Work‘bots’: Autonomous Vessels Arrive

The near-shore and inland workboat fleet is at the leading edge for autonomous vessel development

While the advent of autonomous workboats are not exactly mainstream, you better believe that in the not-too-distant future they will be a reality on waterways in and around the U.S. Today there remain more questions than answers, particularly on the legal, logistics and insurance side of the coin. But the technology is evolving at record pace, providing many in the industry with mixed emotions. Excitement. Controversy. Curiosity. Skepticism. These are just a few of thoughts, and emotions that arise to any mention of the topic of autonomous vessels.

It’s happening now. Out ahead of the rulemaking process, autonomous technology providers already churn out not just prototypes and designs, but also countless workboats, many already in service. In the last 12 months, these firms have been collectively busy.

Vancouver-based naval architects Robert Allan Ltd., and Kongsberg Maritime are collaborating on the development of a remotely-operated fireboat that will allow first responders to attack fires more aggressively and safer than ever before. Separately, in Korsør, Denmark, Boston-based Sea Machines demonstrated the capabilities of its SM300 product aboard an autonomous-command, remote-controlled, TUCO Marine built fireboat. Marine firefighting is an autonomous application that appears to have legs.

Sea-Machines also partnered with Marine Spill Response Corporation (MSRC) to autonomously control a Munson boat to deploy and tow a spill collection boom working in tandem with a 210-foot MSRC spill response vessel. In direct competition with Sea-Machines, ASV Global is working on autonomous projects with a similar focus. ASV recently partnered with UK’s Peel Ports Group to develop autonomous vessel technology for shallow survey operations. Spill response is also a big part of ASV’s product development efforts.

Another stakeholder, Florida-based SeaRobotics Corporation recently delivered two 2.5 meter autonomous unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) to the Canadian Hydrographic Service, a part of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, bringing the fleet to four systems.

More recently, towboat operator KOTUG demonstrated a remote-controlled tugboat over a long distance, from Marseille, France to Rotterdam. A KOTUG captain took control of the tug via remote secured internet line and camera images, all based in Marseille.

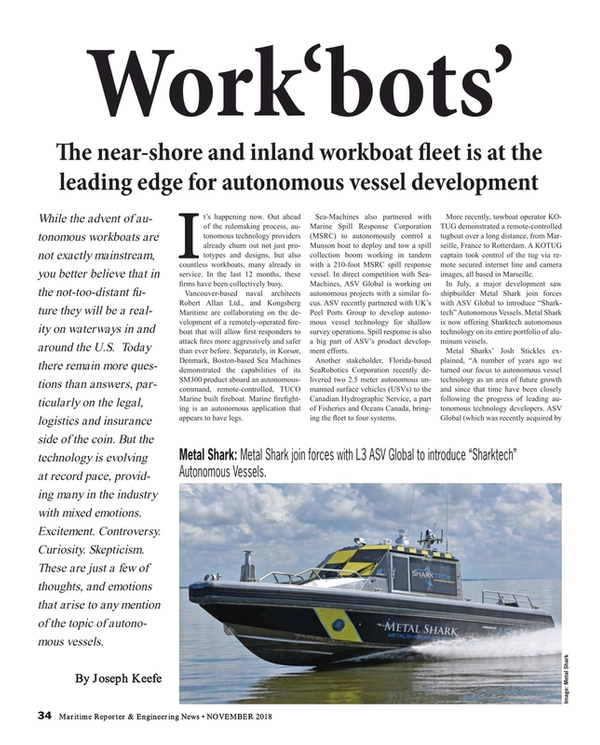

In July, a major development saw shipbuilder Metal Shark join forces with ASV Global to introduce “Sharktech” Autonomous Vessels. Metal Shark is now offering Sharktech autonomous technology on its entire portfolio of aluminum vessels.

