing that we were going to be able to handle individually. This task would require collaboration.”

Critically, Pinchasin and her team could draw upon recent and similar teamwork that followed the March 2022 grounding of another large containership, the Ever Forward, near Annapolis.

“We partner with these stakeholders when it's not an emergency,” Pinchasin pointed out. “A human connection already exists among us.” The decision was made to again establish a Unified Command, enjoining six agencies, to oversee Key Bridge recovery. A top executive from each agency became one of six Unified Commanders. As USACE’s top official for the Port of Baltimore, Col. Pinchasin became a Unified Commander (with the Ever Forward incident the USACE was not part of the Unified Command because the vessel was in a state, not a federal, shipping channel).

Importantly, the Army Corps could take advantage of an interagency agreement with the Navy, an agreement that allowed the Navy’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving (SUPSALV) to call the contractors it has on standby, ready to react in just such an emergency situation. For the Key Bridge project, Donjon Marine, based in New Jersey, was on point and, indeed, mustered its team and equipment and moved into action. Pinchasin said Donjon was on site in less than 12 hours.

“Everybody knew that the debris was nothing that we were going to be able to handle individually. This task would require collaboration.” - Col. Estee Pinchasin, Commander, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Baltimore District. (Photo: USACE)

“Everybody knew that the debris was nothing that we were going to be able to handle individually. This task would require collaboration.” - Col. Estee Pinchasin, Commander, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Baltimore District. (Photo: USACE)

Stranded energy

Pinchasin highlighted the deliberate and precise planning required for recovery operations. She noted the potential energy trapped within twisted steel and cables and rebar, energy held in check, tied up really, by being at the bottom of a pile and weighed down further by roadway, water and mud. Moving that debris meant releasing that energy, like a gigantic malevolent clock spring.

“A person quickly realizes how different salvage operations are from construction,” Pinchasin commented. “Salvage work isn’t easily planned out on a Gantt chart. Timing, rates of placement and movements and units of measure are very difficult.” Sometimes the rigging, she said, takes longer than the cutting and lifting. She noted that some loads took two days to lift, moving just inches at a time because the crane operators had to evaluate how each load reacted, how it might shift as ruined sinews snapped free one final time. One USACE news report commented that crane operators and crews need “nerves of steel to operate these metal behemoths from dizzying heights – fighting unpredictable winds and choppy waves below – performing a literal balancing act to shift massive, mud-covered, waterlogged heaps of twisted steel frame and Interstate 695 onto a nearby waiting barge.”

Pinchasin noted the “harsh and unforgiving environment” for the salvage divers who surveyed and delivered the data that the crane team needs to prepare rigging and lifting. Rick Benoit, USACE’s Emergency Management specialist, described the divers’ worksite as “an uber-extreme work environment of dark, cold water. Divers are moving as if playing an underwater game of Twister and Jenga with hundreds of tons of shattered concrete and twisted steel in complete darkness.” Visibility was one or two feet. Divers used survey data from Light Detection and Radar (LiDAR) and advanced sonar imaging to map out underwater routes. They couldn’t stand on the wreckage – it might sink, pulling them into a new trap.

(Photo: Christine Montgomery / U.S. Navy)

(Photo: Christine Montgomery / U.S. Navy)

Leadership, partnership, progress

Another critical factor was the role taken on by the Navy’s SUPSALV team. It’s important to keep in mind that the recovery had three, nominally separate, work zones:

- The USACE and its work to clear the Ft. McHenry channel.

- Work on the Dali to prepare it for resailing, a task headed by Resolve Marine, based in Florida, the Dali’s contracted emergency response company.

- The State of Maryland, and its contractor Skanska, working in areas outside the federal channel.

[At their customer’s request, Resolve said they could not discuss their work by the deadline for this report. Skanska did not reply to inquiries.]

In reality, of course, it was one work zone. And this is where the Navy stepped up – to coordinate contractors’ efforts, to ensure safety, with blasting zones, for example, and coordinating access in order to best synchronize all crews and equipment and schedules.

The Navy’s coordination, Pinchasin said, allowed the three primary contractors to “share resources, and, most importantly, share lessons.” The Navy team, she explained, “enabled each person and salver to get what they needed to do based on their prioritization. Everyone knew of critical activities well in advance and coordinated their schedules.” This teamwork, she said, delivered “incredible capabilities.”

In one Army Corps media report Pinchasin gave a particular shout out to the crane operators and teams. “Their skill, experience and professionalism in removing submerged wreckage is truly unmatched,” Pinchasin said, and added further, “Pulling these massive loads out of the water can be highly unpredictable. The crews must ensure the wreckage is balanced and properly secured to its rigging. It requires a tremendous amount of patience and is as much art as it is skill. To do that, without injury or damage to their equipment, represents a standard of excellence that’s indispensable on this mission.”

