The First Voyage of the S.S. Michael Moran

I first went aboard the S.S. Michael Moran in the middle of August, 1944, while she was still in the shipyard in Portland. Me. where she was built. She was operated by Moore McCormack Lines, a company with whom I had sailed before. I signed on as Third Mate; this would be my fourth Liberty Ship.

From Portland we sailed down to Boston where we loaded military cargo for a destination unknown.

Most of the crew were down-easters.

Capt. George Blanthorn was Master, a real gentleman with a good sense of humor. The First Mate was a Mr.

Marshall, an older man who had flown with the French Escadrill in WWI. The Second Mate was Mr. Pease.

I can still picture some of the rest of the crew; the Radio Operator and some of the engineers; but. I have long since forgotten their names. I remember that the Third Engineer came from Kleinsfeltersville, Pa. Its claim to fame being that that was the longest name on a post office in the U.S. His claim, not mine. (It's funny what one remembers after 60 years.) For the purpose of camouflage, all ships were painted battleship grey; company colors stowed for the duration.

However, we were not long out of Boston when our good Captain, an old Moore McCormack company man. had the Mate paint the three inch band around the stack dark green and on either side the Mormac logo, a circular, white background with a red "M" in the center. He also had the Mate stencil the name "Little Mike" on the bow of each of our four lifeboats. I never sailed with another skipper who was that audacious.

We were in a pretty good size convoy as we headed out across the Atlantic; 50 to 70 ships or more. By this time, the submarine threat had diminished to some extent and I don't recall any incidents other than some depth charges being dropped on the other side of the convoy. There was a Midget Carrier in the column next to us. They carried a couple of Bi-planes which would take off every morning to reconnaissance the area for submarines and raiders.

Our first landfall was Land's End, England and we were the first convoy to take this route through the English Channel since the beginning of the war.

We proceeded up the channel to Southend, located at the mouth of the Thames River which leads to London.

There we dropped anchor, awaiting orders.

We were there several days before we received orders to proceed, in convoy, to Methil, Scotland, which is near Edinburgh. There we dropped anchor and again waited for orders.

It was several days before we were told to join another convoy that was heading south to Southend. This was the period when the Allies were about to take Antwerp and the powers weren't sure where our cargo was most needed. We made this trip up and down the coast several (maybe four) times, before we were finally ordered to Cherbourg, France.

We were in Cherbourg about a week while the ship was being discharged. The city had sustained a lot of damage from the Nazi bombers and we were discouraged from going ashore during the day. After dark, when there was total blackout, no one was allowed to go ashore. (The Third Assistant from Kliensfeltersville and I snuck ashore one night and almost got into a heap of trouble. But, that's another story!) From Cherbourg, we were sent across the Channel to Our Supporters ... Then and Now Fowey (pronounced "Foy"), on the southeast coast of England, where we loaded a full cargo of china clay.

Fowey is an ancient seaport village with cobblestone streets and stone buildings. It has a very small harbor and our ship took up most of it. To get us to the loading dock, they used a couple of small tugs to turn us around in the harbor and then they towed us, stern first, up the river to the loading dock.

From Fowey, we headed south towards Land's End where we were to meet up with a convoy.

And this is where the fun begins.

Formation in the Fog As we approached Land's End, the fog started to settle. Patches at first, growing thicker as the day went on. The convoy was about the same size as the one coming over so we had all those ships trying to form up into rows and columns.

Convoy formation was always a dicey operation, with ships going in all directions trying to get into position. Remember, this was before radar, so the Captain's world was what he could see from the wing of the bridge, one side at a time, and there were many near misses and lots of whistle blowing.

Different size ships; different kinds of engines: differ- ent flags speaking different languages all contributed to a challenging experience in good weather; a chaotic experience in the fog or rain.

We had fog the entire journey, and basically, the practice in convoy was to follow the ship ahead while keeping a check on the compass course of the convoy.

At night, all ships were completely blacked out, with the exception of a small blue light on the stern that could only be seen from directly behind the ship. This was what the helmsman tried to steer by.

During the day. each ship towed a fog buoy about five hundred feet astern.

