US SHIPBUILDING OUTLOOK Markets & Cost Saving

Editor's note: The following report is reprinted from the 1984 Annual Report of the Shipbuilders Council of America that was released in April, 1985.

For the shipbuilding and shiprepair industries, 1984 was a year in which "holding ground" was a primary operative phrase. The present policy of the Administration is that our industry must fend for itself as best it can, and survive as best it can despite the projected deficiencies in our ability to meet military requirements.

Indeed, even steps that could have been taken without direct cost to the government and which would have been supportive of the shipbuilding industry were not implemented.

Among these are withdrawal of the proposed rule that would allow the repayment of construction differential subsidy (CDS) by operators to qualify affected vessels for Jones Act trading privileges. The threat of rule promulgation continues to disrupt the Jones Act market for operators and thwarts shipbuilding potential.

A tolling of the litany of failures in policy planning and the execution of maritime policy does not need to be repeated. My message in the 1983 Shipbuilders Council Annual Report can be redated, as current, without fear that important gains have been neglected.

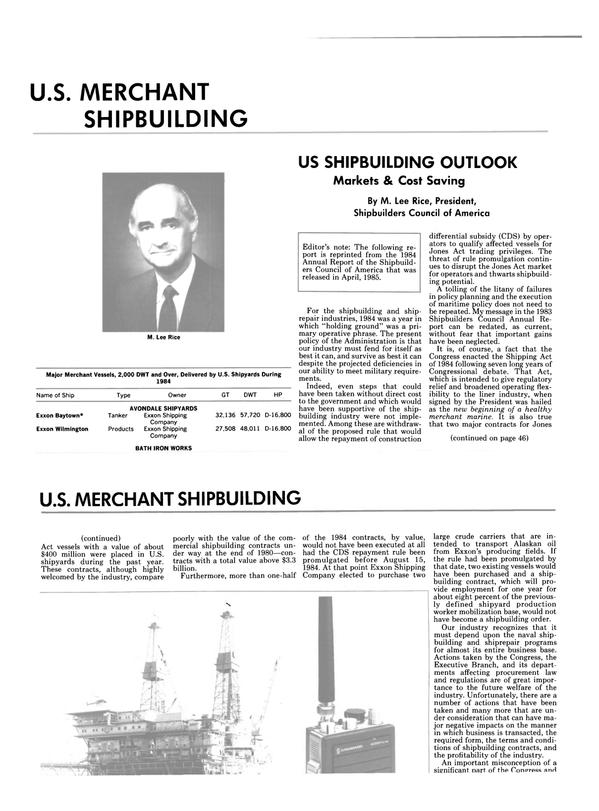

It is, of course, a fact that the Congress enacted the Shipping Act of 1984 following seven long years of Congressional debate. That Act, which is intended to give regulatory relief and broadened operating flexibility to the liner industry, when signed by the President was hailed as the new beginning of a healthy merchant marine. It is also true that two major contracts for Jones Act vessels with a value of about $400 million were placed in U.S.

shipyards during the past year.

These contracts, although highly welcomed by the industry, compare poorly with the value of the commercial shipbuilding contracts under way at the end of 1980—contracts with a total value above $3.3 billion.

Furthermore, more than one-half of the 1984 contracts, by value, would not have been executed at all had the CDS repayment rule been promulgated before August 15, 1984. At that point Exxon Shipping Company elected to purchase two large crude carriers that are intended to transport Alaskan oil from Exxon's producing fields. If the rule had been promulgated by that date, two existing vessels would have been purchased and a shipbuilding contract, which will provide employment for one year for about eight percent of the previously defined shipyard production worker mobilization base, would not have become a shipbuilding order.

Our industry recognizes that it must depend upon the naval shipbuilding and shiprepair programs for almost its entire business base.

Actions taken by the Congress, the Executive Branch, and its departments affecting procurement law and regulations are of great importance to the future welfare of the industry. Unfortunately, there are a number of actions that have been taken and many more that are under consideration that can have major negative impacts on the manner in which business is transacted, the required form, the terms and conditions of shipbuilding contracts, and the profitability of the industry.

