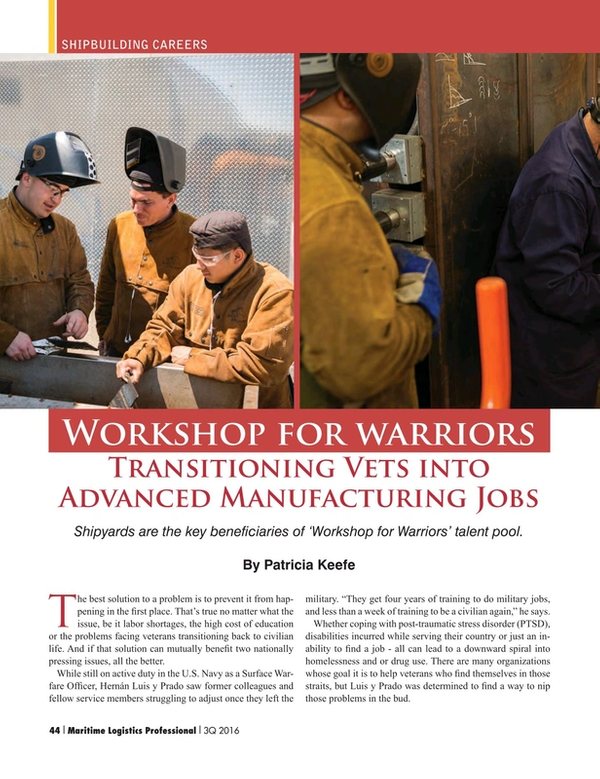

Workshops for Warriors: Transitioning Vets into Advanced Manufacturing Jobs

By Patricia Keefe

Shipyards are the key beneficiaries of ‘Workshops for Warriors’ talent pool.

The best solution to a problem is to prevent it from happening in the first place. That’s true no matter what the issue, be it labor shortages, the high cost of education or the problems facing veterans transitioning back to civilian life. And if that solution can mutually benefit two nationally pressing issues, all the better.

While still on active duty in the U.S. Navy as a Surface Warfare Officer, Hernán Luis y Prado saw former colleagues and fellow service members struggling to adjust once they left the military. “They get four years of training to do military jobs, and less than a week of training to be a civilian again,” he says.

Whether coping with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), disabilities incurred while serving their country or just an inability to find a job - all can lead to a downward spiral into homelessness and or drug use. There are many organizations whose goal it is to help veterans who find themselves in those straits, but Luis y Prado was determined to find a way to nip those problems in the bud.

It struck him that the common thread was unemployment. Former military who failed to land a job could quickly lose their homes, their families and in short order, their confidence and sense of self-worth. Once that was gone, it wouldn’t be long before the bottom fell out. That’s because among Hernán’s students, 68% receive disability benefits, 60% are unemployed or underemployed and 26% are in temporary/insecure housing situations.

Critical Labor Shortage

Luis y Prado, who trained as an engineer, came to realize that there was – and remains – a critical nationwide shortage of workers with advanced manufacturing skills. As many as 2.3 million vacancies out of the 3.5 million jobs that will need to be filled over the next 10 years, according to multiple industry and research sources. “We kept seeing older and older people building and repairing ships and maintaining equipment and saw this was not sustainable.” Among U.S. shipbuilders, for example, welders and fabricators are in especially short supply.

Another brewing problem is that the average age of the current manufacturing workforce runs around 59 to 63, which means at the very moment when American manufacturing is resurging, it faces a huge retirement bubble opening up another estimated 2.7 million positions, which will both deepen the shortfall and wipe out decades of knowledge unless something is done to make sure it gets passed on.

“If we do not prepare a generation of people who can do what needs to be done and train others to do that, America is in peril. This [retirement bubble] is the perfect opportunity to get the million-plus veterans expected to transition over the next five years and get them certified and trained in advanced manufacturing,” urges Luis y Prado. “Vet 2.0 – The next greatest generation!”