This was a very simple device consisting of two pieces of wood bolted together in the shape of a cross. About a two inch hole was drilled down the center from which a length of pipe extended.

On the underside, a small piece of sheet metal was attached to form a scoop. As this was towed through the water, it ejected a plume of water that was clearly visible and this was the guide for the ship astern.

A lookout was stationed on the bow. it was his job to keep that buoy in sight.

Very often it could not be seen from the bridge. If he saw the ship was lagging behind, or getting to close, he would call the bridge on the sound powered telephone.

However, there was one minor drawback to the fog buoy: it looked very similar to a periscope cutting through the water. There were tales of fog buoys being blown out of the water ... by their own ships. The voyage proceeded without incident to Philadelphia where I signed off the ship on December 12, 1944. End of Voyage One.

We know from "Liberty Ships. The Ugly Ducklings of World War II". by John Gorley Bunker, that the Michael Moran went on to make four more voyages.

one of which she ventured around the world, before she was laid up at New Orleans in 1946. In 1958. she was towed into the Atlantic where she was used as a target for testing new Navy missiles. Her remains now create a fish haven resting on the bottom of the sea.

A good ending for a good ship.

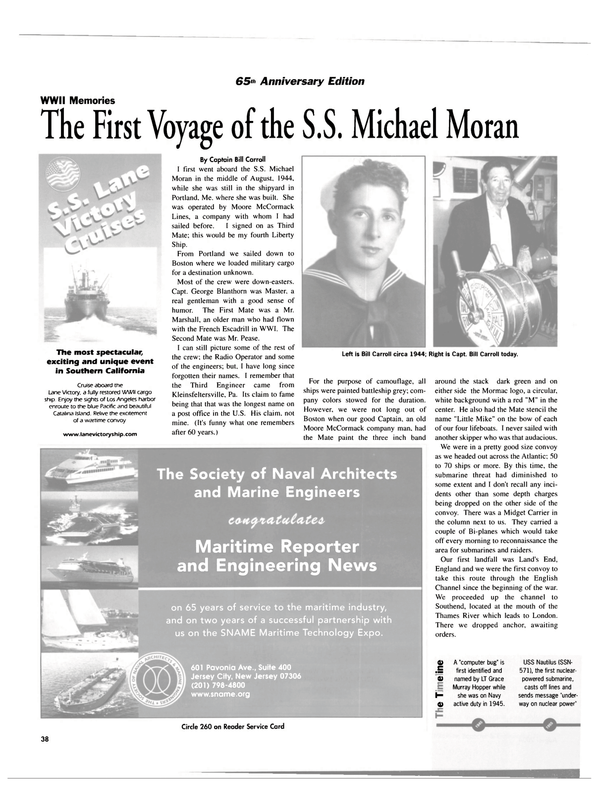

The preceding was written by Captain Bill Carroll. Captain Carroll was kind enough to write to us in response to the February 2004 "Leading Off" piece about the Michael Moran. He was the Third Mate on the ship when it came out of the yard in Portland. Maine in 1944.

Today. Captain Carroll is Master of the S.S. Lane Victory, one of the last operating Victory Ships from WWII and now a National Historical Monument, berthed in San Pedro, Ca. http.V/www.lanevictory.

org

Read The First Voyage of the S.S. Michael Moran in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of August 2004 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from August 2004 issue

Content

- All Dressed Up ... page: 7

- Shipyard Responsible For Poor Construction page: 9

- Dredge Vssel Exception Interpreted page: 10

- Damen Delivers Three ASD Tugs to Kenya page: 12

- IZAR Manises Tests, Delivers Mitsubishi Engine page: 13

- Declaration of Security page: 14

- Flying High Again page: 20

- Subsea7: Staying Connected with CapRock page: 22

- Stolt Offshore Completes Platform Salvage page: 23

- Training and Education in the Maritime Industry page: 24

- A U.S. Coast Guard Mission Since 1917 page: 28

- The Tugboat, Towboat and Barge Industry page: 30

- From 2D CAD to the Integrated Product Model page: 34

- The First Voyage of the S.S. Michael Moran page: 36

- U.S. Coast Guard: Dogged by a Unique Past page: 48

- 2004 SNAME Set for Washington, D.C. page: 49