IS IT TIME TO TAKE THE PUBLIC SHIPYARDS PRIVATE?

Naval shipyards have been in operation in the U.S. for over 180 years and, with the private sector, share the mission of providing adequate naval and maritime resources to meet national defense requirements in times of peace and conflict. These shipyards both built and repaired naval ships until 1967, when, after it was estimated that naval shipyard building costs were about one-third higher than private yard costs, Congress mandated that all future construction be done by the private sector.

Three years earlier, also for reasons of economy and to provide additional work to the private sector during a downturn period, Congress had directed that at least 30% of the Navy's ship overhaul and repair work be allocated to private yards.

This combination of actions reduced government-owned facilities to the eight shipyards now in operation.

The status and prospects of the U.S. shipbuilding and ship repair industry, current political economics and the interests of national defense strongly suggest that it is now time to take the next important step in the evolution of the industry: privatization of the governmentowned shipyards. Among the many strong arguments favoring this action, economy is still a major consideration.

Naval shipyard operating costs are still well above those of the private sector (industry sources estimate they are about 30% higher), making the yards marginally productive in the performance of their mission. Equally important, however, the majority of private shipyards, although more innovative, technologically superior and cost efficient than ever before, are suffering from lack of work and many face closure, jeopardizing the shipbuilding mobilization base essential to national security.

Furthermore, privatization of government shipyards would be in keeping with the current political philosophy that any activity that government cannot do better than the private sector should be divested or contracted out to industry.

In assessing the merits of such an action, a good place to start is with the 1984 Annual Report of the Coordinator of Shipbuilding, Conversion and Repair, Department of Defense, which fully describes the status of the Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Industry of the United States.

Productivity and Efficiency Challenges Met In a preface, the Coordinator, Vice Admiral E. B. Fowler, Commander, Naval Sea Systems Command, states that the Navy and industry have successfully met the challenges posed by the Navy's plan to build a 600-ship fleet by the 1990s: "The Navy, as the manager of the program, was challenged to assure that proper quality and cost effective ships were delivered in a timely manner. The shipbuilders were challenged to increase productivity and efficiency through innovative planning, modernization and effective utilization of their assets.

"The Navy and the industry have responded positively to these challenges. Progress in the areas of increased competition and improved Navy contractor understanding have been particularly noteworthy.

"For its part, the industry is effectively executing the expanded naval construction program and responding to an increase in the numbers of complex naval ship overhauls and selected restricted availabilities. The industry has clearly demonstrated its capacity to support projected military ship construction and repair programs." The scope of this challenge has been enormous, requiring extensive worker training, the application of modern engineering and production methods and large capital investments in facility modernization.