An important misconception of a significant part of the Congress and congressional staff members, as well as executives who administer defense procurement, is that government contracting should be done under ever more restrictive rules, contract terms, and procurement procedures. We can understand the desire of the Congress and administrators to achieve reduction in the costs of defense procurement and to increase the efficiency of the process.

A point exists, however, when efforts to control contractors' costs by additional audit and reporting requirements, changes in the definition of allowable costs, and required contract terms and conditions becomes counterproductive.

There have been significant changes to federal procurement law in the past two years. At this time, it is impossible to determine their ultimate impact on overall costs.

However, without waiting to measure the effect of recent "reforms," additional changes are being suggested in the form of legislation or are being implemented through administrative edict.

The government contracting process is a complex system. We fear that we have entered an operating environment when two dollars will be spent in administrative costs or final contract costs in the hope that one will be saved. This, at best, is false economy. The government gains tremendously when contractors can earn competitive profits from government work and are stimulated to invest earnings to acquire improved plant and productivity gains. Profits and cash flow resulting from government contracts are an essential requirement if the entire government contracting process is to function efficiently and private investment in new and renewed capability is to occur.

Profits earned should be regarded by the government as an important tool through which efficiencies and lower future costs can be achieved.

Profits must not become a "dirty word." The government should recognize, and act, in accord with its dual role of operating partner who gains in its tax collector role from profits earned and in its customer role from efficiency and cost gains that result from private investment.

Within the naval shipbuilding budget (SCN) there are three primary elements of cost. These are: (1) costs incurred by the Navy in management of the procurement system; (2) costs incurred by the Navy in the procurement of government- furnished equipments and materials that, in turn, are delivered to the shipyards; and (3) contracts with the shipyards for the construction of vessels. Of the total SCN expenditure, only about 40 percent is the value of shipyard contracts.

Of this amount, roughly one-half purchases the services and skills of the shipbuilder. The other half of the contract cost is expended by the shipbuilder to purchase materials, equipments, and services supplied by others and required to build the ship.

Productivity and efficiency gains achieved by shipyards reduce costs controlled directly by the yards.

These are the cost of shipyard labor and overhead. To a much lesser degree shipyards, through good procurement practices, can cause reductions in the cost of purchased materials, equipments, and services.

To repeat: shipyards directly control, on the average, about one-half of the contract cost but only about 20 percent of the total SCN expenditure.

Thus, major gains in shipyard productivity translate into relatively small reductions in the total shipbuilding account. The Navy, on the other hand, can through its direct actions influence and affect the cost of the non-shipyard-controlled components of the budget, roughly 80 percent of the total expenditure, an amount that includes shipyard-purchased materials that are purchased to meet military specifications.

We have recommended, for a number of years, that the Navy aggressively pursue reductions in the cost of that part of the SCN budget that is under its control and beyond the control of the shipyards.

To "get at" these potential cost reductions, we recommend that the Navy undertake a meaningful selfappraisal of its procurement practices and the cost of administration of shipbuilding programs.

We have often asserted that there are major cost savings to be gained from survey, review, and revision of (1) the General Specifications that define ship design criteria and characteristics, and (2) the Military Specifications that fix definitional standards for all purchased equipments and materials. Achievement of adequate system performance at lowest cost has never been a primary objective in development of this fundamental documentation. We believe that cost must be considered as a primary objective in the development and/or modification of these controlling specifications.

Materials and equipments procured each year under the Military Specifications alone cost the Navy, its weapons systems suppliers, and the shipbuilders billions of dollars.

It is recognized that a balance between performance requirements and cost reductions must be realized.

To not pursue cost gains through specification change is an abrogation of responsibility.

The potential for cost saving is large. What is required is that the Navy fund and carry out study and revision of these specifications, with engineering, test, and evaluation as necessary. This approach has been proposed on an almost annual basis for a number of years. Unfortunately, because the payoff is in the out years, the program is annually among the first to be "axed" to gain shorter-term objectives in the funding of ship construction projects.