Metal Sharks’ Josh Stickles explained, “A number of years ago we turned our focus to autonomous vessel technology as an area of future growth and since that time have been closely following the progress of leading autonomous technology developers. ASV Global (which was recently acquired by L3), who we felt was fairly well ahead of others in terms of the maturity and overall market-readiness of their technology, happens to be located right in our backyard (Broussard, LA). Their engineers and our engineers were a natural fit for each other, and our proximity has allowed for a very collaborative approach.”

Design & Regulate

Not so fast. The devil is always in the details. For example, classification society ClassNK recently released its Guidelines for Concept Design of Automated Operation/Autonomous Operation of ships. ClassNK isn’t the only IACS member to address the advent of autonomous vessels. Outgoing IACS Chairman & DNV GL Maritime CEO Knut Ørbeck-Nilssen believes that IACS rules must “… allow for such new technologies to be used, in the interest of safety and in the interest of the working environment for those people.”

As these rules evolve, flag states and registries will also have input. Tellingly, the U.S. Coast Guard led a delegation to the 99th session of the International Maritime Organization’s Maritime Safety Committee. This meeting advanced discussions on vessel autonomy. Last year, the IMO agreed to assess how existing international conventions would address advances in autonomy.

ASV Global CEO Thomas Chance shrugs off potential regulatory pitfalls, saying, “The regulators are being careful to provide a balance of guidance without killing the industry. ASV Global operates in a very transparent manner which likely helps our situation. Finally, all of our clients have been very rational about where and when they operate.”

But, naval architects and designers have many things to consider. If ‘Dull, Dirty and Dangerous’ is the catch-phrase that describes the best reasons to employ autonomous technology, there are also other reasons to explore this emerging, disruptive product. One main driver is lower capital and OpEx. An unmanned vessel does not need staterooms, heads, galleys, a wheelhouse, and other spaces found on conventional vessels. That vessel is much simpler, less expensive to build and maintain. With fewer (or no) crew, daily costs also shrink.

Vince den Hertog, RAL VP, Engineering, said, “There are capital cost savings from dispensing with the deckhouse, wheelhouse, domestic systems or lifesaving equipment, but these are offset by a premium for electronics, communications, sensing and operator console equipment to operate remotely.”

Vince den Hertog, RAL VP, Engineering, said, “There are capital cost savings from dispensing with the deckhouse, wheelhouse, domestic systems or lifesaving equipment, but these are offset by a premium for electronics, communications, sensing and operator console equipment to operate remotely.”

There are trade-offs. The end-user might pay a premium for the control system, but also achieve savings in other areas. Vince den Hertog, RAL Vice President, Engineering, agrees. “There are capital cost savings from dispensing with the deckhouse, wheelhouse, domestic systems or lifesaving equipment, but these are offset by a premium for electronics, communications, sensing and operator console equipment to operate remotely. In the end, the cost difference will not be prohibitive since the capital cost of the vessel remains driven mainly by hull structure and major equipment/machinery.”

Metal Shark’s Stickles takes a similar tack. “Take a look at the 38-ft. Defiant Sharktech autonomous vessel, for example. As configured, it’s got expensive Pillarless Glass, expensive shock-mitigating seats, special flooring for sound deadening and vibration mitigation, climate control, an enclosed head, full galley, and the list goes on. We could offset a significant portion of the cost of technology today by eliminating crew amenities. A true unmanned vessel can be ‘leaner and meaner.’ So, efficiency is a key consideration.”

Already on the Water

It sounds like a science fiction novel. Nevertheless, scores of these hulls are already in service, filling myriad roles. One firm has been putting autonomous solutions on the water for many years. ASV Global’s chance said in August, “We have delivered more than 100 new build USVs; about 10x that of our nearest competitor in the diesel-powered category. We have also converted 15 manned vessels to optionally unmanned and integrated more than different 40 payload types.”

Even with that success, ASV isn’t sitting on its hands. Their recent collaboration with Metal Shark is a perfect example. Chance explained, “Metal Shark is a leader in the small to mid-sized security vessel industry, headquartered just 30 minutes down the road from ASV Global’s US headquarters. The combination of ASV Global’s autonomous control technology and Metal Shark’s line of patrol craft make for a powerful solution.”