“The reality is we need the next generation of skilled craftsmen to come in. Usually 70%- to 90% of the new guys are completely green. Workshops for Warriors is a good thing. [Their graduates] are already ahead of the majority of folks going for similar jobs,” says Matthew Paxton, president, Shipbuilders Council of America.

Coincidentally, veterans who held welding, machinist and fabrication jobs in the military found they lacked the ticket to civilian employment: nationally-recognized credentials. For those veterans whose skills lay in other areas, getting credentialed would be a quicker path to a well-paying job than four- or even two years of debt-inducing college study leading to uncertain employment.

Meanwhile, Luis y Prado, who served 15 years in the U.S. Navy, was shopping at a mall when he ran into a friend from his recent tour in Iraq. He was shocked to find the man had lost both legs, and the thought that all of his friend’s aspirations might not come to pass due to his injuries so greatly affected him, that he says he literally fell to the ground and told his wife Rachel on the spot that they need to sell everything and get to work on helping veterans like his friend. She was in.

Seeing a perfect fit between two problems where each seemed to be the answer to the other, Luis y Prado hit upon the idea of “rebuilding American manufacturing one veteran at a time,” through what became Workshops for Warriors (WFW), a program that funnels veterans desperate for a sustainable career path into an industry desperate for skilled workers.

“From Frontline to Production Line”

“We are building an army that will get America back on track as the world’s advanced manufacturing superpower,” promises Luis y Prado. “We’re teaching a new way of manufacturing; our graduates can do what used to take three to four skilled tradesmen. The Secretary of the Navy calls us the ‘Seal team of manufacturing.’ ”

WFW is today a state-licensed, board-governed, 501 (c) (3) nonprofit school, laser-focused on providing veterans, wounded warriors and transitioning military personnel with accelerated training in advanced manufacturing skills and the opportunity to earn up to 62 industry-recognized, portable, stackable credentials required for careers in welding, machining and fabrication - at no cost to the students. The school targets 18- to 24-year-olds.

The program offers two training tracks – welding/fabrication, accredited by the American Welding Association, and advanced machining, accredited by the National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS). Unlike traditional apprentice programs, where participants might weld a few hours a day over the course of a year-long program, WFW students spent most of their eight-hour day “welding, welding” using $6 million worth of donated, state-of-the-art equipment, says Todd Elden, West Coast manager for the Weapons Support Group, BAE Systems and a 26-year Navy veteran.

Students can take a four-, eight-, 12- or 16-month program. Four months of classes and a single credential will provide entry-level, full-time work at $15 an hour. At the other end of the spectrum, the full 16-month program opens up entry-level jobs at $25 an hour.

To date, WFW has graduated 288, who collectively have earned over 1,000 credentials, and have an average starting salary of $60,000. With 2500 job openings just in San Diego for every graduate, the program boasts 100% employment. It has a waiting list of 550 applicants. Its success has garnered a number of awards, and even attracted the attention of the White House, which in 2013, recognized Luis y Prado with its Champion of Change Award, to honor his dedication to helping fellow veterans.

Where the Boys Are

In 2013, Rachael, who is WFW’s COO, told her husband that if he really wanted to make the then five-year-old program a success, he needed to devote full time to it. So he exited the navy, returning to civilian life with a clear idea of what he wanted to accomplish. He settled on San Diego as WFW’s new home. It has not only the largest concentration of military bases, defense contractors and shipyards in the country, but also the largest number – 40,000 – of transitioning service personnel annually.

Next up was finding funding and donors to provide software and training equipment, and scholarships for his students. Although accredited, WFW receives no federal or state money, and students can’t apply the GI Bill to the program until 2018. All funding comes from private donors, big organizations and WFW Industries, a for-profit advanced manufacturing sister facility launched in 2009 that does prototypes, parts fabrication and repair to help support WFW training financially.

