Bottom Line: It's Not Just A Paint Job

On the surface, the subject of paint seems simple. After all, it's just a paint job, right? For maritime applications, however, beauty is much more than skin deep. The coating of surfaces on ships is a complex combination of materials, chemicals and preparation to combat corrosion and maintain a sharp appearance.

The coatings must wear well in the worst of weather and withstand the most extreme environments. They must last with little maintenance, must be earth friendly and safe for people and other living things, and last but certainly not least, they must be affordable.

The paint job found on a contemporary ship may look the same as that of a ship of several decades ago, when in fact very little is the same.

Combating Corrosion Progress in coatings has been driven as much by environmental concerns as any other factor. Many traditional coatings are no longer acceptable for safety, health and environmental reasons, whether in manufacture, application or the resulting finished surface. Paints and coatings have traditionally been made with solid materials suspended in a solvent (which aids in the application), and leave the solid to bond with the surface when the solvent evaporates. Many chemicals used previously as solvents in paints, such as ketones, xylene, or toluene, are hazardous and no longer used. Lead based paints are also prohibited.

Chromium, a formerly prevalent ingredient in paints such as zinc chromate, is a cancer-causing agent.

Coatings with zinc pollute the water.

Lead, as stated, is poison and leads to serious permanent health problems.

Heavy metals used in coatings are highly toxic. Materials have been used as coatings, such as copper sheathing on ship bottoms. Until recently, copper was thought to be safe, but when many copper clad bottoms are in a harbor, the copper kills the marine life and a sterile marine environment results.

Some new paints are "100 percent solids," which means there is a part A and a part B that must be mixed as a resin and catalyst are mixed to make epoxy. These epoxies are non-volatile, do not cause air pollution and are noncarcinogenic.

Their drawback is that the mixed epoxy is very thick, difficult to apply, and must be used right away.

Another approach is the use of watersoluble paints, similar to latex paints used in homes. The obvious drawback is that these coatings are susceptible to being worn away by water, and the maritime application provides ample opportunity for attack by water. Like the epoxies, the water-soluble paints are not a toxicity problem or an environmental hazard. They are safe to store and use.

Teflon has proven to be an effective non-sticking surface for cooking, and it turns out that barnacles and other marine life don't like to stick to it as much as they do on other surfaces. Teflon coated hulls became an effective way to keep bottoms from fouling, keeping speeds and operating efficacies and economies up and maintenance costs down. But Teflon by itself is not the best anti-fouling coating. Teflon in combination with silicone has proven to be even better, actually repelling water to reduce drag.

"This is an expensive combination," says A1 Daech. a research engineer at the Gulf Coast Region Maritime Technology Center, affiliated with the University of New Orleans. "It costs $35 per sq. ft., and there's a lot of square feet to cover on the hull of a ship. Cost becomes a limitation." Daech sees great promise for lithium as a key ingredient in ship coatings. "It's one of the most common elements. It's the lightest metal, almost a gas," he says.

"Lithium can replace chromium and lead. It's plentiful, and it's environmentally acceptable.

Another new method, Daech says, is electrostatic spraying of paint, involving the spraying of charged particles of plastic onto a negatively charged surface.

The metal surface is then heated to fuse the paint. "The materials are reasonable.

There's a capital investment, but once you've invested in this equipment you can use it for a number of years and amortize it." Daech says electrostatic coating is being used now on components. It creates a tough coating, not unlike baked enamel on cookware.

Teflon, which is being used in some applications on bottoms, repels water.

The water actually beads up. But Daech says that an even better way to reduce friction is to introduce a stream of air between the Teflon and the water. The ship is actually riding on a stream of compressed air, which has less resistance than water.

He also points to alloys that have been upgraded. Stainless steel, and now corrosion resistant steel (CRES), doesn't need to be painted. "You pay an extra capital expense. But it's care free for a long time once it is in place." Ballast Tanks Pose a Challenge All large ships have voids and tanks that are difficult to access and may not be visually inspected for many years, if at all. These closed spaces require coatings that can last for decades without repair.

