English Channel

-

- The Hunt for the Notorious U-Boat UB-29 Marine Technology, Sep 2018 #10

A wreck-diving archaeologist and his quest to discover a missing submarine

You get an idea before you even walk in his door that Tomas Termote’s life is bound up with the sea, or at any rate what lies beneath it. Outside his house in Ostend, on the Belgian coast, stands the biggest anchor you’ve ever seen—over 16 feet high, weighing five tons. It was hand-forged for an old British man-of-war, and a trawler hauled it up from the seabed of the English Channel, a stone’s throw from here.

Out in the backyard, there’s a creepy-looking mine from the First World War, about a foot in diameter and prickly all over with detonators. It too came from nearby waters. The Germans occupied the entire Belgian coast during World War I. Their U-boats were based farther inland in Bruges, just outside the range of British naval guns, and passed through canals that fed into the channel at Ostend and the nearby town of Zeebrugge. The dunes outside Termote’s house are still lined with concrete bunkers built by the Germans to defend its U-boat bases from British attack. It was mines like the one in Termote’s backyard that sent more of Germany’s WWI U-boats to the bottom of the channel than anything else.

Termote started diving the icy English Channel at age 14 with his father, Dirk, a retired hotelier. Along the way, he picked up a degree in marine archaeology—a subject that barely existed when he started studying it—and has been studying wrecks around the world ever since. But the vast U-boat cemetery that starts just outside his front door is what he most loves to explore. To date, he has found the remains of 28 U-boats down there, 11 in Belgian waters. His book about U-boats, War Beneath the Waves, was published last year. One newspaper headline called him “the Flemish Indiana Jones.”

Termote is a compact, broad-chested man, soft-spoken and amiable. For most of the year, he makes his living diving commercially around the Belgian ports. Summer is for combing the local waters for wrecks, which are getting tougher to find all the time. The seafloor has been well mapped and picked over by now. Yet only last summer Termote stumbled across his most important discovery yet.

In the spring of 2017, Termote was checking Belgian hydrographic department documents online to see if any previously charted wrecks had shifted on the seabed. He took a passing look at one of these flagged wrecks lying some 80 feet deep about 12 miles straight off Ostend. “She’s been on the chart since 1947,” says Termote. “In the 1980s, she was identified as an upturned landing craft, like the ones in Saving Private Ryan. So it didn’t sound very interesting.” Modern multi-beam echo-sounders—the sonar devices now used for hydrographic surveys—are far more sensitive than earlier technologies. “Today you can almost see the links in an anchor chain. This was obviously not a landing craft. It wasn’t shaped like a biscuit tin, but like a cigar, with two pointy ends and a tower in the middle. The surveys also give you the length, and this was 26 or 27 meters. I was like, Bloody hell! This has to be a submarine!”

The original faulty identification had almost certainly thrown other wreck hunters off the scent. It helped, too, that the sub lay in the middle of a shipping lane, further discouraging the curious. “Every 15 or 20 minutes, you get 200-meter tankers passing over it—it would be like diving on a freeway.”

Since 2013, the governor of West Flanders, which includes Belgium’s short seacoast, has been Carl Decaluwé. In addition to his other duties, Decaluwé is Belgium’s Receiver of Wrecks, which means he has authority over anything found in Belgian territorial waters. He’s another of Termote’s old friends, not to mention a maritime history buff. So when Termote went down for the first time last June, maritime police were standing by and coastal radar had been alerted; a 1,000-foot exclusion zone kept commercial shipping from the dive site. “In the first half-minute, I knew it was a German UB II-class submarine,” remembers Termote. “After 30 U-boats, you just feel it. I can’t describe the elation I felt when I came up.”

Termote made six dives that summer. The submarine was indeed a UB Class II U-boat. Both periscopes had been bent forward. Swimming around the bow, Termote saw that the top starboard torpedo tube had been twisted and ripped in what must have been a massive explosion—UB II-class subs had two tubes on each side, one on top of the other.

Miraculously, given that it had been so violently sunk, the sub had escaped more extensive damage and was largely intact. “Finding a U-boat in such a condition is unique,” says Termote. “Most are heavily damaged—blown in two, or heavily salvaged. You won’t find another like this.” Still, the identification number painted on the conning tower was missing, corroded over time. At a press conference last September, when Belgian authorities announced the discovery, the sub’s identity remained a mystery.