“We need the maritime industry to come together and recognize the need to fund this training.” says Luis y Prado. “The only thing constraining us is money.” Industry support and partnerships are especially needed now that the White House has asked Luis y Prado to expand the program to 103 centers around the country over the next five years. But first, Workshops for Warriors is launching a $15 million capital campaign to expand its current location and build a modern, 45,000-square ft. advanced manufacturing training facility in San Diego. The bigger facility with multiple training centers will support at least 750 graduates per year.

A Literal Life Saver

Veterans are lining up around the block to get into the school, which does not advertise or recruit. “It’s all word of mouth,” says Luis Y Prado. And the words being used are “hope,” “future,” and life-saving.

For students also struggling with post-traumatic stress, missing limbs and other debilitating injuries, family breakups and homelessness, the school is the lifeline Hernán envisioned it to be. That’s because WFW provides a safe, familiar environment where instructors and classmates understand the stresses of transitioning, and the value of a military culture.

“Anyone can get certification from an instructor, but can they help you deal with personal stuff you are going through while going to school?,” asks Elden.

“I truly mean it when I say Hernán and this program saved my life,” says student Ryan Palmer, 25, a former Navy hospital corpsman. After anxiety, depression and PTSD forced him to drop out of college, he found his military training had no civilian applicability. After reaching a point in 2015 where he felt “lost and hopeless,” he attended a talk on WFW and ended up moving to San Diego from Michigan to enroll. Seven months and at least five certifications later, he already has a job offer which will return him to Michigan. “This program completely changed my life, and gave me a chance at a real future. Without [it] . . . I don’t know where I would be today or even if I would still be,” says Palmer, echoing classmates when he adds, “This is more than a school, it’s an opportunity for a future.”

Another student arrived essentially homeless, with dependency issues and having lost custody of her children. She described coming to the school as the “first time I found hope.” After 16 weeks of training, she was able to get a job at a good wage, secure housing and is now living with her family again. For Luis y Prado, it is one of his more moving success stories. “If that’s not impact, then why are we doing this? People know if they stick it out, they will have a passport for financial freedom for the rest of their lives.”

“There is nothing like going to one of these graduations and feeling the appreciation of these students. Some live in cars just to be able to be there to do the classes. They get teary-eyed because they know they had nothing to look forward to,” says Rick Biben, president of Gibbs & Cox, Inc., who is on two WFW boards. With 2,500 openings in the area per graduate, “over 90% are hired before they graduate,” he adds.

A Hero’s Welcome on the Shop Floor

You don’t have to ask employers like NASSCO, GD BAE and Vortex Engineering twice to hire a vet. “Students out of high school are looking for a first job. These [veterans] have experience, training, maturity. As an employer, I’ll take that any day of the week,” says Biben.

Beyond patriotic sentiments, there are many reasons why ex-military would be in high demand for advanced manufacturing positions, say BAE’s Elden and Kevin Mooney, another Navy veteran and vice president of programs and supply chain management, NASSCO. Both are WFW supporters.

“These people have succeeded in a difficult environment – the military – and have more discipline and leadership capabilities. They know their way around a ship, all the terminology, how to deal with the customer, how they think. We could not run NASSCO without hiring former military,” says Mooney.

“It is extremely difficult in San Diego to find someone who can machine or weld, never mind both,” says BAE’s Elden, who says shipyards and defense contractors often have to tell the government that they will have to delay work processes or repairs because they don’t have certified welders.

BAE subcontracts work to WFW Industries, and sent two workers through the program, effectively paying for an entire class, in part to “help keep the doors open” in the school’s early days in San Diego. Beyond that, says Eldon, “We do $100,000 worth of work a year through the profit side.”

“When you hire a veteran that’s gone through his system, you get someone who steps on the property ready to go to work, comes with the certifications that you need, and who has that level of dedication to the trade that you need for them and your business to be successful,” Elden notes.

