Floating Production Systems: A Big Opportunity for Shipyards

Opportunities for Shipbuilders and Repair Yards In a Huge & Growing Market

Since the beginning of this year, orders have been placed for 17 floating production systems. The combined value of the fabrication contracts exceeds $16 billion. By year end there will likely be another five to eight contracts awarded and the overall contract value for the year will exceed $20 billion.

Stated in terms of conventional ships, fabrication of floating production systems in 2013 will equate to orders for 220 VLCCs, 360 Suezmax tankers or 800 Panamax bulk carriers. In other words, it is a big market. Yet relatively few shipbuilders are active in this sector.

This article highlights the opportunities that non-players are missing and suggests some options for positioning in this market space.

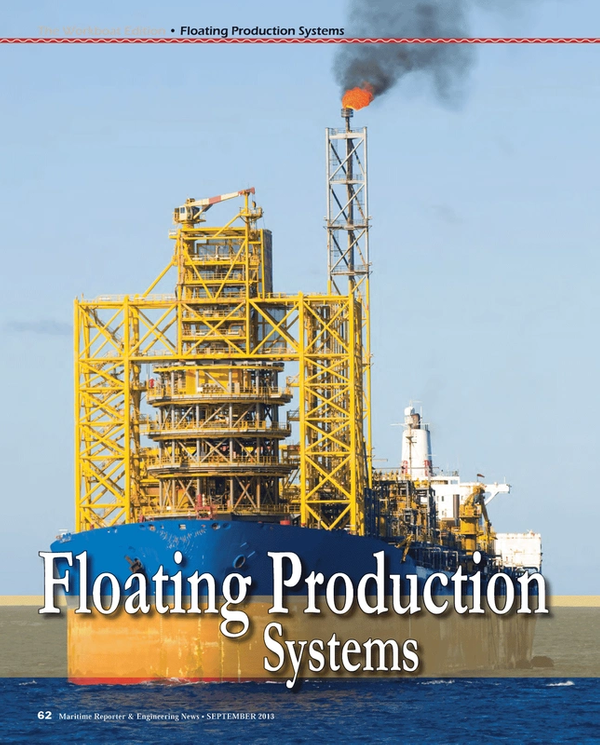

Floating production systems inventory – 269 floating production units are now in service or available. FPSOs account for 61% of the existing systems. The balance is comprised of production semis, tension leg platforms, production spars, production barges and floating regasification/storage units. Another 93 floating storage/offloading units (without production capability) are in service.

The number of production floaters has been growing steadily – there are 22% more units than five years ago, almost 80% more than 10 years back. Including units that have been scrapped, almost 300 floating production units have been delivered since the mid-1970s when floating production began.

Current order backlog – 72 production floaters are now on order, consisting of 40 FPSOs, six production semis, five TLPs, four spars, one barge, four FLNGs and 12 FSRUs. Delivery of the equipment will grow the production floater inventory by 27%.

In the backlog are 46 units utilizing purpose-built hulls, 26 units based on converted tanker hulls and 1 unit being modified from an existing production semi Of the production floaters being built, 41 are owned by field operators, 31 are being supplied by leasing contractors.

Brazil continues to dominate orders for production floaters – 23 units are being built for use offshore Brazil, 32% of the order backlog.

Future demand – Floating production is still in the exponential phase of growth and underlying industry demand drivers are very strong. Key signs – oil prices, planned projects, drilling activity – point to accelerating requirements for new floating production systems over the next five to ten years.

Spot oil prices have hovered in an $80 to $120 per barrel range over the past year and futures pricing is indicating $80 to $100 per barrel through the decade. This pricing environment supports investment in all but the most marginal deepwater developments. At these prices, a floating production system producing an average of 70,000 b/d over the next five years will generate $10 to 12 billion in revenue. After royalties and operating expenses, a $2 to 3 billion investment in the production floater and subsea field development looks pretty attractive.