To date, 60 percent of ASV Global’s unmanned sales are defense-oriented, with the balance in the commercial arena. Already deeply immersed in Europe’s most advanced mine countermeasure program, Chance also admits, “It is a bit of a challenge to predict where the next big thing will likely hit as there are many areas, both military and commercial, that are poised to capitalize on our game changing technology.”

Conventional wisdom says that the arrival of autonomous vessels in the workboat sectors will be far easier to digest than that which might be planned for the 1,000 foot boxship. DNV GL's Ørbeck-Nilssen is measured in his approach to what might come next. “I think we should first of all start by clarifying that there is a big difference between autonomous shipping, autonomous vessels, and unmanned vessels. Autonomy and high degrees of autonomy make a lot of sense because you will have more information coming to you from sensors placed on various sorts of equipment … And having that information, you will be able to a certain degree to reduce, for instance, the number of officers attending the engine room. Maybe for a tanker, we have four officers, you could possibly reduce that to three or two officers. That is not unmanned, but that is a high degree of automation which makes sense.”

DNV GL's Ørbeck-Nilssen

DNV GL's Ørbeck-Nilssen

Ørbeck-Nilssen continued, adding, “Unmanned vessels – that’s a completely different story and I would say that it’s not likely to happen because you have equipment on board that needs maintenance, you’ll still need for emergency situations to have people there to be able to respond, so that will be maybe for the very niche applications. We will see some, say, highly autonomous maybe even unmanned vessels, but again, this is more for niche applications.”

The Changing Workforce

Once just a vision, the autonomous vessel is here. What that means for labor is another thing altogether. ASV’s Chance discounts the ultimate impact, saying, “The dirty little secret of the unmanned boat business is that it is not completely unmanned. We have talked about reduced manning, bridge aids on manned vessels, and about manning unmanned ships as they come in and out of port. There is also the maintenance of the vessels once in port. My guess is that the natural attrition of mariners due to retirement will more than offset the jobs lost due to automation.”

Another firm at the heart of this rapidly developing business is Rolls Royce. Oskar Levander, Rolls Royce Vice President of Innovation, Engineering and Technology, asked recently, “Given that the technology is in place, is now the time to move some operations ashore? Is it better to have a crew of 20 sailing in a gale in the North Sea, or say five in a control room on shore?” But, while some firms focus on technologies, Lloyds Register (LR) tackles manning issues, and emphasizes changing seafarer skill sets.

In a report published in 2015, IACS member LR in conjunction with UK-based QinetiQ , and the University of Southampton, all say, “There are over 104,000 ocean-going merchant ships. The shortage of highly-qualified sea-going staff is an increasing concern, especially as ships become more complex due to environmental requirements.”

As most radio officers are now considered archaic, job qualifications continue to evolve. The report also offers, “While new technology will create the demand for new skills, the smart ship efficiencies achieved may render some maritime professions obsolete, as with other technological evolutions. Only time will tell if the net effect will be positive or negative.” Earlier this year, outgoing IACS Chairman & DNV GL Maritime CEO Knut Ørbeck-Nilssen also shared his outlook on autonomous vessels. As stakeholders leverage technology, one inevitable outcome is that fewer mariners will be needed. Reduced manning has always been a sore spot with North American labor unions. Leaving the labor aspect aside, the question of shipboard maintenance is of paramount concern. Not necessarily so for Ørbeck-Nilssen. “You will always have people on boats because of required maintenance. If you project five to ten years into the future, the systems will become gradually more complex because we are combining software and physical systems, so these cyber physical systems will be more and more demanding for seafarers to cope with.” This, says Ørbeck-Nilssen, will require a much closer connection with shore operations. If so, tomorrow’s mariner will be a much different person.

“Naturally, seafarers will have to also change some of the competencies that they have, and be able to deal with shore organizations, and some of these more complex systems.”