Unlike high school-aged apprentices or vocational or college graduates, most veterans are older, used to problem-solving, committed to what is a physically demanding career path, and in some cases, come with years of experience working as welders, machinists and fabricators on ships. They know where the piece they are making is going, and they know how key precision work is, says Michael Bice, president of Vortex Engineering, because they know what it’s like to have to daily use a poorly made locker or desk, etc..

“They have the ability to learn and improve,” says Bice, explaining that “you spend the whole time in the military training to get better.” For example, a welder he hired from WFW had an ‘okay’ skill level, but his “real value,” says Bice, was his willingness to listen to the more experienced workers on the shop floor helping him grow as a skilled craftsman.

“It takes all those years of knowledge to be passed on from one person to the next to actually be the best at what you do. If we could get young America working side-by- side and transfer that knowledge, it would be most beneficial. I am worried about that gap; every year we delay, it makes it harder,” says Elden.

The fly in the ointment is that WFW can’t graduate enough workers fast enough to meet demand – from students or employers. It’s why Eden thinks the maritime industry should provide a certain amount of tax-deductible financial aid to WFW, who can turn out more skilled workers at a lower cost than apprenticeship programs and give the supporting companies first access to job interviews.

The best thing, though, says Elden, is what the program does for the students. “Early in the program he sent me pictures of students – two were in wheelchairs with no legs, one was missing an arm. These people that have given so much to the country, graduated and were placed in jobs, but without Hernán, they’d be lost. I don’t know how you put a price on that. It’s life changing. It’s why I stay involved.” And it’s why Workshops For Warriors hopes you will too.

Workshops for Warriors: at a Glance

- Mission: To provide veterans with a lifelong career by providing free training, certification and placement in advanced manufacturing jobs.

- Organization: Begun in 2008, Formally launched in 2011 in San Diego.

- Annual Budget: $2.4 million.

- Future Plans: Expand to 103 facilities located nationwide near areas of concentration of military treatment facilities, advanced manufacturing and veterans. 70 sites mapped out.

- Student Demographics: 87% U.S Navy and Marine Corps veterans

- By The Numbers: Wait list of 550, 55 students per 16-week semester, 288 graduates

- Turnover: Over 1,000 credentials earned, 100% employment.

- Costs: Free classes cost $12,000 per student.

- Courses: Machining, Welding, Fabrication, CAD; 62 possible NIMS certifications.

- Funding: 501 (c) (3) nonprofit. Corporate and private donations and grants

- Federal Dollars: Not eligible for government monies until 2018.

- Funding Spent on Training: 87%

- Capital Funding Campaign: To raise $15 million to build a state-of-the-art, 45,000-square ft. advanced manufacturing training facility in San Diego.

- Top Employers: SpaceX, U.S. Navy, UTC Aerospace Systems, Reliance Steel & Aluminum, Pacific Coast Iron and CUBIC.

- For Profit Arm: WFW Industries, to be renamed Vet Powered, provides advanced manufacturing services – all profits go to the school.

The Author

Patricia Keefe is a veteran journalist, editor and commentator who writes about technology, business and maritime topics.

(As published in the Q3 2016 edition of Maritime Logistics Professional)

Read Workshops for Warriors: Transitioning Vets into Advanced Manufacturing Jobs in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of Q3 2016 Maritime Logistics Professional

Other stories from Q3 2016 issue

Content

- USCG Drug and Alcohol Regs: Pitfalls for Foreign and US Carriers page: 10

- Insights: USCG Can Suspend and Revoke Merchant Mariner Credentials page: 12

- The New Voice of the Bulk Terminal Operator page: 26

- Is OCEMA’s Terminal Weighing Approach SOLAS VGM Compliant? page: 30

- The Logistics of Regulating the Supply Chain page: 34

- Goal Zero: An Up-close Look at Shell's Safety Culture page: 38

- Workshops for Warriors: Transitioning Vets into Advanced Manufacturing Jobs page: 44

- US Boatbuilding: Exports Buoy Bottom Lines page: 50

- Risk Management and the Human Element page: 55

- Navigational Question in the Digital Age page: 59