In the absence of tower markings, the surest way to identify a U-boat is by its bronze propeller, often stamped by date and, if you’re lucky, serial number. Termote went down again and examined the U-boat’s stern. The port-side propeller had been sheared off. Termote suspects it was lost when Belgian authorities had “wire-dragged” the sea down to 25 meters to make sure nothing sticking up any higher could endanger local shipping. The starboard propeller was still there, but was made of iron and unmarked—the first time Termote had found a U-boat with an iron propeller. “By the end of 1916, U-boat crews knew they were on a suicide mission because the British had gotten so good at detecting and destroying U-boats,” says Termote. “Why bother putting a nice propeller on her?”

Termote made a final dive before winter last November. To put a name to his U-boat, he hoped to match a number on the periscope with records from the optics supplier, Berlin’s C.P. Goerz. He did find the number—417—but the Goerz archives, he learned, no longer exist. “On the dive, I started cleaning the torpedo tubes; you can find markings there,” says Termote. “Clean, clean, clean—and this ten-centimeter plaque comes free. It says, UB-29. I can’t describe that feeling.”

UB-29 was based in the medieval town of Bruges as part of the Flanders Flotilla, Germany’s English Channel fleet. The sub first took to sea in March 1916. At the helm was Herbert Pustkuchen, who was to become one of Germany’s most deadly U-boat aces. Pustkuchen ranks 31st among 37 commanders who each sank over 100,000 tons of Allied shipping during World War I. For this he won two Iron Crosses and the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern.

Pustkuchen is best known not for the ships he sank, but for one he didn’t. On March 24, 1916, Pustkuchen sighted a cross-channel ferry, the SS Sussex, en route from Folkestone in England to Dieppe in France with 325 passengers aboard. With no prior warning, UB-29 fired a torpedo from 1,400 yards, tearing off the ferry’s bow. Lifeboats were lowered, but several capsized. At least 50 passengers lost their lives. The Sussex managed to stay afloat and was towed, stern-first, to France. There were Americans on board the Sussex, and several were among the wounded. Pustkuchen had kicked a hornet’s nest.

Less than a year before, a German U-boat sank the liner Lusitania in the Irish Sea, and 128 Americans died. President Woodrow Wilson put Germany on notice that “unrestricted submarine warfare”—the shoot-first tactic that U-boat skippers took up after early losses—would bring the United States into the war. Now UB-29 had done it again, and Wilson threatened to break diplomatic relations. Cowed, Germany signed the “Sussex Pledge.” Henceforth, her U-boat captains would surface and search merchant ships for munitions. If armaments were found, the sub crew could sink the ship, after allowing its merchant crew to board lifeboats. Passenger shipping would be spared. These were known in maritime law as “cruiser rules,” reducing the effectiveness of U-boats, now denied their surprise torpedo attacks.

UB-29’s last patrol came less than a year after it entered service, under a new captain, Erich Platsch. (Herbert Pustkuchen went down with his crew in June 1917, when his UC-66 was bombed by a Curtis flying boat near England’s Scilly Isles; the wreck was found in 2009.) It was Platsch’s second time out. On December 13, 1916, UB-29 was spotted by the British destroyer HMS Landrail near the Strait of Dover. The Landrail managed to ram the sub before it could fully submerge. The destroyer dropped several depth charges over the side (the depth-charge launcher had yet to be invented). UB-29 was never seen again. Around midnight, Landrail’s searchlights picked out oil and debris on the surface of the water.

The weather was bad and the night was black. Landrail headed for home. In the absence of conclusive evidence, Landrail was never credited with an official kill, but the crew was awarded prize money anyway. English authorities marked the unseen grave of UB-29 southwest of the Goodwin Sands, six miles off the coastal town of Deal in Kent.

By early 1917, the German high command had concluded that it would be hard-pressed to win the war of attrition on the Western Front. The Allies could shovel men and arms into the mouth of war faster than Germany. Some two weeks after UB-29 went down, German Adm. Henning von Holtzendorff, in so many words, called for an end to the pledge it had provoked, and urged Germany to let U-boats fire at will. Holtzendorff predicted that Allied shipping losses would climb to 600,000 tons a month for the first four months, almost double their rate under cruiser rules. Losses would continue at 400,000 tons a month. England, crippled by falling food stocks, industrial strikes and economic chaos, would sue for peace in five months. At a conference in the German town of Pless on January 9, 1917, the German High Command decided that unrestricted submarine warfare would commence February 1.

