ROVs: Time for Renewal in the Work Class world?

There are tentative signs of the start of a renewal in the work class ROV fleet. But what form will it take?

The work class ROV (WCROV) market has taken something of a battering over the past few years. The 2014 downturn and then a pandemic has meant the ROV services market and the fleet have suffered (see panels), alongside the rest of the offshore industry.

Oversupply, thanks to a spate of investment in new vehicles through 2010-2014, and a drop in demand has meant there’s been little appetite for new WCROV investment, says George Shirreffs, VP sales and marketing, Schilling Robotics, TechnipFMC.

In addition, there have been new types of vehicles coming into the market, like the Reach Surveyor and soon also Oceaneering’s Freedom, taking on some of the work WCROVs previously did, such as pipeline survey.

There are now, however, signs of light. For one, activity did recover in the latter half of 2020, says Peter Buchanan, Director Products and Services Subsea Robotics and Tooling (SSR), Oceaneering. In addition, the offshore wind market has been making more use of WCROVs, enabling them to do cable lay survey and cable pull in, for example, with one vehicle, as well as handle the high currents often found in shallow water offshore wind areas, he says.

Oceaneering’s Isurus, launched in 2019, has been making ground in this market, where the likes of heavy lift/cable lay operators have swapped out their vehicles, such as a Millennium for an Isurus, which is specifically configured for high current operations, says Buchanan. For a cable lay operation, the ROV is a pacing item; if it’s slow, it’s holding up the cable lay operations, which can be a $350,000k/day cost, he says.

Shirreffs also sees positivity. “We are starting to see the shoots of the next growth cycle,” he says, which includes interest from renewables. It’s also about time for a new investment cycle, adds Peter MacInnes, TechnipFMC’s marketing director, ROV Services. These occur usually every 10-12 years and are often also linked to technology progression, he says. In the past, that’s been about increasing reliability, depth rating and power, with uptime as a key metric. Now, TechnipFMC is looking instead at productivity, he says, the result of which is their Gemini WCROV, of which it’s operating two in the US Gulf of Mexico. Part of this is about automation. On Gemini, tool acquisition is no longer a manual piloting task, it’s an automated manipulator task, using machine vision and force accommodation, Steve Cohen, Vice President of Product Development at Schilling Robotics in TechnipFMC, told the Underwater Technology Conference, held online in June. Staying subsea longer is also part of it; Gemini has achieved a 28-day dive duration and 120-day capability is on the horizon, he says.

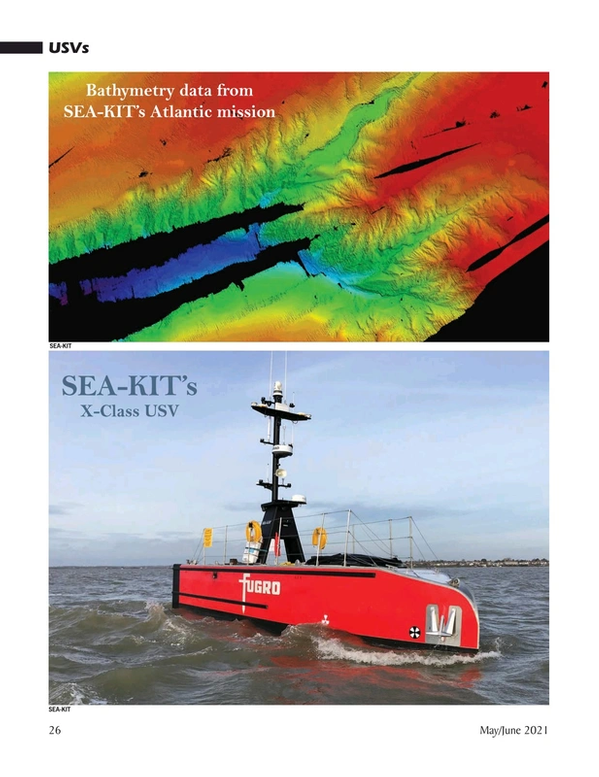

Fugro’s FCV ROV. Photo from Fugro.

Fugro’s FCV ROV. Photo from Fugro.