Ballast tanks can account for up to 45 percent of total painted area on a vessel and are subjected to an "aggressive cargo, namely seawater, as well as wet/dry and warm/cold cycles," says Kent Holm of Sigma Coatings in Denmark.

Pure epoxies are superior to epoxy coatings with cheaper modifying resins (such as coal tar), and they last longer and corrode less. "Pure epoxies perform more consistently throughout the coating's lifetime than modified or coal tar epoxies. Even though pure epoxies can be 20-50 percent more expensive than modified epoxies. cost savings on productivity at new-build, as well as a reduced need for maintenance, will more than make up for the price difference, " says Joey Keasberrv of Sigma Coatings.

The SigmaPrime multipurpose anticorrosive epoxy coating is used for both new construction and maintenance and can be used virtually anywhere, on both internals and external areas.

In water ballast tank surfaces, these pure epoxy coatings are as good as when new a decade later. "Pure epoxies have an expected lifetime of 20-25 years as opposed to modified epoxies. which have a life expectancy of 8-15 years.

Obviously, this very much depends on the application itself. Poor application will reduce the coating's lifetime." says Keasberry.

Ballast tanks, especially those located in the double bottom, generally speaking have limited access during the ship's service life. Repairs required because these tanks have rusted or corroded are usually expensive. However, using the right coating can mean that the tank may never need repair or repainting.

Even with uniformly standard products.

some coatings may perform better than others on various ships under certain unique conditions. To be certain that a customer can get exactly the coating that has been proven to work best, the coatings have been "fingerprinted" by a laboratory.

Sigma's general marketing manager Paul Cain explains: "Of course we were happy to agree to this fingerprinting.

When an owner has invested time, effort and money in a project it is understandable that he wants to be sure he is getting exactly the coating he has carefully chosen." Too much paint is as bad as too little.

A thin coat won't properly bond with the base surface, nor will it protect it.

Conversely, a thick coat will crack and expose the surface to corrosion.

In new construction, the total purchase cost of the coating is a small percentage of the total vessel cost, typically in the region of one-and-a-half to two percent but this increases to 8-10 percent when the costs of surface preparation and coating application are included.

Furthermore, says Cain, painting a new ship is time intensive, typically be in the region of 15-20 percent of the total time required to complete the vessel, which includes the entire coating process of application, surface preparation and inspection. "Using quick drying paints such as SigmaPrime can significantly boost production speed at newbuilding yards." The fewer types of primers and paints, the faster and cheaper it is to complete a vessel.

"Coatings have traditionally been a major bottleneck in the new construction of vessels. It's been calculated that when this process of using one primer for the entire vessel has been fully (and optimally) adopted, savings of up to two percent of total vessel value can be made," says Keasberry.

Giving the Slip to Marine Life In the last century, the maritime industry discovered that anti-fouling coatings could prevent the buildup of marine life on ship hulls. Such marine life like barnacles and algae, slowed the ship and clogged suction intakes and overboard discharges, and required periodic drydocking for hull cleaning. For similar reasons, power plants and other industrial applications used anti-fouling paints to keep intakes and discharges clear from marine life buildup. In the North American Great lakes, for example, the introduction of the invasive zebra mussels has caused extensive damage to shipping and industry due to the clogging of pipes and the resulting reduced efficiencies. A hull covered by marine life may consume up to 30 percent more fuel to cover the same distance in the same time.

Most of these anti-fouling paints contained biocides, or compounds that leached out of the paint to deter the growth of marine life. One of the main ingredients in such coatings has been tin in the form of Tributyl Tin Salts (TBT).

While TBT worked well, it was found to cause deformities in oysters and other shellfish. Further investigation showed that TBT was toxic, and subsequent regulations and legislation have virtually and universally banned TBT. The shipping industry understood and accepted the ban, but still had a need for an antifouling paint.

Marine plants and organisms need a surface to adhere to, so it stands to reason that it would be more difficult for marine life to bond to a very smooth surface.