Metal Shark’s Josh Stickles provides a different perspective. “You can sum it up well with ‘dull, dirty, and dangerous.’ However, a fully-autonomous solution isn’t required in all cases. Crew reduction is a key capability of our technology as it exists today. Autonomous capability also allows for operations to become less weather-dependent. The result is reduced operating cost, loss of human life, and also a significant reduction in the long term health issues associated with extended time at sea.”

With many stakeholders hesitant to couch autonomy in terms of mariner head count, its impact on marine business going forward cannot be denied. That said; autonomy creates other jobs that will displace more traditional seafaring roles. Stickles continues, “We agree and we haven’t been shy about saying so. The largest and most immediate potential impact of this technology is crew reduction and in some cases elimination.

How much safer and more effective could we as an industry be if we could reduce the risk and loss of human life while performing our missions more efficiently? Imagine, for example, if a fleet of quickly-deployable, autonomous firefighting vessels existed during the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Such vessels could be sacrificial if necessary, to get in closer than humanly possible to deliver maximum firefighting force. Then, imagine fleets of inexpensive and quickly deployable oil skimmers and boom boats, working around the clock.”

Tech-based developments don’t provide the panacea for all problems. Indeed, one promising application for autonomous workboats is for spill response missions. For example, two emerging issues have spill response managers concerned. First, experienced personnel are leaving the field and recruitment is difficult. Secondly, spill prevention presents a downside: businesses can’t stay in a field if there’s no work.

Devon Grennan, SCAA’s president and CEO and President of Seattle-based Global Diving & Salvage had this to say: “We have tenured professionals exiting the industry faster than the next generation can gain experience.”

Devon Grennan, SCAA’s president and CEO and President of Seattle-based Global Diving & Salvage had this to say: “We have tenured professionals exiting the industry faster than the next generation can gain experience.”

The Spill Control Association of America (SCAA) keeps a close eye on these developments. Devon Grennan, SCAA’s president and CEO and President of Seattle-based Global Diving & Salvage had this to say: “We have tenured professionals exiting the industry faster than the next generation can gain experience.” Because of that, SCAA has a Future Environmental Leaders committee focusing on recruitment. Autonomous vessel providers, of course, might just have another equally appealing solution.

Looking Ahead

Just as advances in waterborne shipping – for more than 50 years – could only be measured in the size of the tonnage being produced, so too will the ship of the future be measured by the number and quality of bells and whistles that make it float. Vince den Hertog, RAL’s Vice President of Engineering, takes a measured approach. “Philosophically, we are also on the same page as far as setting realistic expectations for our clients and ourselves. We see autonomy being an incremental process and are both focused on practical solutions using best available technology, not autonomy for its own sake within a more futuristic vision.”

Sea-Machines CEO Michael Johnson has his own vision. “I want stakeholders to know that autonomous is not synonymous with unmanned. While companies like Rolls Royce are projecting about the unmanned ships of the future, we see it somewhat differently and foresee a world where autonomous control increases the capability, safety, and productivity of manned ships.”

Whatever your take on autonomous vessels, it isn’t too late to get on board. But, you might have to wait until the next port call to do so. That’s because, without a doubt, ‘that ship has already sailed.’

Read Work‘bots’: Autonomous Vessels Arrive in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of November 2018 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from November 2018 issue

Content

- The Forward-Facing Coast Guard page: 10

- U.S. Flag Vessel Safety page: 12

- Preventing Maritime Vessel Explosions – The Role of the Marine Chemist page: 16

- Software Solutions: Communicate or Stagnate page: 20

- Joey Farrell: Born to Marine Salvage page: 28

- Work‘bots’: Autonomous Vessels Arrive page: 34

- Shipyards: FMG & its Quest to Build USCG Icebreakers page: 44

- Interview: Admiral Karl Schultz, Commandant, United States Coast Guard page: 46

- Interview: Shuichi Iwanami, Commandant, Japan Coast Guard page: 54

- AET Grows in Brazil page: 60

- Shipyard Report: Abeking & Rasmussen page: 66

- Shipyard Report: Detyens Shipyards page: 70

- Water Backed Welding & Fixing FPSOs page: 74