Impact Of Lifting Alaskan North Slope Oil Export Ban On The U.S. Maritime Industry

G.A.O. Assesses Nation's Energy Security And The Negative Effect On Maritime Industry The Export Administration Act of 1979 places restrictions on the export of Alaskan North Slope crude that effectively ban its export. The act states that "no domestically produced crude oil transported through the Alaska pipeline may be exported from the United States." The purpose of this ban was to restrict "the export of goods where necessary to protect the domestic economy from excessive drain of scarce materials and to reduce the serious inflationary impact of foreign demand." This provision of the law was part of the compromise that permitted the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. The act allows the ban to be lifted only upon the President's certification that the export of Alaskan oil is in the national interest and meets several other specified conditions.

If the ban on exporting Alaskan North Slope crude oil remains in place, Alaskan North Slope production will, of course, continue to go to U.S. ports. However, because of declining Alaskan North Slope production, shipments to eastern U.S.

ports, i.e., those on the East Coast, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico, will probably cease at some time in the next several years.

Producers of Alaskan North Slope crude prefer to sell their crude to West Coast refiners, given the cost of transporting it to East Coast refiners.

If the ban on exporting Alaskan North Slope crude oil is removed, some of it is likely to be exported to Pacific Rim countries. Since transportation costs to Pacific Rim ports are much less than those to eastern U.S. ports, oil that is currently transported to the eastern United States is likely to be exported. In addition, some Alaskan North Slope crude that would have gone to the U.S.

West Coast may also be exported, since the cost of transporting oil to some Pacific Rim destinations is comparable to, if not lower than, the cost to U.S. West Coast ports. In this regard, the heavier weight of Alaskan North Slope crude is more likely to be attractive to refiners in Pacific Rim countries that it is to U.S. West Coast refiners, who refine more of their oil into light products, such as gasoline.

The probable economic effects of lifting the ban on Alaskan North Slope crude (as compared with leaving it in place) will be to • increase the price of Alaskan North Slope crude at the wellhead—because of the reduction in transportation costs and the attractiveness of Alaskan North Slope crude to Pacific Rim refiners—and, consequently, the price that West Coast refiners pay for crude oil; • promote economic efficiency by reducing transportation costs in the Alaskan North Slope crude oil trade, increasing domestic oil production, allowing better use of refinery processing resources, and ensuring that Alaskan North Slope oil is allocated to its highest valued uses; and • accelerate the decline in tanker demandandhurttheU.S. maritime industry because Alaskan North Slope exports are likely to be transported on foreign-flag rather than U.S.-flag tankers.

The energy supply disruption resulting from Iraq's invasion of Kuwait has focused attention on U.S. energy security and, in particular, our reliance on imported oil.

From an energy security standpoint, the effect of lifting the Alaskan North Slope export ban would probably be to increase total U.S. oil imports but possibly decrease net imports (total imports minus exports) to the extent that refinery efficiency is improved and Alaskan North Slope oil production increases in response to higher prices. Finally, lifting the ban could also contribute to the integrated world market's smooth and efficient functioning.

Since 1987, the amount of Alaskan North Slope oil shipped to eastern ports has declined as a result of decreasing Alaskan North Slope production and increasing West Coast consumption. Because transportation costs to eastern ports are considerably higher than those to the West Coast, Alaskan producers sell most of their oil to West Coast refiners.

This trend is expected to continue, so that in the near future Alaskan North Slope crude shipments to eastern ports will cease. The exact timing of this development will depend to a large extent upon the rate of decline of Alaskan production.

Using the Energy Information Administration's (EIA) base case assumption of Alaskan production, shipments to eastern ports could cease by 1992, even if West Coast demand for Alaskan production remains constant.