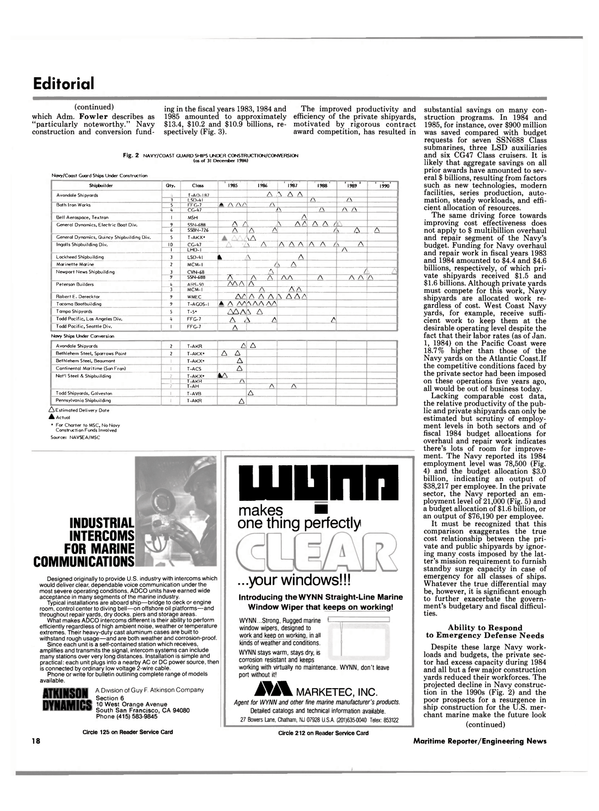

During 1984, 58 private shipyards were engaged in Navy work: ten performing new construction and conversion, 39 performing overhaul and repair work, and nine providing all four services (Fig. 1). These operations were engaged in constructing 91 ships for the Navy and nine for the Coast Guard, as well as converting 13 ships to Navy use (Fig. 2). In addition, 348 service craft, special warfare craft and standard landing craft were delivered to the Navy, part of 37 separate programs to produce 597 craft and vessels for the Navy, Marines and foreign navies .

Increased Competition The Navy annual report gives details on the benefits of increased competition for contract awards which Adm. Fowler describes as "particularly noteworthy." Navy construction and conversion funding in the fiscal years 1983,1984 and 1985 amounted to approximately $13.4, $10.2 and $10.9 billions, respectively (Fig. 3).

The improved productivity and efficiency of the private shipyards, motivated by rigorous contract award competition, has resulted in substantial savings on many construction programs. In 1984 and 1985, for instance, over $900 million was saved compared with budget requests for seven SSN688 Class submarines, three LSD auxiliaries and six CG47 Class cruisers. It is likely that aggregate savings on all prior awards have amounted to several $ billions, resulting from factors such as new technologies, modern facilities, series production, automation, steady workloads, and efficient allocation of resources.

The same driving force towards improving cost effectiveness does not apply to $ multibillion overhaul and repair segment of the Navy's budget. Funding for Navy overhaul and repair work in fiscal years 1983 and 1984 amounted to $4.4 and $4.6 billions, respectively, of which private shipyards received $1.5 and $1.6 billions. Although private yards must compete for this work, Navy shipyards are allocated work regardless of cost. West Coast Navy yards, for example, receive sufficient work to keep them at the desirable operating level despite the fact that their labor rates (as of Jan.

1, 1984) on the Pacific Coast were 18.7% higher than those of the Navy yards on the Atlantic Coast.If the competitive conditions faced by the private sector had been imposed on these operations five years ago, all would be out of business today.

Lacking comparable cost data, the relative productivity of the public and private shipyards can only be estimated but scrutiny of employment levels in both sectors and of fiscal 1984 budget allocations for overhaul and repair work indicates there's lots of room for improvement.

The Navy reported its 1984 employment level was 78,500 (Fig.

4) and the budget allocation $3.0 billion, indicating an output of $38,217 per employee. In the private sector, the Navy reported an employment level of 21,000 (Fig. 5) and a budget allocation of $1.6 billion, or an output of $76,190 per employee.

It must be recognized that this comparison exaggerates the true cost relationship between the private and public shipyards by ignoring many costs imposed by the latter's mission requirement to furnish standby surge capacity in case of emergency for all classes of ships.

Whatever the true differential may be, however, it is significant enough to further exacerbate the government's budgetary and fiscal difficulties.

Ability to Respond to Emergency Defense Needs Despite these large Navy workloads and budgets, the private sector had excess capacity during 1984 and all but a few major construction yards reduced their workforces. The projected decline in Navy construction in the 1990s (Fig. 2) and the poor prospects for a resurgence in ship construction for the U.S. merchant marine make the future look chant marine make the future look bleak for the industry and its ability to adequately meet national security needs. Admiral Fowler expressed this concern: "Despite these positive aspects, I must note the Navy programs currently provide most of the workload of the shipbuilding and ship repair industry. The commercial shipbuilding market is providing little opportunity for U.S. shipbuilding business. There is evidence that the U.S. industry is trending towards that level required to support Navy programs.

"In this environment, the more competitive and efficient shipyards are continuing to win Navy business while the total number of yards is decreasing.

"With the number of facilities decreasing, I am concerned about the ability of the shipbuilding and repair industry to respond to an emergency requirement for a major and rapid maritime buildup.