Here’s what Termote thinks happened to UB-29. When the Landrail rammed the sub, the impact bent the two periscopes simultaneously, which is why he found them at the same angle. The depth charges wounded it and ruptured its oil tanks. But, he argues, UB-29 crawled away, slowly limping the 60 or so miles back home on compass. Platsch and his 21 crewmen must have felt a wild elation. “They were probably celebrating their escape—‘We’re going to be home in an hour! We made it! Let’s party, drink champagne!’ And then Boom!” Termote suggests that UB-29 hooked a mine with one of the twisted periscopes, dragging it down directly onto its hull.

UB-29’s last moments must have been slow and horrible. “You can see the damage is limited to the bow, so you could imagine that the people from the command center up to the engine room might still have been alive afterwards. It’s not like the U-boats you find blown in half where everybody dies immediately,” says Termote. As the water rose inside the hull, the crewmen may have cut short their inevitable agony by shooting themselves with their long-barreled service Lugers. Or they may have stuffed cotton in their mouths and noses and drowned themselves. Both were known to happen. “Terrible,” says Termote. However they met their end, they lie within UB-29’s steel walls, buried in the sand that has filtered through its cracks for a hundred years.

Copyright 2018 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

-

- EU to Develop Sulfur Strategy Maritime Reporter, May 2002 #43

is in the frame, says Adams. An EU study now underway will quantify ship emissions of S02, NOx, C 0 2 and hydrocarbons in the North Sea, Irish Sea, English Channel, Baltic Sea, Black Sea and Mediterranean, on the basis of year 2000 ship movements. The commission is also taking advice on the costs to the

-

- Superseacat Service To Be Launched Maritime Reporter, Feb 2000 #35

operate between Tallinn and Helsinki in 90 minutes at an average speed of 37.8 knots, about 42-rpm. Already operating on the Irish Sea and English Channel are Superseacat's trio of sisterships, offering a smooth ride resulting from an underwater wing called a T-foil, which acts as a stabilizer

-

- Intermarine UK Investment Boosts Portland Port Activities Maritime Logistics Professional, Jul/Aug 2018 #34

best-located ports in Britain,” he said. “It sits on pole position for naval and commercial shipping operating on the south coast of England and the English Channel. Our aim is to complement the range of maritime services already available at the port by offering more extensive ship repair facilities, encouraging

-

- Spanish Ferry Company Adds Second Jetfoil In Canary Islands Service Maritime Reporter, Mar 15, 1981 #38

million passenger miles in worldwide operations since beginning service in April 1975. The Belgian state ferry company RMT (Sealink) will begin English Channel Jetfoil service on May 31 this year between Ostend, Belgium, and Dover, England

-

- Boeing Jetfoil Sold To Argentine Owner—Christened Montevideo Jet Maritime Reporter, Sep 15, 1980 #24

. The Alimar operation will be the fifth Boeing Jetfoil service to begin this year. Other passenger services were inaugurated in 1980 on the English Channel, the Irish Sea, in the Canary Islands, and in Puget Sound between Seattle and Victoria, British Columbia. Fifteen Boeing Jetfoils are now in

-

- Navy To Procure Five Boeing PHM Hydrofoils Costing $282.1 Million Maritime Reporter, Feb 15, 1977 #20

, during its two-month demonstration trip. Following the demonstration tour, it is expected to be placed in commercial ferry service on the English Channel. As configured, the full capacity of the Flying Princess is 234 passengers

-

- U.S. Firms Share In New U.K. Licenses For Offshore Oil Maritime Reporter, Mar 1977 #36

Britain. They involve approximately 18,000 square miles in the North Sea, Irish Sea, Cardigan Bay (West Wales), and the yet unexplored areas of the English Channel and the west of Scotland. The oil companies involved include most of the major U.S. firms already active in North Sea operations. All applicants

-

- Avco Lycoming Powers Hovercraft Carrying 400 People & 45 Cars Maritime Reporter, Jul 1978 #15

On June 4, a unique French hovercraft made its inaugural "flight" across the English Channel between Dover, England, and Calais, France. The vessel is powered by five marine gas turbines manufactured by the Avco Lycoming (Stratford, Conn.) Division. The craft, designated N500-2, was built by the

-

- N e w Gladding-Hearn-Built High-Speed Catamaran To Begin Boston/Martha's Vineyard Run Maritime Reporter, May 1988 #48

