WTC Clean-Up: Getting down and dirty

The enormity of the September 11 terrorist attacks on the U.S. have effectively changed the world's collective attitude toward security, particularly in regards to the potential use of the maritime industry as an instrument of destruction.

While the events of early September are global in scope, they are also an intimate local affair. As the New York area continues the gargantuan clean-up task, Don Sutherland reports on the maritime industry's role in helping out.

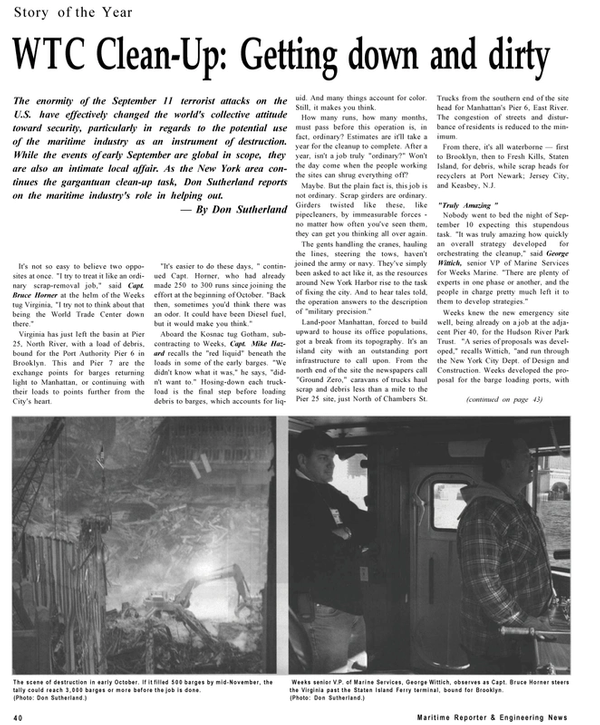

— By Don Sutherland It's not so easy to believe two opposites at once. "I try to treat it like an ordinary scrap-removal job," said Capt.

Bruce Horner at the helm of the Weeks tug Virginia, "I try not to think about that being the World Trade Center down there." Virginia has just left the basin at Pier 25, North River, with a load of debris, bound for the Port Authority Pier 6 in Brooklyn. This and Pier 7 are the exchange points for barges returning light to Manhattan, or continuing with their loads to points further from the City's heart.

"It's easier to do these days, " continued Capt. Horner, who had already made 250 to 300 runs since joining the effort at the beginning of October. "Back then, sometimes you'd think there was an odor. It could have been Diesel fuel, but it would make you think." Aboard the Kosnac tug Gotham, subcontracting to Weeks, Capt. Mike Hazard recalls the "red liquid" beneath the loads in some of the early barges. "We didn't know what it was," he says, "didn't want to." Hosing-down each truckload is the final step before loading debris to barges, which accounts for liquid.

And many things account for color.

Still, it makes you think.

How many runs, how many months, must pass before this operation is, in fact, ordinary? Estimates are it'll take a year for the cleanup to complete. After a year, isn't a job truly "ordinary?" Won't the day come when the people working the sites can shrug everything off?

Maybe. But the plain fact is, this job is not ordinary. Scrap girders are ordinary.

Girders twisted like these, like pipecleaners, by immeasurable forces - no matter how often you've seen them, they can get you thinking all over again.

The gents handling the cranes, hauling the lines, steering the tows, haven't joined the army or navy. They've simply been asked to act like it, as the resources around New York Harbor rise to the task of fixing the city. And to hear tales told, the operation answers to the description of "military precision." Land-poor Manhattan, forced to build upward to house its office populations, got a break from its topography. It's an island city with an outstanding port infrastructure to call upon. From the north end of the site the newspapers call "Ground Zero," caravans of trucks haul scrap and debris less than a mile to the Pier 25 site, just North of Chambers St.

Trucks from the southern end of the site head for Manhattan's Pier 6, East River.

The congestion of streets and disturbance of residents is reduced to the minimum.

From there, it's all waterborne — first to Brooklyn, then to Fresh Kills, Staten Island, for debris, while scrap heads for recyclers at Port Newark; Jersey City, and Keasbey, N.J.