Legislative initiatives that are underway could provide the environment for the industry to achieve this capability. These efforts must be vigorously supported." During 1984, ten of the shipyards having Master Repair Agreements with the Navy closed, leaving 141 active at year end. Since then, another three have closed, two have entered Chapter 11 and one merger has occurred. Some of these recent casualties have involved shipyards with both Navy construction and repair capabilities that were included in the Active U.S. Shipbuilding Base, which is considered to contain the minimum capacity needed to provide adequate mobilization capability for defense requirements.

This base was comprised of 24 shipyards in 1984 (including one in Chapter 11 and one with no employees), compared with 26 in 1980 (Fig. 6). It should be pointed out that adequate mobilization capability means not only the construction and repair of naval combatants, auxiliaries and sealift ships, but greatly increased numbers of trans- ports needed in a prolonged conflict but which no longer exist in the U.S.

merchant marine fleet.

Declining shipyards correlate to declining workloads which emphasizes the current importance of Navy overhaul and repair work to the private sector. And as Navy construction work declines towards the end of this decade, its importance will become even greater.

Initiatives to Maintain Maritime Resources Adm. Fowler suggests there are legislative initiatives under way that could provide the environment for private industry to achieve the ability to respond to an emergency requirement for a major and rapid maritime build-up, and that "these efforts must be vigorously supported." These include such actions as cargo preference laws, a maritime redevelopment bank, restoration of construction differential subsidies and provision of Title VII funds for passenger car shipping vessels.

Nothing presently before the Congress, however, could have as positive impact on the private sector's stability and well-being as the initiative of privatizing the public shipyards. It would almost immediately channel $ billions of additional work into these facilities and halt the dangerous trend now gaining momentum.

A practical approach would be to sell the two shipyards (Long Beach, CA and Philadelphia) that do not have a nuclear power servicing capability to private industry on a competitive bid basis. The remaining six facilities (Portsmouth, NH; Norfolk, VA; Charleston, SC; Mare Island, CA; Puget Sound, WA; and Pearl Harbor, HA) would remain under government ownership but be managed under government-owned/ contractor-operated (GOCO) agreements.

Private industry would compete for these GOCO contracts which could be written to contain profit incentive and revenue sharing provisions.

The Benefits of Privatization There would be many advantages to this course of action: 1) Work performed by private yards generates taxes, whereas work performed by public yards is paid entirely by taxes on the general public.

2) The need to keep shipyard facilities and operating methods up to date technologically is fueled by the competitive market system. This dynamic does not prevail in government- owned operations which are protected from the rigors of price and demand interactions.

3) Savings realized by the Navy on repair work could be spent on alternate products and services, or used in other high priority government programs.

4) By eliminating government functions and facilities redundant to those of the U.S. Shipbuilding Industry, the prospects for balancing the federal budget would be enhanced.

5) The government's capital investment in the facilities could be partially recouped. In addition, pension and other liabilities could be phased out over a measurable period of time through normal attrition and transfer to the private sector.

6) By obtaining more and better naval and maritime products and services per dollar, the U.S. taxpayer would be better served.

7) The essential shipbuilding mobilization base, which has proven invaluable in past emergencies and conflicts, would be maintained at least cost to the taxpayer and at peak efficiency for the Navy.

Other Considerations Privatization would, of course, require certain guarantees and agreements, between government and industry to cover sensitive areas.

These would include: 1) The means whereby legal disputes over excess costs, such as occurred in the 1970s, could be minimized and quickly adjudicated.

2) Assurance that the Navy's needs would have priority over commercial work.

3) The negotiation of labor and management agreements that would be compatible with national security and defense requirements.

Privatization is an option that should be carefully considered and acted upon. Such an action need not be disruptive to the U.S. shipbuilding industry which, as a vital defense resource, must be allowed to meet its commitments without constraint or interruption. A wellplanned, phased approach to the effort, combined with positive government/ industry cooperation, could certainly overcome potential difficulties and, at the same time, minimize job losses, maintain Navy delivery and work completion schedules and result in a more cost effective operation, thereby creating a stronger defense posture.

