Outlook for Floating Production Systems

Floating production has evolved to a mature technology that opens for development oil and gas reservoirs that would be otherwise impossible or uneconomic to tap. The technology enables production far beyond the depth constraints of fixed platforms, generally considered to be 1,400 ft. (426.7 m), and provides a flexible solution for developing shortlived fields with marginal reserves and fields in remote locations where installation of a fixed facility would be difficult.

Types of Floaters Floating production systems vary greatly in appearance - from ship-shape FPSO vessels to multi hull production semis to cylindrical shaped production spars. But common to all is machinery and equipment to lift oil and gas from seabed wells and perform initial processing of the raw production. Here's a rundown of the systems in operation.

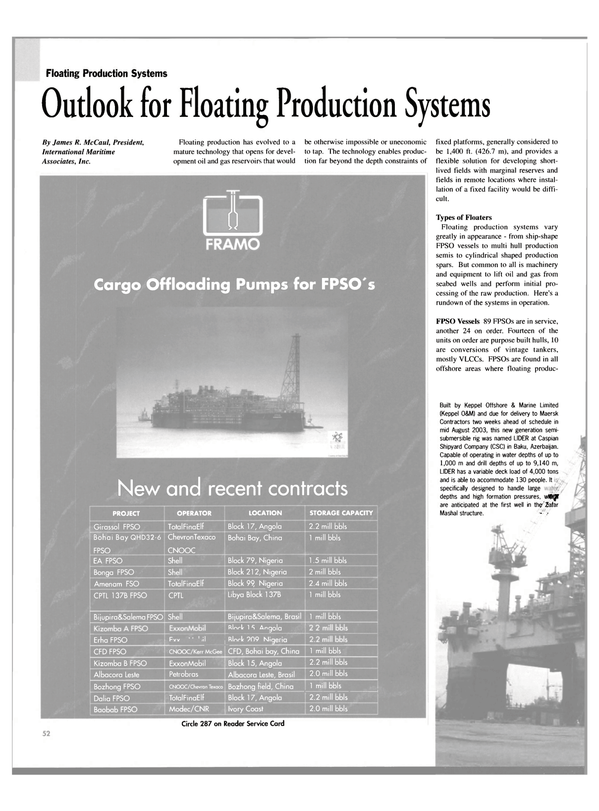

FPSO Vessels 89 FPSOs are in service, another 24 on order. Fourteen of the units on order are purpose built hulls, 10 are conversions of vintage tankers, mostly VLCCs. FPSOs are found in all offshore areas where floating produc- tion is used — with the notable exception of the Gulf of Mexico where FPSOs have still not been employed. The largest presence of FPSOs is in the North Sea and off Africa. Nineteen units are now operating in each area. They range in size from 50,000 bbl tankers with capability to process 10,000 to 15,000 b/d - to VLCC size units able to process more than 200,000 b/d and store two million barrels (e.g., the Bonga FPSO off Nigeria will be able to produce 225,000 b/d).

Some are held in place with a simple spread mooring system; some are fitted with a turret system that allows the vessel to weathervane. A few small units are held in place by dynamic positioning.

The choice of mooring system depends on local weather and sea conditions.

As many as 60 to 70 subsea wells can be tied back to the production unit (e.g., Dalia FPSO off Angola will be tied to 67 wells through nine manifolds) or the unit could be producing from only one well. Off-take and delivery of oil is accomplished using shuttle tankers, typically using tandem stern loading on weathervaning units and transfer via CALM buoy on spread moored units, with tandem loading usually provided as backup.

Cost of FPSOs varies greatly. Capital expenditure for a high production purpose built FPSO for a large field offshore Africa can exceed $700 million, with the hull costing $100 to 120 million, the topsides $500 to 600 million.

The Girassol FPSO, now operating off Angola, cost $756 million. The hull cost $150 million, topsides $520 million and project management and delivery comprised the balance. A more recent project, the Erha FPSO being built for offshore Nigeria, carries a total contract price of $700 million, with the hull costing $110 million, topsides and delivery the balance. At the other extreme, an FPSO for a marginal field utilizing a second hand tanker and fitted with a 50,000 b/d plant could entail a capex of one-tenth this amount. The operator of the Okwori field off Nigeria is planning to use an FPSO for production, but only if total capex for development is within $120 million. An FPSO operating offshore Libya since 2001 began producing on the field for a capital expenditure of $55 million, with conversion and topsides plant installation done at Malta Drydocks. Hull and topsides contracts are sometimes awarded separately, sometimes awarded as a single contract.

Sometimes the bidders are given the choice of taking the whole thing or just a portion. The upcoming competition for the Akpo FPSO contract will divide work into three packages — hull, topsides and project management — and bidders will have the choice of bidding one, two or three work packages.