Islands on the West Coast at about 28 knots. Other INCATs are in use in Marin County, Vallejo and San Francisco, Calif., Alaska, Hong Kong and the English Channel. For more information and free literature on the capabilities and facilities of Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding, Circle 50 on Reader Service Car

-

- W e s t a m a r i n Delivers M T U - P o w e r ed A l l - A l u m i n um Reefer C a t a m a r an Maritime Reporter, Dec 1987 #62

, Honefoss. The 164-foot-long by 46-footwide "Thermoliner" will mainly be used for transportation of fresh fish from Scandinavia to ports in the English Channel, with return freight of frozen food, flowers, fresh vegetables, etc. The main deck of the catamaran is insulated and divided into one refrigerated

-

- Boeing Sells Jetfoil To Canadian Company For Marine Research Maritime Reporter, Feb 15, 1985 #22

Jetfoils are operating in commercial passenger service between Hong Kong and Macao, in the Sea of Japan, in the Canary Islands, and across the English Channel. Boeing has also sold Jetfoils to the Republic of Indonesia for coastal patrol service

-

)

September 2023 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 44

)

September 2023 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 44just 10kg and measuring under one meter ies, a type of lithium primary battery that use a lithium metal in length, when it successfully crossed the English Channel in anode and a liquid cathode that doubles as the electrolyte. The less than eight hours. RS Aqua’s Ocean Scientist, Nathan Hunt, cells have

-

)

August 2020 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 14

)

August 2020 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 14. Some years ago a during the period 2008-2019. ship suffered a casualty transiting the Until recently, governments only got involved in contain- English Channel in a storm. Much of its er losses if they created a hazard to navigation (such as by C cargo of lumber and other ? oating items ? oating)

-

)

Jul/Aug 2018 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 35

)

Jul/Aug 2018 - Maritime Logistics Professional page: 35ports in Britain,” he said. “It sits on pole position for naval and commercial shipping operating on the south coast of England and the English Channel. Our aim is to complement the range of mari- time services already available at the port by offering more exten- sive ship repair facilities

-

)

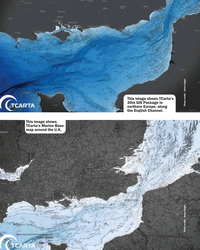

April 2018 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23

)

April 2018 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23This image shows TCarta’s 30m GIS Package in northern Europe, along the English Channel. This image shows TCarta’s Marine Base- map around the U.K. Photo credit - Aaron Sager Photo credit - Aaron Sager www.marinetechnologynews.com Marine Technology Reporter 23 MTR #3 (18-33).indd 23 MTR #3 (18-33).

-

)

November 2016 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 26

)

November 2016 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 26, the components of the harbors were survey under sail at one point. In the ? rst phase of the work, manufactured in the U.K., towed across the English Channel 350 separate wrecks and debris were marked, and in the sec- and assembled off the coast of Normandy. Mulberry A, was ond phase 50 speci? c targets

-

)

November 2016 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23

)

November 2016 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23very high velop equipment and methods capable of transferring an army resolution color three-dimensional images of the seabed, in- across the English Channel. Many of the innovations that cluding many remaining artifacts from the D-Day landings. were employed were previously untested in warfare, and

-

)

April 2016 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 12

)

April 2016 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 122007, during heavy packed containers. After deliberation, SOLAS committee (sic) did not ref- ous incidents where the actual mass of weather in the English Channel, the con- DSC approved the recommendation erence any instance where a ship had a container has far exceeded the mass tainer ship MSC NAPOLI

-

)

February 2015 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 49

)

February 2015 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 49. opment in the Danish sector. ships on the North Sea, Baltic Sea and which aims to develop or enhance tech- Denmark houses a range of shipping the English Channel. nologies which reduce emissions and Offshore supply companies which specialize in Founded in 1871, D/S Norden (Damp- particles from sulphur

-

)

September 15, 1980 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 22

)

September 15, 1980 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 22. The Alimar operation will be the fifth Boeing Jetfoil service to begin this year. Other passenger services were inaugurated in 1980 on the English Channel, the Irish Sea, in the Canary Islands, and in Puget Sound between Seattle and Victoria, British Columbia. Fifteen Boeing Jetfoils are now

-

)

March 15, 1981 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 36

)

March 15, 1981 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 36passenger miles in worldwide operations since beginning serv- ice in April 1975. The Belgian state ferry company RMT (Sea- link) will begin English Channel Jetfoil service on May 31 this year between Ostend, Belgium, and Dover, England. Walter Gregorek Joins New York Sales Staff Of Midland