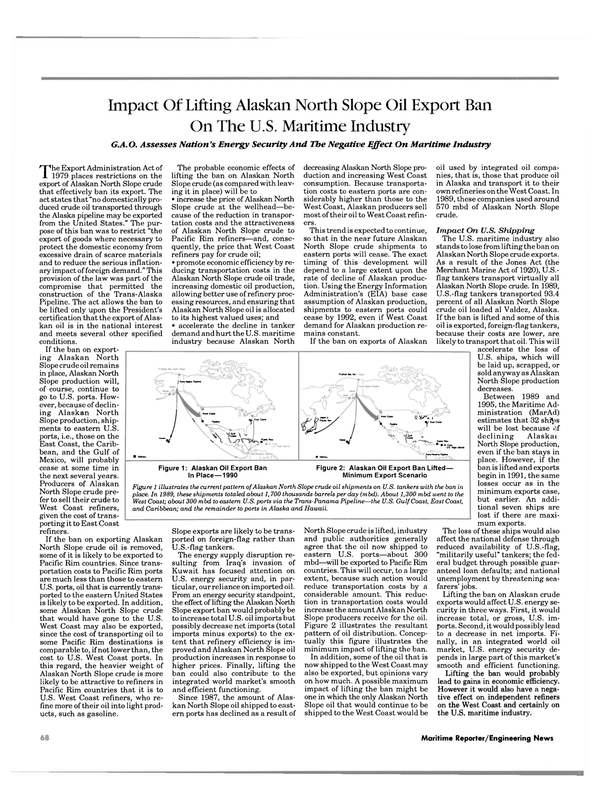

If the ban on exports of Alaskan North Slope crude is lifted, industry and public authorities generally agree that the oil now shipped to eastern U.S. ports—about 300 mbd—will be exported to Pacific Rim countries. This will occur, to a large extent, because such action would reduce transportation costs by a considerable amount. This reduction in transportation costs would increase the amount Alaskan North Slope producers receive for the oil.

Figure 2 illustrates the resultant pattern of oil distribution. Conceptually this figure illustrates the minimum impact of lifting the ban.

In addition, some of the oil that is now shipped to the West Coast may also be exported, but opinions vary on how much. A possible maximum impact of lifting the ban might be one in which the only Alaskan North Slope oil that would continue to be shipped to the West Coast would be oil used by integrated oil companies, that is, those that produce oil in Alaska and transport it to their own refineries on the West Coast. In 1989, these companies used around 570 mbd of Alaskan North Slope crude.

Impact On U.S. Shipping The U.S. maritime industry also stands to lose from lifting the ban on Alaskan North Slope crude exports.

As a result of the Jones Act (the Merchant Marine Act of 1920), U.S.- flag tankers transport virtually all Alaskan North Slope crude. In 1989, U.S.-flag tankers transported 93.4 percent of all Alaskan North Slope crude oil loaded al Valdez, Alaska.

If the ban is lifted and some of this oil is exported, foreign-flag tankers, because their costs are lower, are likely to transport that oil. This will accelerate the loss of U.S. ships, which will be laid up, scrapped, or sold anyway as Alaskan North Slope production decreases.

Between 1989 and 1995, the Maritime Administration (MarAd) estimates that 32 shi^*s will be lost because i f declining Alaskai North Slope production, even if the ban stays in place. However, if the ban is lifted and exports begin in 1991, the same losses occur as in the minimum exports case, but earlier. An additional seven ships are lost if there are maximum exports.

The loss of these ships would also affect the national defense through reduced availability of U.S.-flag, "militarily useful" tankers; the federal budget through possible guaranteed loan defaults; and national unemployment by threatening seafarers' jobs.

Lifting the ban on Alaskan crude exports would affect U.S. energy security in three ways. First, it would increase total, or gross, U.S. imports.

Second, it would possibly lead to a decrease in net imports. Finally, in an integrated world oil market, U.S. energy security depends in large part of this market's smooth and efficient functioning.

Lifting the ban would probably lead to gains in economic efficiency.

However it would also have a negative effect on independent refiners on the West Coast and certainly on the U.S. maritime industry.

Read Impact Of Lifting Alaskan North Slope Oil Export Ban On The U.S. Maritime Industry in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of February 1991 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from February 1991 issue

Content

- Deutz-Powered Cruise Sailing Ship Launched At SFCN Shipyard page: 6

- Vancouver Shipyards Wins $35-Million Contract To Overhaul Ferry page: 6

- AK-WA Converts Incinerator Ship, Wins Contract To Modernize LCMs And Rebuilds Fishing Vessel page: 8

- Application For Use Of Foreign-Flag Vessels By U.S. Operator Receives Close Attention By Both MarAd And Congress page: 10

- Sperry Marine Donates Historic Gyrocompass To Museum page: 11

- Saab's Computerized Cargo Handling System Selected By United Tankers Of Sweden page: 11

- Cummins Marine Diesels Power Fire/Rescue Boat For City Of Avalon page: 12

- NABRICO To Build Four Chemical Barges For Maryland Marine page: 12

- Moran Towing Appoints Three New Vice Presidents page: 14

- Stewart & Stevenson Receives $20-Million Order For Gensets page: 14

- Hampton Roads Complex Poised For Substantial Expansion In 1991 page: 15

- Singmarine Acquires Two Docks To Cope With Increased Work Volume page: 15

- Versatile Pacific Delivers Search And Rescue Vessel To Canadian Coast Guard page: 16

- SNAME And SSC To Sponsor MSIMMS '91 Symposium In Arlington, March 18-19 page: 16