FPSO fabrication and conversion contracts have become the province of Asian yards. Samsung and Hyundai are the big players in high end FPSO fabrication (e.g., units for Kizomba, Dalia, White Rose, etc). Dalian and Shanghai Waigaoqiao have been making inroads on low-end projects (e.g., Belanak, Caofeidian, Panyu FPSOs). Almost all recent FPSO conversion work has been captured by Keppel, Jurong, Dubai Drydocks and MSE.

Production Semis 38 production semis are in service, with three more on order.

Brazil, where the concept of using converted drill semis for production originated, accounts for 19 of the units now in service. The North Sea is the other area where a large number of production semis are in service, with 12 units now operating. Until now there has been little use of production semis in the Gulf of Mexico. An early version, Garden Banks, was removed from operation several years ago. But this production concept has again found appeal among Gulf field operators. A production semi (Nakika) is now being installed in the Gulf and two more (Atlantis and Thunder Horse) will begin operating in the Gulf within the next two years.

Production semis vary greatly in size and complexity. Some older units offshore Brazil, Africa and Southeast Asia have capability to produce only 10,000 to 25.000 b/d of oil. At the other extreme, the Thunder Horse production semi will have processing capacity for 250,000 b/d and an existing unit in the North Sea, the Asgard B, can produce 130.000 b/d condensate and 1,300 MMcf/d gas.

Some of the larger systems have tie backs from more than 20 wells.

Thunder Horse will be tied, initially, to 25 wells. As there is no storage on the production unit, either a separate floating storage unit is employed on the field for storage and offloading or pipeline off-take direct to shore is utilized. Most production semis utilize the latter.

Because of motion at the surface, well control devices are fitted at the ocean floor and fluids are brought to the sur- face via flexible or steel risers.

However, Shell's new Nakika production semi in the Gulf of Mexico will utilize dry trees for some wells - i.e., well control devices will be on the topsides for easy maintenance. The days of taking a surplus drill rig and converting it at minimal cost to a production semi are gone. Now that candidate surplus hulls are no longer available, the units now being built are rather costly. A purpose built production semi intended for use on a complex field will cost $500 to 900 million, depending on the plant capacity and gas producing capability. The Kristin production semi, now being built for use off Norway, entails capital expenditure of $860 million for hull and topsides. The Thunder Horse semi hull is a $300 million fabrication job, while the hull and topsides for Nakika cost $600 to 650 million. Three major Korean yards are the big players in this sector. Hyundai had entire contacting responsibility on the Nakika production semi. Daewoo is building the hulls for the Thunder Horse and Atlantis semis, with McDermott supplying the topsides.

Samsung is fabricating the Kristin production semi hull, and Aker Stord is supplying the topsides.

Production Spars Seven production spars are in service, six on order - all in the Gulf of Mexico. This type of production system has not found favor else- where, at least to date. These are purpose built cylindrical shape units supporting a topside deck fitted with capability to process 25,000 to 100,000 b/d.

The largest unit is ExxonMobil's Hoover/Diana spar, which has ability to produce 100,000 b/d oil and 325 MMcf/d gas. The smallest unit is Neptune, the original spar deployed in the Gulf of Mexico in 1997, which can process 25,000 b/d. A new unit under construction. Red Hawk, is a small spar designed for gas production.

Weight bearing capability is less than the previous two production systems and spars would generally be used on mid-size fields. Storage could be provided in the hull - but spars built to date have no storage. Spars are widely used in the Gulf of Mexico, as pipeline infrastructure in the Gulf to date has eliminated the need for storage on the field.

Also, spars are stable platforms that allow well control devices to be placed on the topsides. Operators in the Gulf find this to be of importance as it reduces maintenance costs associated with high paraffin oil.

A heavy deckload spar such as Hoover/Diana will entail a capital expenditure of $300 to 500 million.

Smaller spars such as Devils Tower will have a capex in the $200 million area.

Light deckload spars such as Red Hawk will cost in the $100 million area.

Hull cylinder fabrication has been largely the province of Technip, using its facility in Finland. Hulls for six of the seven spars in service have been fabricated in Finland and three more are on order there. But McDermott has taken three spar hull contracts using the company's fabrication facilities in the UAE and Indonesia, a venture that has not worked out too well, and a recent order for a small spar hull went to Gulf Marine in Texas. Spar topsides fabrication has been almost totally the province of McDermott.

Tension Leg Platforms TLPs come in three variations — large deckload, mini and wellhead. Altogether, there are 15 TLPs in service (nine full size, five minis, one wellhead) and four on order (two minis, two wellhead). The original full size version is a large expensive unit capable of supporting a high throughput processing plant. The Snorre TLP, operating in the North Sea, holds the current TLP plant capacity record, with capability to process 190,000 b/d oil and 113 MMcf/d gas). Two full size TLPs are operating in the North Sea, seven in the Gulf of Mexico. Because heave motion of the floater is restrained by tendon tension, well control devices can be installed on the topsides, making maintenance easier. The ability to use dry trees has historically been a major reason for choosing this type production system. But full size TLPs have fallen out of favor due to their high cost and inability to be used in very deep water.