We continually are asked to reduce shipbuilding and shiprepair costs. The record shows that the shipbuilding industry has made major cost reduction advances. We now believe that we are justified in asking that the Navy make similar reductions in their controlled costs, and that the Congress gain full understanding of who and what actually controls each of the primary elements of shipbuilding costs.

The potential for achieving ever lower shipbuilding costs is approaching a limit. Shipbuilding productivity and engineering advances, coupled with the intense competition that characterizes our industry, has resulted in lower selling prices.

The fact that shipbuilding and shiprepair has become an oligopsony, affects selling price and will cause major change in the industry.

In our view, it is time to turn attention to other cost drivers in the procurement process, and to begin consideration of diverse national security requirements in the development of a shipbuilding policy.

Read US SHIPBUILDING OUTLOOK Markets & Cost Saving in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of June 1985 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from June 1985 issue

Content

- McDermott Gets Contract From SOHIO To Build Offshore Drilling Platform page: 6

- Shipboard Safety Criteria Monitored By Siemens Computer page: 6

- Puroflow Gets Canadian Order For Ultraviolet Water Purification Systems page: 6

- Moss Point Marine To Build Victorian-Style Sternwheel Riverboat page: 7

- Fiberglass Passenger Vessel Built By Westport For Catalina Channel page: 8

- New Facility Opened By Lips Propellers At Todd-Seattle Shipyard page: 9

- Samson Offers Brochure On Passive Mooring Systems For Supply Vessels page: 9

- Marathon LeTourneau To Construct World's Largest Bottom Supported Mobile Offshore Drilling Unit page: 12

- GEC Rolls-Royce Gensets Selected For Shell/Esso Tern Offshore Platform page: 14

- A S S C O Elects B a u m l e r V P - M a r k e t i ng page: 15

- N e w B r o c h u r e F r om W e s t i n g h o u s e Discusses C o m b u s t i o n T r i m C o n t r ol page: 15

- Raytheon Introduces JRC Color And Digital Rasterscan Radar Unit page: 16

- Simpson Timber Restructuring Its Panel Products Division page: 16

- Ingersoll-Rand Signs Sales Agreement With Kawasaki page: 17

- Murray Grainger Resumes Business Activities As Used Equipment Dealer page: 20

- New Remote Control VHF Marine Radio Introduced By Uniden page: 20

- Mitsubishi Introduces Latest Diesel Engine At New York Seminar page: 21

- Contract For Wharf At Cow Head Oil Rig Servicing Facility Awarded page: 22

- Marathon LeTourneau Exhibits Slo-Rol® Motion Suppression Technology During 1985 OTC page: 23

- Aluminum Boats Delivers Whale Watch Excursion Boat page: 23

- I.T.C. Holland Engineers Its Third Double Rig Dry Transport On The Sibig Venture page: 25

- Hitachi Zosen Completes Two Power Generating Barges For Philippines page: 25

- FUTURE U.S. NAVY BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES —A $230 billion # 5 Year Market— page: 26

- US SHIPBUILDING OUTLOOK Markets & Cost Saving page: 44

- Secretary Dole Promulgates CDS Repayment Rule page: 44

- U.S. MARITIME ASSETS AND NATIONAL SECURITY page: 48

- THE CIRCLE OF RELIANCE " I n Time of War, Land, Sea, and Air Forces and All Logistic Support Functions Must Work as a Team" page: 50

- THE GOVERNMENT AS PARENT TO INDUSTRY: PARTICIPATION OR BENIGN NEGLECT? page: 52

- A SUCCESSFUL MARITIME POLICY UNDER ATTACK page: 58

- Offshore Service Vessels, Tugboat And Inland Towboat Fleets page: 60

- U.S. COULD LEARN A LESSON FROM GREAT BRITAIN'S OFFSHORE OIL LEASING page: 65

- CANADIAN SHIPBUILDING — 1985 — page: 76

- Liu Elected Vice President Of American Bureau To Head R&D Division page: 79

- VTHE NEW DDG-51 CLASS GUIDED MISSILE DESTROYERS —A Report— page: 80

- Harris Gets Subcontract To Supply HF Equipment For Canadian Frigate Program page: 89