Automation and remote operations

Oceaneering has Video Tracking and Positioning (VTAP), a form of machine vision technology, to enhance dynamic positioning of its vehicles relative to objects in the field, such as a valve panel, allowing pilot supervised hands hot stab operations, for example. Automation supports another growing area; remote piloting. With more automated tasks, using VTAP, any latency is easier to overcome, says Buchanan, although the 4G networks now available limit latency. Oceaneering has, across all its systems, done 50,000 hours of remote piloting on 3300 operations (including remote survey) using 22 WCROVs, says Buchanan, from remote pilot centres in Morgan City, Stavanger and soon another in Aberdeen. While Oceaneering’s Liberty system (the E-ROV with a cage and battery pack) is 100% remote operated, remote piloting of the rest of the WCROV fleet is a hybrid set-up – onshore pilots supplement offshore ones.

ROV crew will still be needed offshore for some time, to support launch and recovery operations and vehicle configuration and maintenance, he says. But also having onshore pilots lowers how many crew have to be sent offshore, reducing bed space constraints, HSE risk and logistics, and means crew spend less time offshore not doing anything. Also, says Buchanan, specialists can more easily be brought in for specific tasks when they only have to visit an offshore pilot station. “Until the system itself changes fundamentally, it’s still designed to be maintained regularly,” he says.

“For Fugro, the entire strategy is about doing as much as possible remotely and with uncrewed systems,” says Ivar de Josselin de Jong, Director Remote Inspection at Fugro. “Our strategy is that everyone who is only looking at a screen will work from a remote operations centre in the future.” In addition, operating remotely operated vehicle (ROVs) from an uncrewed surface vessel (USV) in an uncrewed environment, makes going all electric “a no brainer”. Fugro has a fleet of ROVs, from smaller systems to its own range of FCV WCROVs, and a network of eight remote operations centres, although WCROVs are not operated from these yet. It’s now adding new electric vehicles to the fleet that will be operated remotely via its new uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), including the Blue Volta and Blue Amp, a new light work class vehicle.

ROV electrification

Electrification of heavy duty WCROVs will come, in time, but will be a challenge, he says, “because of the power requirements and that also has an impact on how far you can go with autonomy and potentially even tetherless operations, because there’s a limited amount of energy.” There will also still be a place for crewed ROV vessels and more traditional systems, when they’re needed. Moving to all electric also has another challenge; the availability of electric tooling, as the market is dominated with hydraulic systems currently.

Others are also developing electric systems – including tooling. SMD unveiled its electric vehicle (EV) WCROV early last year. Saipem is working on the Hydrone W fully electric work class ROV. Saab Seaeye is developing an all-electric full work class ROV (bigger than its Leopard work class ROV, which in large part took over the work of Saab’s Jaguar, because it was smaller and more powerful). Part of this move has been Saab’s development of a T4 equivalent electric manipulator, or e-manip, which is currently being beta-tested by a client in the US (it’s also been trailed on a Sabertooth, although it wasn’t designed for this vehicle).

Going electric does have many benefits, says Buchanan, including lower power consumption and greater reliability. It would also support more hybrid states of operation, where an ROV is left on the seabed, for example, like the Liberty eROV system. Could that even mean being able to release the tether?

For TechnipFMC, the focus is on lowering the cost of ownership and environmental impact, but hydraulic will always still be needed, says MacInnes. While electric can work for survey or mapping, enabling greater propulsion efficiency, maintenance and repair operations still need hydraulic, “because there’s a sea full of subsea production system equipment that requires hydraulic intervention,” he says.

So, the future is more automated and maybe electric, with a greater mix of vehicles out there. Andy Rose, technical advisor at IMCA and a former ROV pilot, says, “I think we’re going to end up with a split, with big WCROVs doing construction and installation jobs and what’s traditionally been the inspection market will go over to AUVs, certainly for all survey.” We’ll be moving away from tethers, using better batteries and get better at sending information and controlling things under water, he says, as a drive to reduce reliance on crewed vessels continues.

Oceaneering’s Isurus ROV, designed for harsh current operations in offshore wind work. Photo courtesy Oceaneering

Oceaneering’s Isurus ROV, designed for harsh current operations in offshore wind work. Photo courtesy Oceaneering

Read ROVs: Time for Renewal in the Work Class world? in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of May 2021 Marine Technology