The portfolio of new floating production projects under study or planned worldwide keeps increasing. As of July there were 241 new floater projects in the bidding, design or planning stage. These are declared discoveries that likely require a production floater for development. A year ago 233 projects were in the planning, design or bidding stage. Five years ago, the figure was 141 projects. Ten years back, 94 projects.

The number and utilization of deepwater drill rigs points to accelerating demand for new floating production systems. Deepwater drill contractors are now operating at full utilization and demand for deepwater drill equipment has driven day rates for drillships and deepwater drill rigs to a record level.

More than 90 additional drillships/semis are scheduled for delivery over next few years. These new drill units will increase deepwater drill capability by 30%, removing a bottleneck that has constrained exploration and development in deepwater. More drill rigs enable more exploratory drilling. Exploratory drilling leads to finds. Finds lead to development decisions. Development produces orders for production equipment.

Given these underlying drivers, over the next five years we expect orders for around 160 production floaters. But the number of orders could be as high as 190 units or as low as 125 units – depending on the price of oil, growth of alternative supply sources and other future macroeconomic developments. In the most likely order forecast, the total value of construction contracts will be in the area of $135 billion. (Exhibit 1)

Competitive landscape

A relatively small number of yards have developed a position in this sector. Presently around 40 facilities are involved in major contracts to fabricate production floater hulls or topsides. They are primarily located in Korea, Singapore, China and (recently) Brazil – with a few others elsewhere in Asia, Europe and North America. (Exhibit 2)

Korean yards Samsung, DSME and Hyundai are the major players in turnkey contracts to fabricate large, complex FPSOs and production semis. For example, Samsung recently signed a $3.1 billion contract with Total to supply a large FPSO for use offshore Nigeria. DSME has a $2 billion contract from Inpex to build a condensate FPSO for use offshore Australia. Hyundai recently signed a $1.9 billion contract with Chevron to supply a large FPSO for use offshore the Shetland Islands.

Singapore yards Keppel, Jurong, Sembawang are major players in converting existing tankers to FPSOs and FSOs. For example, Keppel has a contract with SBM to convert a Suezmax-size tanker to an FPSO for lease to Shell for use in the Gulf of Mexico, a $1 billion project. Jurong just delivered a $0.8 billion FPSO conversion to Modec for use by OGX offshore Brazil. Sembawang has an EPCCI contract from ExxonMobil to convert a VLCC to a $0.3 billion FSO for use in Indonesia.

Chinese yards CSSC, COSCO and CSIC are big players in building or converting hulls to be used as FPSOs. For example, CSSC Chengxi was recently contracted by SBM to convert two VLCC hulls for subsequent outfitting in a local Brazilian facility as FPSOs for use offshore Brazil.

COSCO Dalian has contracts from Modec to convert two VLCC hulls for subsequent outfitting as FPSOs at a local Brazilian facility.

CSIC Dalian has a contract from CNOOC to build an FPSO for use on a field in the South China Sea.

Brazilian yards, some still in the formative stage, have recently emerged as major players in the FPSO fabrication business. They are all focused on the local market. Ecovix is building eight FPSO hulls at Rio Grande Sul for use by Petrobras.

A consortium formed by Odebrecht is converting four VLCCs to FPSOs in Inhauma shipyard (ex-Ishibras), also for use by Petrobras. A third yard, UCN Acu, which is not finished, was to convert two VLCCs to FPSOs for OGX and integrate two other FPSOs for Petrobras. This plan has been disrupted by financial turmoil in OGX. Other facilities such as Brasfels, Quip, Brasa and Maua are involved in final integration of production floaters.

In other areas, MMHE/Technip in Johor (Malaysia) is building a large TLP for Shell for use offshore Malaysia. Paenal, a new yard in Porto Aboim (Angola), is contracted to finish topsides work on two FPSOs being built for offshore Angola. Technip is fabricating a production spar hull for Anadarko at its facility in Pori (Finland). In the U.S., Kiewit and GIFI have contracts to fabricate and integrate topsides for several production floaters destined for the Gulf of Mexico.