Tendon weight becomes a major issue as the water depth increases beyond 1,200 m.

Now interest has shifted to mini-TLPs designed for mid-size deepwater fields.

They are smaller, lighter and able to support a processing plant up to 50,000 to 60,000 b/d. But unlike their big brothers, they are able to be used in very deep water. The Magnolia mini-TLP, now on order, will be placed in 4,691 ft. (1,430 m) water depth. Modec and IHC Caland are marketing mini-TLP designs, five of which have been installed and two more are on order.

Using TLPs as wellhead platforms has also recently gained favor. The TLP is fitted with machinery to control well production and the oil processing plant is placed on an accompanying production unit. ExxonMobil is utilizing a combination wellhead/FPSO production system on its massive Kizomba A and B developments offshore Angola. A smaller wellhead TLP/production barge combination is now being installed on the West Seno field off Indonesia.

Capex for a large wellhead TLP will likely be in the range of $500 to 600 million.

The Kizomba A wellhead TLP cost $650 million, but this is an exceptionally large and complex field and the cost will probably come down as additional units are built. Capex for a small wellhead TLP will likely be in the range of $80 to 100 million. The West Seno wellhead TLP/production barge combination cost $265 million, of which the TLP probably accounted for two-thirds.

Mini-TLPs cost about $150 to 250 million.

depending on the capacity of the production facility placed on deck.

Samsung and Daewoo are the big players in TLP hull fabrication.

Samsung is fabricating the Marco Polo and Magnolia hulls, Daewoo has the contract to supply the wellhead TLPs for Kizomba A and B. Hyundai is also in this market, having fabricated the small wellhead TLP for West Seno and is in line for the second unit on this field.

This is a lot different than the old days, when Belleli basically controlled TLP hull fabrication. Topsides fabrication for Gulf of Mexico units has been going to McDermott, Gulf Marine or Kiewit Offshore. ABB/Heerema has a role in topsides engineering and fabrication for the wellhead TLPs off Africa.

Future Floater Orders In a recent study, we identified 94 offshore projects that have strong likelihood to utilize a floating production system should they move to the production stage. West Africa is the clear leader in terms of potential projects, with 12 projects in the bidding or final design stage and anather 14 in the planning phase. The Gulf of Mexico is second, with 17 projects planned or under study. In third place is Brazil with 15 projects, followed by Southeast Asia with 12, Australia with eight and Northern Europe with six projects.

Based on our analysis of projects being planned, we see a requirement for 245 to 270 floating production systems by the end of the decade. Taking into account: the number of units currently in operation, the number of units now on order, and the likely scrapping and loss rate, we see a need to order 62 to 89 additional floaters over the next five years to meet this requirement.

Of this total, we expect 60 percent will be FPSO vessels, 30 percent spars or TLPs and 10 percent production semis.

We also project that the mixture of floater orders will produce a capex value of $22 to 31 billion over the five year forecast period.

About InternationaI Maritime Associates International Maritime Associates (/MA) was formed in 1973 to provide strategic planning support to clients in the offshore oil and gas, maritime and technology sectors.

IMA performs the research needed to size the available market, analyze customer requirements, assess competitor strengths/vulnerabilities and evaluate options for optimizing market position. This article is taken from a new in-depth assessment by IMA of the outlook for FPSO vessels, production semis, TLPs and spars. The HO page report is the 19th in a series of in-depth analyses by IMA of this market sector that began in 1996.

Contact Jim MeCaul, Tel: 202-333-8501, email: [email protected], website: www. imastudies. com

Read Outlook for Floating Production Systems in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of September 2003 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from September 2003 issue

Content

- New SWATH From ACMA page: 8

- IZAR Delivers LNG Inigo Tapias page: 10

- Wallace McGeorge Modified for Deep Dredging page: 11

- Careful, Your Species May Be Non-Indigenous page: 12

- U.S. Sub Christened in "Home" Port page: 16

- HSV 2 Swift Delivered to U.S. Navy page: 17

- A Change in Course page: 18

- Univan Reports Steady Growth page: 20

- Payload Pivotal to Fast Sealift Ship page: 24

- The Chairman's Influence on Design page: 24

- The Lure of the Electric Drive page: 26

- Very Large Systems page: 27

- Generators And Synchronous Condensers page: 27

- Cat Power For Unique Boat page: 30

- MAN B&W Flexibility With Two Strokes page: 31

- "Ink" It In: WMTC a Must for Maritime Professionals page: 34

- Guido Perla: Colombian Born, American Made page: 38

- Thrane & Thrane Offers the Capsat Fleet33 page: 42

- SeaWave Family Designed for Ease of Use page: 42

- PGS Geophysical Renews With Telenor page: 43

- Nera F 5 5 Terminal Gets Inmarsat Type Approval page: 44

- Monitoring Technology...Advanced page: 45

- Outlook for Floating Production Systems page: 52

- Meyer Werft Delivers to RCCL page: 57