It takes a fleet to raise a bridge. (Photo: Donjon Marine)

It takes a fleet to raise a bridge. (Photo: Donjon Marine)

Insomnia. Let’s get to work

John A. Witte, Jr. is president and CEO of Donjon Marine Company, Inc. Over the past 50 years Donjon has become a seasoned, experienced player in maritime emergency response. Donjon participated in the Ever Forward refloating, in recovery efforts after Superstorm Sandy in New York and after Hurricane Katrina in the U.S. Gulf. As noted above, Donjon is the Navy’s emergency responder for the Atlantic zone, and it was the Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Diving that facilitated Donjon’s priority role with the Army Corp.

Witte received a call about the Key Bridge a few hours after the Dali’s hit. His initial thought: “It’s time to go to work.”

Over the last 40 years, Donjon has worked extensively in the Chesapeake Bay. Donjon knows the territory. “We had the advantage of an already developed relationship with the COTP (Captain of the Port),” Witte commented, “and with local regulatory organizations. We had developed a level of trust and mutual respect which, obviously, is always a positive when dealing with any sized event, but especially one of this significance.”

Witte said that in an emergency the most pressing challenge is to establish coordination among players – not easy when people are trying to understand, in the dark, exactly what happened and to what extent. People and safety are the top concerns. “Steel can be replaced, and bridges rebuilt,” Witte commented, “but when a life is lost, there is no way back from that.”

Once at the scene Donjon linked up with Navy, Coast Guard and Army Corps counterparts. An initial site survey allowed the new Unified Command to issue its first instructions. Donjon’s team knew, from the accident dynamics, there was no way to remove intact pieces of the collapsed bridge and highway. He cited an old joke at Donjon: “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. That’s how we started on the wreckage.”

Donjon brought the largest barge crane on the east coast, the Chesapeake 1000, to the Key Bridge site three days after the emergency started. Other assets included a hydraulic wrecking bucket and independent horizontal shear. The 1000 short ton bucket – called “the Grab” – was affixed to the Chesapeake, lowered to where its jaws could closed around debris and then lifted. The horizontal shear partnered with an onsite crane barge, cutting debris that could not be cut manually. New underwater survey capabilities included a system known as "Blue View" – a 3-D scanning Sonar generating a clear and detailed view of debris. Operators could develop lift and removal plans based upon actual conditions, not just estimates. However, once the scope of the work became clear, additional equipment was called in from New York plus Donjon hired numerous local operators to assist. Additionally, some equipment was moved from other projects, and other customers.

“We worked to satisfy our obligations,” Witte said, “but when faced with this national disaster most customers understood and supported our need to move to the Key Bridge site.” Witte was insightful on this give-and-take: “One thing that I have always seen in over 45 years of service to the marine community in times of need, is that we all somehow find a way to put aside petty bickering and our normal financial concerns and work together to fix the problem. This is the United States I know, love and am honored to support in our time of need.”

Finally, Witte was asked: what kept you up at night?

“Marine salvage has made me an insomniac,” he remarked. “I am typically up at night worrying about or planning for something as it relates to Donjon Marine.” But he was confident in his team, that they had the right plan, the right equipment and support of the Unified Command.

Looking back, Witte said the work proceeded smoothly. “There are always hiccups and even occasional missteps,” he commented, “but on this project, with the right people and an environment of cooperation and a common goal, these hiccups were minimal and nothing that impacted overall performance and timing. Donjon was proud to be a part of the emergency response team. The attitude/desire to work together is the most important lesson we take from incident to incident.”

Because of Herculean efforts of hundreds of unnamed heroes, the Ft. McHenry channel reopened its 50-foot depth, 700-foot width on June 10, one day shy of 11 weeks after the crash.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sailfish, an 87-foot Marine Protector class vessel, prepares to escort Dali during its transit from the Port of Baltimore to the Port of Virginia, June 24, 2024. (Photo: Christopher Bokum / U.S. Coast Guard)

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sailfish, an 87-foot Marine Protector class vessel, prepares to escort Dali during its transit from the Port of Baltimore to the Port of Virginia, June 24, 2024. (Photo: Christopher Bokum / U.S. Coast Guard)

Event Timeline: A Summary

- March 26: Dali strikes the 1.6-mile Francis Scott Key Bridge near Baltimore, over the Patapsco River, at about 1:30 a.m.

- March 26: Unified Command is established. It includes the US Coast Guard; The Army Corps of Engineers; Maryland Department of the Environment; Maryland Transportation Authority; Maryland State Police; and Synergy Marine (a private emergency response contractor).

- March 30: Wreckage removal starts

- April 1: The first of two temporary channels is opened

- April 2: The second and deeper temporary channel opens

- May 2: Dali is refloated

- June 10: USACE announces full restoration of the channel

(Photo: Brandon Giles / U.S. Coast Guard)

(Photo: Brandon Giles / U.S. Coast Guard)

Read Reopening the Channel: A Look-back at the Key Bridge Accident Response in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of August 2024 Marine News