Is there space for others? – Absolutely. The floating production sector is still in the early stages of development, the pace of orders for new equipment is growing, production floater technology continues to evolve and cost pressures in Korea, Singapore, China, etc. will impact future pricing competitiveness of many current players. There will be many future opportunities to position in this market space.

Here’s a few positioning possibilities:

• Hull construction

Around 50% of FPSOs and 20% of FSOs utilize purpose built new hulls. Shipyards with Suezmax and VLCC building berths can target positioning in this market. Typical FPSO/FSO new hulls cost $100 to 150 million, but can be as much as $450 million depending on size and owner specification. While stringent offshore service standards apply to the hull construction, the work scope is limited to completion of the hull. Topside fabrication and integration is under separate contract(s) and when finished, the hull is towed to another facility for completion.

• FPSO/FSO conversion

The balance of FPSOs and FSOs are conversions of trading tankers. Ship repair yards with drydocking capability for extended conversion of large tankers can target this conversion business. Of course, there are entry issues. The quality standards for FPSO conversion are more demanding than typical commercial ship repair and upgrade – and the scope of work can be much more complex, as the yard will typically be responsible for the entire conversion project. But this is a growth market that could interest ship repair yards looking for new markets.

• Module fabrication – An FPSO topsides is an assembly of prefabricated modules that house process plant equipment, power systems, accommodation facilities, etc. Each module is designed and engineered to be lifted and readily installed on the FPSO topside. Complex, large FPSOs can involve 15 to 20 modules in total weighing as much as 15,000 tons. Module fabrication could be an interesting market opportunity for yards that have substantial space for steel assembly and can work to stringent tolerances and offshore standards.

• New product development

Leapfrogging existing technology is another entry path. Recently, for example, we advised an investor on the feasibility of building standardized barge-mounted regas plants that would be leased to small power consumers as part of a network of LNG reception facilities. A shipyard could align with an engineering partner and leasing contractor to develop and offer such a product line of standardized regas barges.

The customer would be utilities and power plants on islands and in areas that lack pipeline access. But this is only an example. There are many other possibilities for leveraging product development to enter this market sector.

But there are barriers to entry.

They include

(1) requirements for local content and/or local partner participation,

(2) experience with standards, rules and codes unique to offshore production units and

(3) frame agreements and established customer/supplier relationships that exclude new entrants.

This is also a very conservative industry in terms of accepting unproven suppliers who have no record of production floater performance.

Ultimately the question is whether this market can produce an attractive return on investment. In our view, we think it can be very attractive. It is a huge market involving big ticket purchases that shows no indication of slowing. And current competitors are likely not as entrenched as they might appear. Their costs are growing and the market is continuously evolving.

We think shipbuilders and repair yards not now in this sector should look into opportunities in the floating production market space.

Exhibit 1

Forecast of Floating Production System Orders

Over the Next Five Years – 2013 to 2018

FPSOs – Orders for 90 to 130 FPSOs are forecast, with the most likely being 110 orders. Around 60 percent of orders will be placed by leasing contractors, 40 percent by field operators. Modification and redeployment of existing FPSOs will satisfy around 20 percent of future FPSO requirements. Construction contract value, assuming the most likely FPSO forecast, is estimated in the area of $75 billion

Production semis – Orders for 8 to 11 production semis are expected. The most likely forecast is 9 orders. All will be purpose-built hulls. Most will be directly ordered by field operators, a few will be ordered by leasing contractors or midstream companies. Construction contract value is estimated in the area of $12 billion.

Production spars – Orders for 5 to 10 spars are expected. The most likely forecast is 8 orders. All will be purpose-built. Most will be directly ordered by field operators, a few will be ordered by midstream companies. Construction contract value is estimated around $7 billion.

