No More ‘Tug Dilemma’

An ABB-chartered cable-layer ordered in September 2015 might be the only hybrid battery-powered offshore service vessel (OSV) in anyone’s new-build program right now, but don’t say that to the ABB man who led the team that designed the radical electrical system, Onboard DC Grid. The new cable-layer design is the first OSV since the Dina Star to boast a new DC Grid, but in the coming months, “There could be several more,” said ABB Global Product Manager, Johan Olav Lindtjorn. Some of those designs will eventually be tugs.

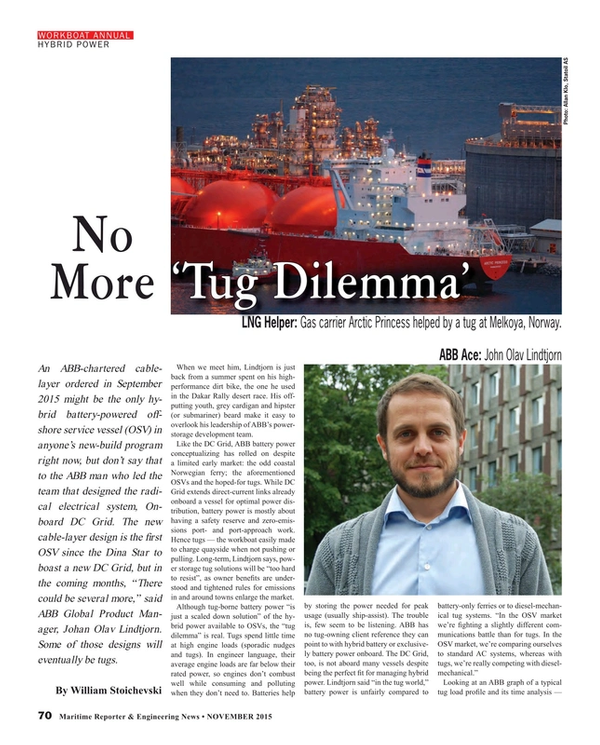

When we meet him, Lindtjorn is just back from a summer spent on his high-performance dirt bike, the one he used in the Dakar Rally desert race. His off-putting youth, grey cardigan and hipster (or submariner) beard make it easy to overlook his leadership of ABB’s power-storage development team.

Like the DC Grid, ABB battery power conceptualizing has rolled on despite a limited early market: the odd coastal Norwegian ferry; the aforementioned OSVs and the hoped-for tugs. While DC Grid extends direct-current links already onboard a vessel for optimal power distribution, battery power is mostly about having a safety reserve and zero-emissions port- and port-approach work. Hence tugs — the workboat easily made to charge quayside when not pushing or pulling. Long-term, Lindtjorn says, power storage tug solutions will be “too hard to resist”, as owner benefits are understood and tightened rules for emissions in and around towns enlarge the market.

Although tug-borne battery power “is just a scaled down solution” of the hybrid power available to OSVs, the “tug dilemma” is real. Tugs spend little time at high engine loads (sporadic nudges and tugs). In engineer language, their average engine loads are far below their rated power, so engines don’t combust well while consuming and polluting when they don’t need to. Batteries help by storing the power needed for peak usage (usually ship-assist). The trouble is, few seem to be listening. ABB has no tug-owning client reference they can point to with hybrid battery or exclusively battery power onboard. The DC Grid, too, is not aboard many vessels despite being the perfect fit for managing hybrid power. Lindtjorn said “in the tug world,” battery power is unfairly compared to battery-only ferries or to diesel-mechanical tug systems. “In the OSV market we’re fighting a slightly different communications battle than for tugs. In the OSV market, we’re comparing ourselves to standard AC systems, whereas with tugs, we’re really competing with diesel-mechanical.”

Looking at an ABB graph of a typical tug load profile and its time analysis — at really low loads 70 percent of the time — and seeing how little time it spends doing high-load ship-assist, Lindtjorn’s frustration simmers.

“It’s ludicrous to be dimensioning your engine for this (tiny need for) full power, when you could have other energy sources cover that peak load for short periods in a more efficient way.”

Telling Tests

It isn’t just commentary. He’s relaying the results of tests at a lab in Trondheim, where cooperation between ABB and Marintek — the electrical and control expertise of the one, the engine knowhow of the other — produced system analysis that included emissions tests mirroring tug operations.

Connecting generator to rectifier and (a motor), they simulated load profiles. They connected a battery (up against a supercapacitor at the other end of a switchable circuit). The super-capacitors — good for repetitive, high-power use — proved not to have the flexibility of the battery. “We’ve seen that the battery is the go-to solution if you have slightly longer durations of any type, where you need a little extra energy,” Lindtjorn says of having the battery in standby mode. In other tests, the battery is given the peak shaving and power-enhancement role in support of the motor, and then, finally, the engine is deliberately tripped (because in reality it’s often at fault).

