World Navies Report: Malaysia

Navies operate on a spectrum between deterrence and defense, to include offensive operation, support of foreign policy, and power projection to civil affair and humanitarian assistance and disaster response. Many have constabulary responsibilities, and it could be argued that, with the exception of the largest navies, most are more like a coast guard than a military force in their normal responsibilities.

Every Navy is different. Yes, they all share similar challenges of acquisition, maintenance, manpower, basing, communications, information systems and the usual requirements of a military service, compounded by harsh maritime environment. Each nation and their navy has a different place to operate in, a different nation and resources to protect, and different threats to protect them from.

That’s what makes studying the navies of the world interesting—to see how they have addressed their specific challenges with the resources they have applied to them. Here we look at Malaysia.

In Malaysia, downsizing the number of ship classes is a good thing

Malaysia is also a nation dependent on maritime trade. As that Southeast Asian nation’s maritime traffic grows, so do the threats such as piracy and trans-national criminal terrorist activity. With the navy’s resources stretched thin, maintaining and operating the variety of ship classes from different countries has become unsustainable. As maintenance costs on the older ships become more expensive, their combat capability is becoming degraded. That’s why the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) is rationalizing its fleet from 15 different classes--built by 13 different shipbuilders in seven countries--to five basic types. That means moving away from the larger frigate type ships to small ships, still large enough to meet operational and training requirements and regional commitments, and able to coordinate and collaborate effectively with our partner navies in the region, such as Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Singapore.

The new classes will include 12 littoral combat ships (LCS); 18 littoral mission ships (LMS); 18 patrol vessels (PV); four submarines; and three multi-role support ships (MRSS). The first batch of LCS (six ships), based on the French Gowind OPV, is already in construction in Malaysia. The first four LMS is currently being built in collaboration between Malaysian and Chinese builders. The LMS will be smaller and less capable that the LCS, but will have a modular multi-mission concept suitable for many RMN requirements. The first batch of Kedah-class PVs, based on the German MEKO 100 design, is already in service. The MRSS will serve as the main platform to transport troops and equipment, support humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations, and be able to operate with the ASEAN Military Ready Group (AMRG). Malaysia hopes to do as much of the design and construction itself to enhance the domestic defense industry and become self-reliant and capable of building modern and reliable warships.

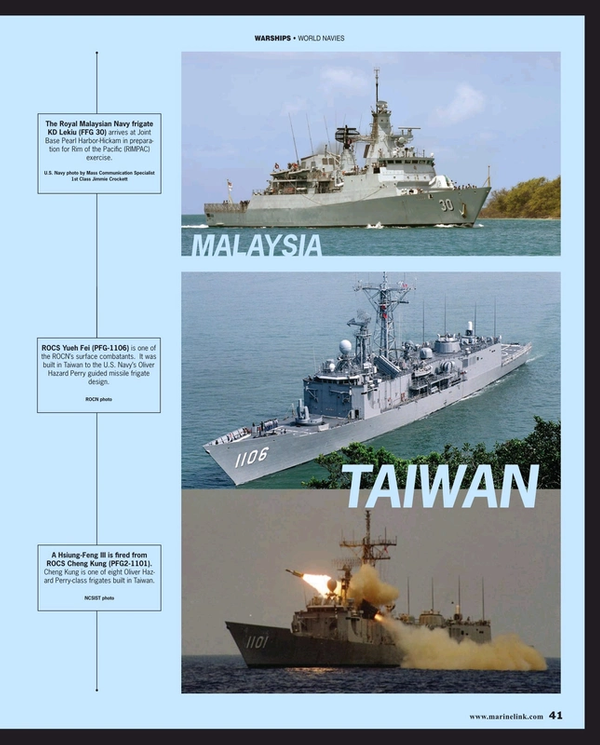

The RMN currently operates two British-built frigates, KD Lekiu and KD Jebat, which are being given a mid-life refit to be kept relevant until the new fleet is in place. Terma SCANTER 6000 radars have been installed on the two Lekiu-class frigates for navigation and helicopter control. The radar will also provide a data feed to the BAE Systems Nautis combat system and will be integrated with the Northrop Grumman Sperry Marine Vision Master automatic radar plotting aid (ARPA) display system. The RMN also selected the SCANTER 6000 for its two new Multi-Purpose Common Support Ships (MPCSS).

Read World Navies Report: Malaysia in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 2019 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from April 2019 issue

Content

- Maritime Fatigue: Just another band aid? page: 10

- OSVs: Restarting that Idled Vessel page: 12

- OSV Market: Which Way is Up? page: 14

- A New York State of Mind page: 20

- Interview: Astrid Skarheim Onsum, SVP, Head of Wind, Aker Solutions page: 24

- Maritime Autonomy: The Reality page: 28

- World Navy Report: Peru page: 38

- World Navies Report: Denmark page: 39

- World Navies Report: Belgium page: 39

- World Navies: Taiwan develops indigenous combat capabilities page: 40

- World Navies Report: Malaysia page: 41

- World Navies: Brazil´s Riachuelo Submarine page: 42

- Design: RNLI’s Shannon Class Lifeboat page: 44

- e-Navigation Passage Planning transformation page: 52