Read IS IT TIME TO TAKE THE PUBLIC SHIPYARDS PRIVATE? in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of February 1986 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from February 1986 issue

Content

- Bremer Vulkan To Build 2 Bremen Class Frigates For Federal German Navy page: 5

- Study To Evaluate Tanker-Based FPSO For Gulf Of Mexico page: 5

- Marinette Marine Delivers Last Of 52 Workboats A Year Ahead Of Schedule page: 6

- Boston Fuel Acquire Assets Of Boston Towboat Co. page: 7

- M.A.N.-GHH To Build Floating Drydock For Polish Shipyard page: 7

- British Broker Reports Surge In Tanker Rates, Fall In Laid-Up Tonnage page: 7

- Robert E. Derecktor Launches First Of Two Staten Island Ferries page: 8

- Beth-Sparrows Point Yard Installs $1.1-Million Intermediate Gate For Building/Vessel Servicing Basin page: 8

- New Names Announced For Wartsila Diesel Units page: 9

- HIAB-FOCO Delivers Two Service Cranes To North Sea Oil Project page: 9

- Bath Iron Works Launches Its First Aegis Cruiser page: 10

- Water Jetting System To Install Steel Pilings Developed By Navy page: 11

- USCG And ASNE Flagship Section Sponsor Patrol Boat Symposium page: 12

- Webber Appointed Vice Admiral And U.S. Navy's Chief Engineer page: 12

- Automatic Power Offers 20-Page Color Brochure On Marine Signal Systems page: 12

- Captain Hjelde Named VP And GM At Barber page: 13

- TeleSystems MCS-9100 Receives Japanese Type Acceptance page: 13

- IS IT TIME TO TAKE THE PUBLIC SHIPYARDS PRIVATE? page: 16

- UPDATE ON FY 1986 NAVY PROGRAMS page: 26

- Navy Contracts Totaling $629.2 Million Awarded To Bath And Ingalls Yards page: 30

- Peterson Builders Delivers ARS-51, Grasp, To Navy page: 31

- 1986 Apelco Full-Color Product Catalog Available page: 34

- Carnegie Hero Medals Awarded Posthumously To Fournier, Govoni page: 34

- Coast Guard And Navy To Hold Joint Fire Research Program page: 35

- Peterson Builders Receives Navy Certification Of Metal Spray Facility page: 35

- Key Appointments At Oerlikon page: 36

- NICOR Consolidates Administrative Functions Of 2 Marine Subsidiaries page: 36

- BP Offers Free 32-Page Brochure On World Energy page: 37

- ASEA Names Jon Turley Manager Marine Offshore page: 37

- New One-Stop Shopping Sensors And Controls Catalog From Transamerica Delaval page: 38

- Marine Machinery Association To Sponsor Navy/Industry Panel Discussions On Feb. 26 page: 38

- The New 710G Series Diesel Engines From General Motors Electro-Motive Division page: 40

- Todd Ceases Operations At New Orleans Division page: 41

- Marine Travelift Introduces New Floating Boat Hoist Design page: 41

- Puroflow Filters To Protect Sperry Computers page: 42

- Texas Instruments Offers New GPS Software page: 43

- Aegis Missle Cruiser Valley Forge Commissioned At Ingalls Yard page: 44

- New Yard Opens In Port of Altamira page: 47

- Jacques Cousteau Receives Testimonial Plaque From Carrier Transicold Employees page: 47

- Vecom Takes Over Marine Division Of Houseman page: 48

- Caterpillar Offers Literature On New Marine Diesel Propulsion System Products And Support Programs page: 49

- New Teleflex Remote Valve Actuators Are Designed To Eliminate Problems And Cut Costs page: 52

- Dr. A.C. Antoniou Joins ASRY Production Team page: 53

- Dillingham Offers Free Full-Color Brochure On Ship Repair Facilities page: 53

- Hempel Introduces 'Damp Steel' Primer page: 54

- Reco Crane Promotes Hardin—Literature Offered page: 60

- Metropolitan Offers New Vanstone Flanged Fittings page: 60

- Meyer Retires As Deputy Commander At NAVSEA page: 60

- American Appoints Monaco New Cordage Engineer page: 61