- Brochure On "Sea Float" Marine Buoys And Floats Offered By Seaward page: 89

- Multi-Purpose Freighters To Be Built By Seebeck page: 89

- Omnipure Awarded $1.3-Million Contract From Canadian Navy page: 90

- New IMA Report On Future U.S. Navy Procurement Now Available page: 90

- Dubai Drydocks Reports Profit For Second Year page: 91

- Farboil Offers Free Four-Color Folder On Wetsall® Coatings page: 91

- Devoe Offers Brochure On Marine And Corrosion Control Paints & Coatings page: 92

- New Portable Hoists Line With Failsafe Brakes Now Available From PHD page: 92

- World Transport Coordinates Wet Tow Of Western Oceanic Rig page: 93

- Marinette Marine Installs First DWB Ship Transfer System In North America page: 93

- Norcontrol Offers Brochures On Navigation/Instrumentation Line Marketed In U.S. By Nav-Control page: 94

- Nichols Brothers Builds New McNeil Island Ferry page: 97

- Rowan Offers Free Literature On Drill Rig 'Rowan Gorilla IV' page: 97

- Raytheon Introduces Newest SatCom For Fishing And Pleasure Craft page: 98

- Crawford Fitting Introduces Gap Inspection Gages For SWAGELOK Tube Fittings page: 98

- Jeffboat Delivers Deck Barge For Nugent Sand Company page: 99

- Unique Actuator Selection Slide Chart Available From Jamesbury Corp. page: 99

- CRUISE '85 SHIPS • OPERATIONS • SERVICES page: 100

- Aeroquip T-J Division Offers New Series TP Proximity Switches page: 101

- Valcor Catalog Includes Products For Marine And Naval Applications page: 102

- Apelco Introduces Loudhailer With Two-Way Intercom And Alarm Features page: 102

- Marine Management Develops Demo Programs page: 103

- Marco-Seattle Converts Two Combination Crabbers For New Fishery Roles page: 103

- Markey Supplies Tug With Two Capstans page: 104

- Southwest Marine Yard Repowering San Francisco Commuter Ferries With Detroit Diesel Allison Engines page: 104

- AMETEK Announces Computerized Inspection Management System page: 105

- "Marine Library" Literature Available From DDA page: 105

- Furuno Introduces FR-803D Digital Radar page: 105

- MariChem 85 page: 106

- LIQUID CARGO HANDLING EQUIPMENT —A Review— page: 108

- Marathon LeTourneau GranGulf™ Semi Design Offers Economic Construction & Optimum Deck Load page: 113

- First Interactive Shiphandling Simulators From Ship Analytics Being Commissioned page: 116

- Stewart & Stevenson 'Mean 16' Provides Patrol Boats With New Power And Cruising Range page: 119

- Literature Available On Navlink From Datamarine page: 119

- Elliott White Gill Names New Sales Agent For Taiwan page: 120

- Blackinton Named General Manager Of Bethlehem-Beaumont Yard page: 120

- DAMPA Continuous Ceiling Approved By U.S. Navy— page: 121

- Ingersoll-Rand Forms New Compressors Division page: 122

- Menge Named Agent For Seaward Fenders page: 122

- Lanzendorfer Will Manage Fairbanks Morse Service Facility in San Diego page: 124

- $5.3-Million Navy Program Received By Tracor page: 124

- Gensler Named Director Of Marketing And Sales For InterTrade Industries page: 124

- WABCO Offers 8-page Brochure On Logicmaster™ Marine Propulsion Control Systems page: 133

- Free 12-Page Color Brochure Availale From Falk On New Shaft Speed Reducer Line page: 133