By Guy T. Noll

“When you've been to one port, you've been to one port.” So goes a saying exemplifying the understanding among the maritime community that every port is inherently unique. Each port has an exceptional identity and, likewise, an exceptional way in which its problems must be presented, addressed and solved. Each port's challenges are location-specific, from the range of tide levels and other environmental conditions to governance by political jurisdictions. There are also economic drivers determined by location.

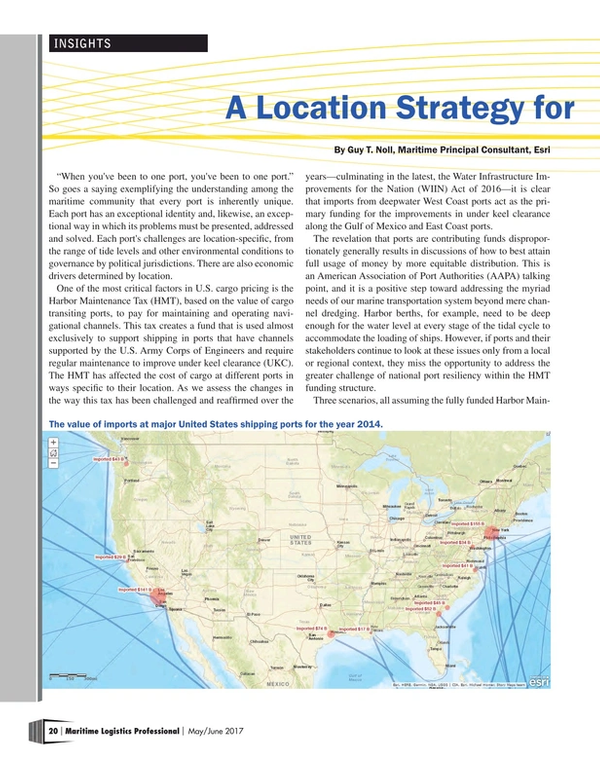

One of the most critical factors in U.S. cargo pricing is the Harbor Maintenance Tax (HMT), based on the value of cargo transiting ports, to pay for maintaining and operating navigational channels. This tax creates a fund that is used almost exclusively to support shipping in ports that have channels supported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and require regular maintenance to improve under keel clearance (UKC). The HMT has affected the cost of cargo at different ports in ways specific to their location. As we assess the changes in the way this tax has been challenged and reaffirmed over the years—culminating in the latest, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act of 2016—it is clear that imports from deepwater West Coast ports act as the primary funding for the improvements in under keel clearance along the Gulf of Mexico and East Coast ports.

The revelation that ports are contributing funds disproportionately generally results in discussions of how to best attain full usage of money by more equitable distribution. This is an American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA) talking point, and it is a positive step toward addressing the myriad needs of our marine transportation system beyond mere channel dredging. Harbor berths, for example, need to be deep enough for the water level at every stage of the tidal cycle to accommodate the loading of ships. However, if ports and their stakeholders continue to look at these issues only from a local or regional context, they miss the opportunity to address the greater challenge of national port resiliency within the HMT funding structure.

Three scenarios, all assuming the fully funded Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) is still in use by 2020, highlight the need to look at ports as a unified structure for national economic security:

Scenario 1—Winners Keep Winning

The HMTF is primarily used as an appropriations offset for UKC management to continue funding U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredging operations. These funds will enable the continuation of building capacity for Neopanamax freight traffic as well as deepening berths alongside in the major ports. Continued HMT and cost-share revenue will provide sufficient funding under WIIN to complete the projects.

For the ports that cannot create the perceived need for these investments, no substantive change will occur, and larger traffic is going to pass them by. Not only that, but the ability to create short sea shipping routes from the "winner ports" to the lesser ports will be impacted by both the cost of protectionism of re-importing containers or semi-processed bulk goods, and the complex and opaque rules governing HMT rebates.

Scenario 2—Lake Wobegon

Much like Garrison Keillor's fictional town Lake Wobegon, “where all the children are above average,” HMT revenue continues to grow while the sharing behavior to ensure equity is somehow achieved. This would occur only as major and favored port UKC projects are replaced by other port requirements, continuing to the midtier ports and maybe even some of the harbors of refuge and subsistence ports under some scoring criteria that would manage to prioritize regionalism. Such criteria would need to be transparent to achieve this outcome.

Scenario 3—A Broken System

Suppose a long-term, national challenge to the ports system occurs. The frame of reference for such an impact would be something even greater than the 2012 port clerks strike in Los Angeles/Long Beach, which cost the region $8 billion, and more substantive than the trucker strike of 2015. While these shutdowns can be mitigated through port-to-port agreements, an environmental crisis would be beyond that level of control. What if, for example, global water levels increase due to melting of Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets? In some models, such increases could occur rapidly, like the observed changes in glacier thinning in Alaska, Nepal, and Patagonia. Such a discontinuity in the historic record of sea level would create wide-ranging impacts for the nation, including waterfront parcel loss, reinsurance losses, and coastal pollution. It would also imperil the infrastructure at many ports, from laydown areas to wastewater facilities.

Charting the Route through Future Challenges

Port infrastructure investments will be put at greater risk with sea level rise, and mitigation of these risks will require rebalancing HMTF usage from deepening channels to shoreside facilities management. This will have higher differential impacts at the smaller ports with less robust connections to shore transportation hubs, but it may also show some local resiliency as changes are made over a decade or so.

What can be done? Ports need to become active in managing these infrastructure risks. Per WIIN, key steps must be identified: assess current infrastructure with a focus on risks due to flooding at key shipment transfer points; monitor local changes through actively measuring the trends at the port; create regional failover points for transshipment activity, similar to the ways that strikes have been mitigated in the past; develop an environmental consequence plan for ports that mitigate the impacts from non-point-source pollution, flooded laydown areas, storage tanks, and pipeline corridor damage; and develop plans for ballast water management.

Now is the time to create dialog with U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other agencies and stakeholders to develop scenarios for the high-risk/lower-probability environmental or other sea level changes that could have national impacts on the HMTF funding stream, and determine how to maintain the revenue for improving infrastructure.

Shipping involves more than simply carrying goods from point A to point B. A successful port strategy is about safely and sustainably carrying the right goods to the right place by the right time and for the right price. The information to mitigate shipping risk must be sensitized to where the shipment is headed, or the national shipping framework may fail when challenged by the large environmental changes that affect the shore. A resilient shipping system means making location and time the centerpiece of port infrastructure planning.