The advantages to a hull that is free of marine life, and ultra-smooth and slippery, are obvious. Ships can get more speed for the horsepower, and use less fuel and horsepower to achieve speeds.

The disadvantages are a relatively high initial cost, and the fact that as a system, one or more sub coats of anti-corrosive coatings must be applied first. Brown says the elastomer coating is environmentally friendly, efficient and economical.

Capi. Edward Lundquist, U. S. Navy (Ret.), is communications director for the Center for Security Strategies and Operations for the Anteon Corporation in Arlington, Va.

Read Bottom Line: It's Not Just A Paint Job in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of August 2003 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from August 2003 issue

Content

- Letters page: 9

- Admiral Loy, Grace Allen Receive Silver Bell Honors page: 10

- Carrier for a New Energy Source page: 11

- Exhaust System Could Be Expanded to Entire Fleet page: 11

- Bollinger Delivers Supply Boat to Seacor page: 12

- Confused Seas page: 14

- Concordia Again Leads Tanker Innovation page: 16

- Intermarine Launches G5 Oltramonti page: 17

- Bottom Line: It's Not Just A Paint Job page: 18

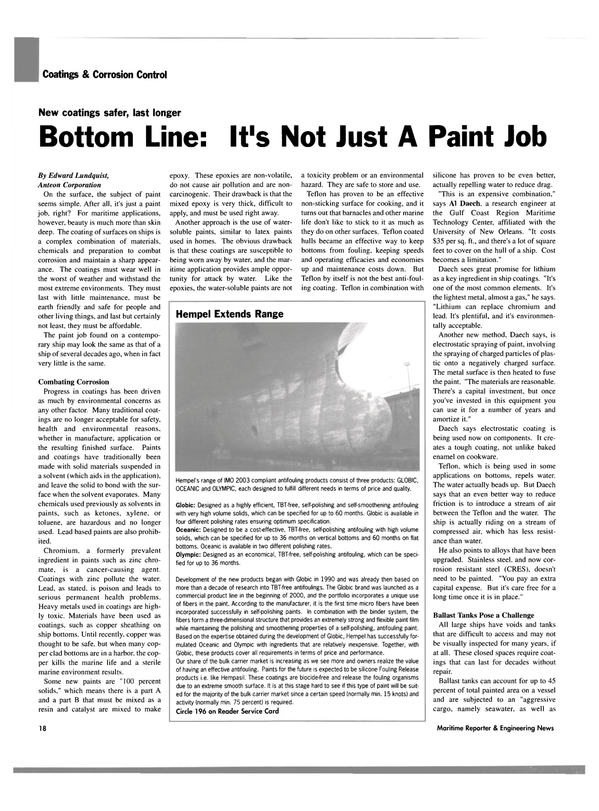

- Hempel Extends Range page: 18

- Nichols Bros. Launch Sternwheeler Cruise Ship page: 23

- Keppel to Deliver Maersk Rig Early page: 23

- Evergreen Orders 10 Post-Panamax Containerships page: 24

- USS Ronald Reagan Commissioned page: 25

- Littoral Combat Ship: It's Down to 3 page: 26

- Manitowoc, Kvichak Team for USCG Boats page: 29

- MV Manukai Christened at Philly Shipyard page: 30

- Emergency Sends S.S. Matsonia to Pearl Harbor Yard page: 30

- SENESCO Provides Major Facelift for NOAA page: 31

- Northrop Grumman Christens San Antonio page: 31

- Power to the Surveyor page: 32

- Wartsila: A Fountain of Ideas page: 33

- What Should be the Role of Class? page: 34

- RIB Report Northwind's Enforcer Provides Special Services page: 38

- Rough Water "New RIB on the Block" page: 40

- Salvors Forge Their Way into the Future page: 42

- Geislinger Delivers Record Sized Coupling page: 51

- Alstom Alspa Drive Fitted on Reasearch Vessel page: 51

- DNV's Five Points Fight Substandard Ships page: 55

- Strength Through Unity page: 55