TLPs – Orders for 4 to 6 TLPs are expected, with the most likely forecast being 5 orders. All will be purpose-built. Most, if not all, will be directly ordered by field operators. Construction contract value is estimated to be in the area of $6 billion.

FLNGs – Orders for 2 to 10 FLNGs are possible. Most likely forecast is 8 orders. The wide forecast range reflects technical and commercial issues still to be resolved. Construction cost is likely in the range of $25 billion, but could be much higher or lower.

FSRUs – Orders for 15 to 23 FSRUs are likely. The most likely forecast is 20 orders. This is a rapidly expanding market sector. Construction cost is estimated in the area of $5 billion, but could be much higher.

FSOs – Orders for 25 to 35 FSOs are expected, with the most likely forecast being 30 orders. Around 33 percent will be purpose-built units. The remainder will be based on converted tanker hulls. Total construction cost is estimated around $4 billion.

Source: IMA

Terms Used:

FPSO – Floating Production, Storage and Offloading Vessel

FSO – Floating Storage and Offloading Vessel (no production plant)

FSRU – Floating LNG Storage and Regasification Unit

FLNG – Floating Liquefied Natural Gas Plant

EPC – Engineering, Procurement and Construction Contract

TLP – Tension Leg Platform

About IMA & Jim McCaul

IMA provides market analysis and strategic planning advice to companies in the marine and offshore sectors. Over the past 40 years we have performed more than 350 business consulting assignments for 170+ clients in 40+ countries. Advising clients on market positioning strategy in the offshore sector is one of our specialties. We have assisted numerous shipbuilders, ship repair yards and equipment manufacturers in formulating a strategy and structuring a plan of action to penetrate the offshore market.

We have worked at all levels of the offshore supply chain. Our assignments have included advice on acquiring an FPSO contractor, forming an alliance to bid for large FPSO contracts, satisfying local content requirements and targeting unmet requirements through technology development.

For further information contact

Jim McCaul at:

Tel: 1 202 333 8501

Email: [email protected]

www.imastudies.com

(As published in the September 2013 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - www.marinelink.com)

Read Floating Production Systems: A Big Opportunity for Shipyards in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of September 2013 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from September 2013 issue

Content

- Shale Oil Is it a Threat to Future Deepwater Development? page: 12

- ZF Marine Propulsion Systems page: 14

- Interview: MAN Diesel & Turbo Head of R&D, Søren H. Jensen, page: 18

- Efforts continue to improve the Modeling of Thrusters page: 24

- GPS Spoofing and the Potential Perils to Ships at Sea page: 26

- Mitigation of Shock & Vibration on Fast Boats page: 30

- LNG Capital Expenditure page: 34

- Safety in Numbers page: 38

- Poland’s Maritime U. page: 40

- Back to School page: 48

- Pick Me Up page: 52

- Liebherr Wins Significant Ship Crane Order page: 54

- BAE Yards Busy with PSV Newbuilds, Ship Repairs page: 58

- The Ties that Bind page: 60

- Floating Production Systems: A Big Opportunity for Shipyards page: 62

- Kirby Corp. CEO Joe Pyne is "No Ordinary Joe" page: 68

- Bollinger Builds page: 78

- Conrad Shipyard: Strength in Diversity page: 82

- SCANIA Powers Ahead in Workboat Market page: 84

- MAN Diesel & Turbo and the Tier-III Age page: 86

- Offshore Service Vessels page: 94

- W&O Expands Repertoire page: 98

- Tech Profile: Colfax CM-1000 page: 102

- A “Look Under the Hood” page: 106

- Beier Radio page: 108

- Carnival to Develop New Emission Reduction Tech page: 110

- Fire Protection for LNG-fueled Ships page: 118

- A Shipyard First Bug-O System’s Heavy-Duty MDS and Hardcoat Anodized Rail page: 120