Measurements clearly showed that with the battery turned off, variable speed operation puts the full load on a generator. Translation: pricy gen-set maintenance. When on, the battery takes the full change in load (instead). It means designers can choose smaller gen sets of fewer cylinders and less output. For owners, it means extra space and a cheaper vessel. In all-electric hybrid systems, mechanical power from the engines converts to electrical current for propulsion and other onboard consumers. “So the generator now operates at a constant load, and the stable pressures and heat mean that everything in your engine works better. The battery doesn’t mind (sharing the load),” says Lindtjorn, explaining that battery power on an AC system forces the use of more electric (transformers) and electronic hardware. “A DC grid solution is more streamlined for energy storage,” he says, although this writer knows AC proponents in shipping hotbed Aalesund who say DC interferes with certain ship operations.

“Dilemma” Solved

“Basically, the tug dilemma is that you have a need for peak power but only for a limited duration. So what do you do,” asks Lindtjorn rhetorically.

In the all-electric ABB tug-power and propulsion model, propulsion is controlled via variable frequency (speed) drives, or VFD. Engine speeds are independent of propulsion, so the engine can be regulated based on load rather than propeller speed. “With diesel-mechanical systems, you’re really required to dimension your engine to meet that (peak) power. You can’t say I only need it a fraction of the time, and so I’m not going to (put in a large engine),” he adds. With the number of zero-emissions harbors set to grow on MARPOL rules, the temptation, Lindtjorn says, is to address the challenge — at least for larger engines — with a different shaft generator and multiple-engine configuration, in which case, “You’re still left wanting a little. You’re still required to have multiple engines.”

“Now have your engines running on variable speed and making their energy available to the DC system, so you can lose one engine and still use two propellers, rather than having to turn on two engines every time you start up the boat,” he explains. The DC system makes energy storage available to all parts of the system, so power can be focused on propulsion rather than your AC needs.

“You can go all-electric, turn off all your engines and still have full functionality. With diesel mechanical you need to think of your minimum speed. That draws a fair amount of power from your engine, unlike an electrically driven motor driven by a converter.”

All that appears to stand in the way of buying an all-electric tug is the availability of charging infrastructure. The exhausting process of choosing a battery type has already been endured by Lindtjorn and his teams in Finland, Norway and Singapore.

Only the Start

Although batteries are no longer investments requiring a national budget, they do come in a bewildering variety of types. Some are better at peak power buy cost more on a kilowatt-hour basis. You need the right one. “With (hybrid electric) tug, the big battery gets you near the ship and starts the operation, and then you have engines running. When you move back to quayside, you’re operating on only batteries and you can do a bit of charging,” Lindtjorn says of “Scenario A” which, back at the lab, offers about 25 percent energy savings. In “Scenario B”, the battery is just big enough to assist the engines, taking the load at low loads and on standby. “B” offers 38 percent energy savings. “You don’t have to have a huge diesel engine that’s only really been put to proper use for 10 percent of its working life, and not even that.”

Lindtjorn says ABB is “all-in” when it comes to developing battery power and is working with yards, charterers, owners and designers to “demystify” batteries and DC Grid. While DNV GL has accepted that peak power can be covered by a battery, it is understood to want one hour of (peak-power) coverage (if not for tugs). Class have approved a tug’s Bollard pull by battery, so the game is on.

“We’re only at the beginning of our understanding of the impact of energy storage on vessels,” the Dakar Rally driver says.

(As published in the November 2015 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)

Read No More ‘Tug Dilemma’ in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of November 2015 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from November 2015 issue

Content

- Interview: Mike Petters - President & CEO, HII page: 10

- Deepwater Downturn: Bump in the Road or Long-Term Slowing of Growth? page: 14

- Out of the Eye ... & Staying There page: 18

- The Latest on Ballast Water Mismanagement page: 22

- Ballast Water Management in the Field Put to the Test page: 24

- When Conducting Investigations Consider 'Privileges' page: 28

- When Using CFD Simulations, an Analysis of Anti-Roll Tanks (ARTS) page: 32

- Opportunities for Growth as Chinese Economy Evolves page: 34

- Big IT: How Fast, How Far Will IT Drive Maritime? page: 38

- The Digital Oilfield Microwave Communication Offshore Brazil page: 42

- Damen’s Norway Foray page: 48

- Thrustmaster Quick Release: Z-Drives with Mechanical Fuses page: 65

- Fourth & Fifth Z-drive Towboat from Master Marine page: 66

- Sneed Delivers Z-Drive page: 68

- Shipbuilding: Inland Towing Thunderstruck page: 68

- No More ‘Tug Dilemma’ page: 70

- Reintjes: Changing Gears page: 74

- Meet SFFD’s New Fireboat Technology page: 126