- Bird-Johnson Appoints Peter J. Gwyn New President & COO page: 18

- SpillStop® Technique Prevents Oil Spillqge After Tanker Accidents page: 19

- Los Angeles Shipyard Corporation Looks To Lease Todd Facility page: 20

- Tests Begin On Engine Developed By MAN B&W, SEMT Pielstick page: 20

- Southern Marine Industries page: 22

- Detyens Shipyards Refits 465-Foot Bulk Carrier page: 27

- Sperry Marine Chosen For Japan Corporate Program page: 27

- Sumitomo To Launch $59 Million Double-Skin, Double-Bottomed Tanker page: 28

- Conoco To Increase Spending To $2 Billion In 1991 page: 28

- Aquamaster Brochure Describes Products And Services Offered page: 28

- MARCO-Seattle Yard Busy With Fishing Vessel Construction, Conversion page: 30

- Schuyler Rubber, Marine Fender Firm, Receives Recycling Award page: 30

- COATINGS & CORROSION CONTROL page: 32

- Study Finds No Causal Link Between Crew Size And Maritime Safety page: 37

- Avondale Boat Division To Build 3,900-HP Tug For U.S. Owner page: 38

- Gulf Crisis Confirms Need For Global Naval Force page: 40

- H. LAWRENCE GARRETT I Secretary Of The Navy page: 41

- Navy Announces Ship Repair Schedule For FYs 91-92 page: 44

- VADM. John W. Nyquist Calls For Stable Shipbuilding Budget page: 44

- NAVY SEALIFT SHIP PROGRAM TO INJECT $1.3 BILLION INTO U.S. MARITIME INDUSTRY DEFENSE DEPARTMENT PLANNING 5 YEAR PROGRAM page: 46

- MAJOR NAVY CONTRACTS page: 47

- Lasers For Ship Defense Examined By U.S. Navy page: 52

- Nuclear Sub Launched Using NEI Syncrolift For First Time Ever page: 53

- U.S. Government Awards Ship Repair Contracts page: 53

- USS Chosin Joins Pacific Fleet — 13th Aegis Cruiser By Ingalls page: 54

- A / S Deif Offers Automatic Control For Auxiliary Engines page: 55

- Benmar Offers New Fuel Management System To Commercial Industry page: 55

- PSRY Contractors Complete Busy Year —Literature Offered page: 57

- New Decrees Will Free Brazilian Ship Operators From Previous Regulations page: 59

- Shipbuilders Council Announces 1991 Legislative Agenda page: 60

- Esso international Installs AMOS-D On Board Tanker Fleet page: 60

- Sulzer Diesel Changes Name Following Majority Stock Transfer page: 61

- CANADIAN MARITIME INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION'S 43RD ANNUAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE page: 64

- AT&T Radiotelephone Service Helps Keep In Touch On The High Seas page: 65

- AESA To Build Car/Passenger Ferry For Moroccan Owner page: 66

- World Shipyards Capable Of Producing 'Only 40 VLCCs A Year page: 66

- Drewry Study Concludes Era Of Cheaply Acquired And Run Ships Has Ended page: 66

- Global Maritime Fabricates First Swirling Flow Research Combustor page: 66

- Ship Safety Achievement, Jones F. Devlin Awards Announced By AIMS page: 67

- Impact Of Lifting Alaskan North Slope Oil Export Ban On The U.S. Maritime Industry page: 68

- Bender To Construct Two Jackup Vessels For Work In Gulf Of Mexico page: 69

- Air-Independent Mini-Sub Designed By Thyssen page: 69

- New Diesel Engine Maintenance Tool Brochure Offered By Chris-Marine page: 69

- Avondale Begins Construction Of Cargo Variant Ship page: 70

- Ships Built With Foreign Subsidies Might Face Sanctions page: 70

- Shipbuilders Council Of America Seminar On Ship Marketing, Finance To Be Held February 12-13 page: 70

- Skaarup Announces Personnel Changes page: 71

- Lips Offers New Brochure On Marine Propellers And Steerable Thrusters page: 71

- Offshore Symposium Set For Houston, April 4-5 page: 71

- Trinity Marine To Build Fourth Supply Boat For U.S. Owner page: 72

- Oceaneering Awarded Mobile Offshore Production Systems Contract page: 72

- Marine Industries Northwest Repowers Washington State Ferry page: 72

- Bethlehem Steel Sells Two Ore Carriers To Oglebay Norton page: 73

- Tidewater To Supply 41 Tugs, Barges Under Two Multiyear Contracts page: 73

- Rauma Yards Launches Luxury Cruise Ship page: 73