-

)

December 1987 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 50

)

December 1987 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 50. The 164-foot-long by 46-foot- wide "Thermoliner" will mainly be used for transportation of fresh fish from Scandinavia to ports in the English Channel, with return freight of frozen food, flowers, fresh vegetables, etc. The main deck of the catamaran is insulated and divided into one

-

)

November 2001 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 15

)

November 2001 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 15. Once again, the requirement for both bow and stern door access in the previous series was determined by the nature of the Irish Sea and English Channel trades, where rapid turnarounds in port and high ship productivity are operational and commercial necessities. The Spanish vessel's hydraulical

-

)

October 2003 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 8

)

October 2003 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 8maritime his- tory. The first British battleship to be torpe- doed by a German submarine was HMS Formidable, sunk just off Portland Bill in the English Channel in 1915. A few hours after ther sinking, some fishermen found the body of a seaman that had been washed ashore in Lyme Bay; they carried

-

)

July 2004 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 30

)

July 2004 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 30to restrict SOx emissions. The first SECA will be the Baltic Sea, with effect from 2006. It is anticipated that the North Sea and parts of the English Channel will be designat- ed as SECAs in 2007. Renewing the R&D Base One hundred years on from the opening of the Felling site on Tyneside for

-

)

August 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 38

)

August 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 38other engi- neering tasks. British Hovercraft developed the 190-ton SR.N4 Hovercraft, five of which have been in daily passenger service on the English Channel for the last 4y2 years. The SR.N4 seals are similar in geometry and approximately one- half scale of those which will contain the air cushion

-

)

July 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 5

)

July 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 5has been applied to a unit of this weight. Previously, the heaviest air cushion vehicles were 180-ton ferries, which currently ply the English Channel. "This type of transporter is unique, however, because it is not self-propelled, thereby eliminating the most expensive and sophisti- cated

-

)

June 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 6

)

June 15, 1973 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 6the equivalent background of 17 ship years of day- by-day operation. This experience in the un- predictable weather conditions of the North Sea, English Channel, Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean, he said, is unequaled by any other LNG ship design, and gives the ship- owner confidence that he will

-

)

September 2013 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 29

)

September 2013 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 29Loran (eLoran) system. The United Kingdom has deployed a small eLoran network, but it is primarily effective only in the vicinity of the English Channel. Un-til and unless a wide-scale earth-based system such as eLoran is available, ships and aircraft will be vulnerable to spooÞ ng attacks

-

)

February 2013 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 15

)

February 2013 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 15(MCA) directs vessels to places of refuge when he judges it appropriate. On 18 January 2007, the container ship MSC NAPO-LI was transiting the English Channel in heavy weather en route South Af- rica. It suffered a catastrophic struc- tural failure, causing rapid flooding. A distress message was

-

)

December 2012 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 22

)

December 2012 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 22President and CEO of Virtual Marine Technology (VMT) of St. John?s, Newfoundland, cites the MSC Napoli?a container ship that had to beevacuated in the English Channel in 2007 due to hull damage. ?The convention is clear,? he says. ?You have to demonstrate your competence to do this job using realequipment. This

-

)

June 2012 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 24

)

June 2012 - Maritime Reporter and Engineering News page: 24(ECAs). At present, sul- phur emissions control areas (SECAs)are in effect in the Nordic region and the Baltic Sea and ECAs will be establishedin the English Channel, North America and some islands in the Caribbean. Earlier this year, the EU published a consultation document which considereda number of options

-

)

June 2012 - Marine News page: 58

)

June 2012 - Marine News page: 58has introduced tidal opti- mization as a tool for improving effi- ciency on coastal shipping routes. In simulations developed for transits through the English Channel, a time difference of 12.8 per cent was shown between best case and worst case passage times when using optimal tide and current (based on

-

)

November 2011 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 30

)

November 2011 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 30, but also a lot of fun. So I went off on expeditions, some were with Doc Edgerton who was great to travel with. For example we went and sur- veyed the English Channel. This was in the early 60?s. There had been a plan for a hundred years to put a tunnel between England and France. We had a project to study the

-

)

May 2010 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23

)

May 2010 - Marine Technology Reporter page: 23. 22 MTR A pilot project completed in 2008 by Bournemouth University demonstrated the potential for correlations to exist within the Eastern English Channel, leading to the commissioning of AMAP2 to further investigate and quantify these relationships across a much larger area encompassing all of England's