"Truly Amazing " Nobody went to bed the night of September 10 expecting this stupendous task. "It was truly amazing how quickly an overall strategy developed for orchestrating the cleanup," said George Wittich, senior VP of Marine Services for Weeks Marine. "There are plenty of experts in one phase or another, and the people in charge pretty much left it to them to develop strategies." Weeks knew the new emergency site well, being already on a job at the adjacent Pier 40, for the Hudson River Park Trust. "A series of proposals was developed," recalls Wittich, "and run through the New York City Dept. of Design and Construction. Weeks developed the proposal for the barge loading ports, with benefits of water transport over land transport.

We had multiple solutions, including our own fleet of tugs, barges, and cranes." Company literature tells us "by the mid 1930s, scrap iron became the main business of Weeks ... " so besides equipment, Weeks also knew who to talk to. "We proposed that Weeks put out the solicitations to the steel recyclers." But before barges could be loaded, the area around Pier 25 needed more depth. "The dredging permit was issued in 45 minutes," Wittich recalls, "and the first emergency dredging commenced on September 13th.

Around the 21st, sufficient dredging was completed at Pier 25, and the site began developing into what you see today." Today, two giant Weeks cranes dominate the bulkhead. A Clyde Model 28 Gantry crane was chosen for its ability to move & turn quickly, in repetitive actions required for transferring material from shore to barge. Also at the site, a smaller Diesel Clyde, able to work within the tight confines of the available area.

Another Weeks Clyde Model 28 and a Clyde Mod. 24 stevedoring crane work the East River site. The abrupt appearance of such a massive crisis also required the support of other contractors, including Great Lakes Dredge & Docks for dredging around the Pier 6 area in Manhattan, Donjon Marine as well as Kosnac for towing services, and Moran with its own contracts for the operation.

How many other marine contractors and subcontractors, how many truckers, how many guys with torches at the WTC site found themselves sucked into the operation without forewarning?

Wittich reports that most crews work 12-hour shifts, and operations proceed 24/7. But an accurate final head-count probably escapes tabulation.

A sense of scale comes out of Weeks' own appraisal of work to-date. By November 20, the company had offloaded "in excess of" 26,000 trucks. In their own or Dept. of Sanitation barges, they'd transported nearly 100,000 tons of structural steel and 200,000 tons of debris. This had taken some 500 barge loads so far.

Not Always Clockwork "It's on the inside again," said Capt. Hazard aboard the Gotham, finding his next load boxedin by other barges at Brooklyn's Pier 6. What follows is like a 15-puzzle on a giant scale, as captain and crew decide which barges to move, in what order, to reach the designated load. These are cramped quarters, and East River currents are never much fun. But the path is carved smoothly, with hardly a bump.

You'd need a crystal ball, of course, to predict which barges, destined for where, reach Pier 6 when. Wittich cites 400 trucks offloaded on an average day at the Pier 25 site, twice that on heavy days. At times, one or two trucks may arrive, at other times they line-up for blocks. A steady stream can't be expected from the WTC site — it's tough work down there, and still plenty dangerous. It takes patience, flexibility, and a lot of cooperation to make the whole thing work.

"It was phenomenal the way everyone came together," said Wittich. "The City, State, and Federal agencies, and a lot of contractors that are often fierce competitors — everyone worked together. Everyone understood it's a big job, a tough one, and at the base of it all, a tragic one.

But everyone is united by the urgency to get it done." That's something to think about, too. "If the terrorist agenda was to break us apart," said Wittich.

"Make us scared, send us running in panic — then they failed miserably. We became united — more than we were before."

Read WTC Clean-Up: Getting down and dirty in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of December 2001 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from December 2001 issue

Content

- Northrop Grumman, NNS Agree To Merge page: 4

- Wind Power Comes of Age page: 8

- Port Security Legislation Reinforces Security page: 10

- New & Notable page: 14

- Joint Venture Commissioned Into U.S. Military Service page: 15

- Halter Receives Outstanding Rating From U.S. Navy page: 15

- MAAG Gear Wins Large Order For Five CODAG Gear Units In Spain page: 16

- Royal Caribbean's Adventure of the Seas Arrives In N.Y. Harbor page: 19

- Meyer Werft Delivers First of Two to Norwegian Cruise Lines page: 21

- $6 Billion Dollar Merger Tightens Cruise Industry page: 22

- Williams Named President, C O O Of Royal Caribbean And Celebrity Cruises page: 24

- AMCV Demise Sinks U.S. Cruise Building Hopes For Now page: 25

- Great Ships of 2 0 0 1 page: 26

- Bollinger Announces New Contracts at Workboat Show page: 39

- WTC Clean-Up: Getting down and dirty page: 40

- Intelligent Software Agents for Machinery Diagnostics page: 47